Sid Kaplan

Print: 10 x 8 inches

Signed by the artist on verso

Print: 10 x 8 inches INV Nbr. SK1910003 Kindly.

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed by the artist on verso

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK1910008 Kindly.

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed and titled by the artist on recto

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK1910010 Kindly.

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed and titled by the artist on recto

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK1910011 Kindly.

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed and titled by the artist on recto

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK1910012 Kindly.

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed and titled by the artist on recto

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK1910013 Kindly.

Image : 12.2 x 8.27 in ( 31,6 x 21 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 12.2 x 8.27 in ( 31,6 x 21 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2001005 Kindly.

Image : 8.27 x 12.6 in ( 21,2 x 32 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 8.27 x 12.6 in ( 21,2 x 32 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2001031 Kindly.

Image : 9.06 x 4.72 in ( 23,7 x 12,5 cm )

Print: 9-3/8 x 4-15/16 inches

Signed by the artist on verso

Image : 9.06 x 4.72 in ( 23,7 x 12,5 cm )

Print: 9-3/8 x 4-15/16 inches INV Nbr. SK2001046 Kindly.

Image : 13.78 x 13.78 in ( 35 x 35,5 cm )

Print: 20 x 16 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 13.78 x 13.78 in ( 35 x 35,5 cm )

Print: 20 x 16 inches INV Nbr. SK2003007 Kindly.

Image : 18.11 x 14.17 in ( 46,6 x 36,5 cm )

Print: 20 x 16 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 18.11 x 14.17 in ( 46,6 x 36,5 cm )

Print: 20 x 16 inches INV Nbr. SK2003008 Kindly.

Image : 11.81 x 7.87 in ( 30,8 x 20,8 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 11.81 x 7.87 in ( 30,8 x 20,8 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2003047 Kindly.

Image : 12.2 x 7.87 in ( 31,5 x 20,2 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist

Image : 12.2 x 7.87 in ( 31,5 x 20,2 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2003057 Kindly.

Image : 12.6 x 8.27 in ( 32,3 x 21,4 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed and titled by the artist on recto

Image : 12.6 x 8.27 in ( 32,3 x 21,4 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2003066 Kindly.

Image : 12.99 x 7.87 in ( 33 x 20,8 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 12.99 x 7.87 in ( 33 x 20,8 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2003060 Kindly.

Image : 9.84 x 9.84 in ( 25,4 x 25,4 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 9.84 x 9.84 in ( 25,4 x 25,4 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2003065 Kindly.

Image : 12.2in ( 31,3 x 20,5 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches

Signed, titled and dated by the artist on recto

Image : 12.2in ( 31,3 x 20,5 cm )

Print: 14 x 11 inches INV Nbr. SK2003061 Kindly.

Image : 9.84 x 9.84 in ( 25 x 25,3 cm )

Print: 10-3/16 x 10-5/16 inches

Signed, titled and dated with pencil by the artist on verso

Image : 9.84 x 9.84 in ( 25 x 25,3 cm )

Print: 10-3/16 x 10-5/16 inches INV Nbr. SK2003064 Kindly.

Presentation

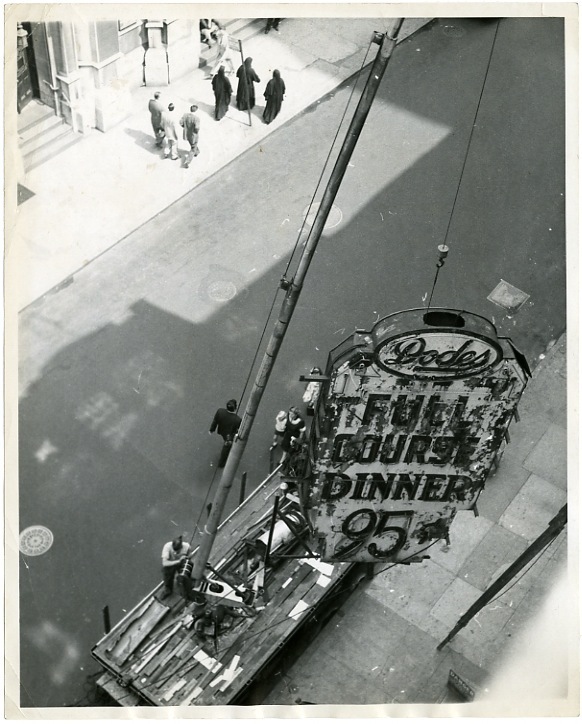

After graduating from The School of Industrial Arts, Sid worked from 1956 until 1962 at a series of nondescript minimumwage jobs in the photography industry. As Sid describes, “It was a perfect way to learn, to sharpen up and practice my craft and skills at someone else’s expense.” These years eventually led to a black-and-white printer’s position at Compo, the premiere custom lab in Manhattan.

At Compo, Sid printed for some of the greatest photographers of the last 50 years, including Philippe Halsmann, Robert Capa, Weegee, and most of the members of Magnum. In 1968 Sid left Compo to become an independent printer. “My life had become too much darkroom and not enough photography,” he decided. At 10 East 23 Street Sid built a darkroom and set up shop, printing “any- and everything that came through the door.” W. Eugene Smith occupied an adjacent loft for several years, and Ralston Crawford was a neighbor. Ralph Gibson introduced Sid to Robert Frank in 1969 and Sid became Frank’s printer, a relationship that lasted thirty-five years. Sid’s clientele grew to include Allen Ginsberg, who also became a neighbor when Sid relocated his darkroom to Avenue A in the East Village. Since 1972, Sid has been a faculty member of the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where he teaches black-and-white darkroom courses.

He has made more than 91,000 images, not counting the bad rolls of film he decided not to keep.

The Rose Library at Emory University, Atlanta, GA récently purchased Sid Kaplan’s negatives, contact sheets, and two copies of all of the images.

Press

Texts

Looking at Sid Kaplan’s images is a rare experience. For although the eighty-two-year-old New York photographer still has a studio and dark room in the East Village, he has seen his career effectively hidden by the bulky legend of Mr. Frank, as Kaplan calls the man whose photographs he printed for thirty-five years.

So it was that Robert Frank (1924-2019), author of the 1958 book, The Americans, published in France by Robert Delpire, acted as the tree that hides the forest. And despite him declaring that, ‘Sid Kaplan is not only an excellent printer, but also a very great photographer who is still too little known’, not much has changed. Kaplan would have to wait until 2005 for galleries to take an interest in his life’s work – some 96,000 images – and give it exposure and recognition.

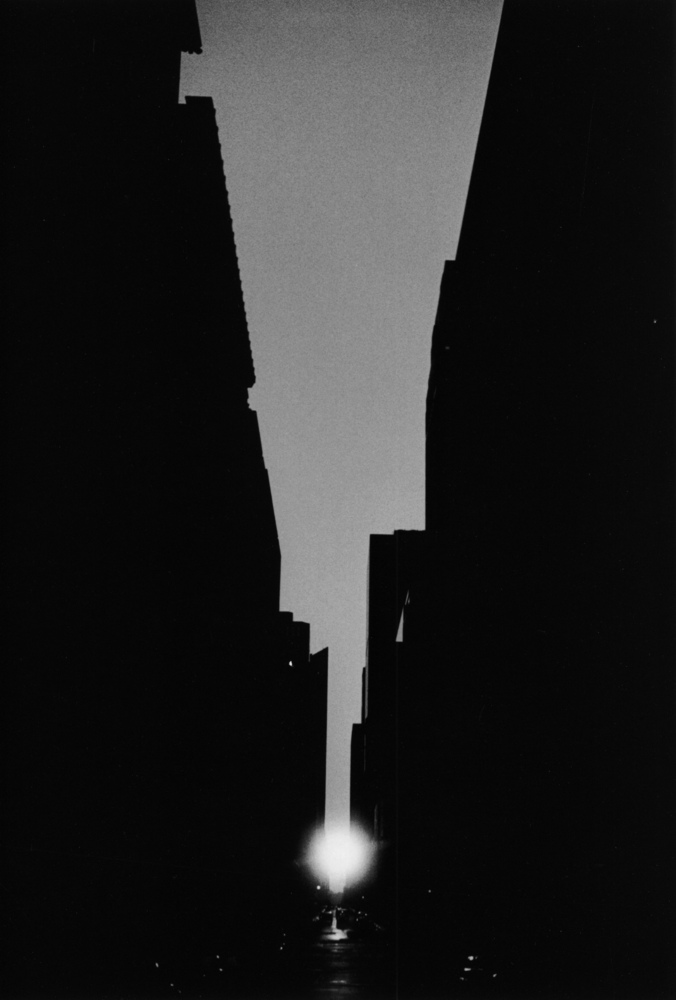

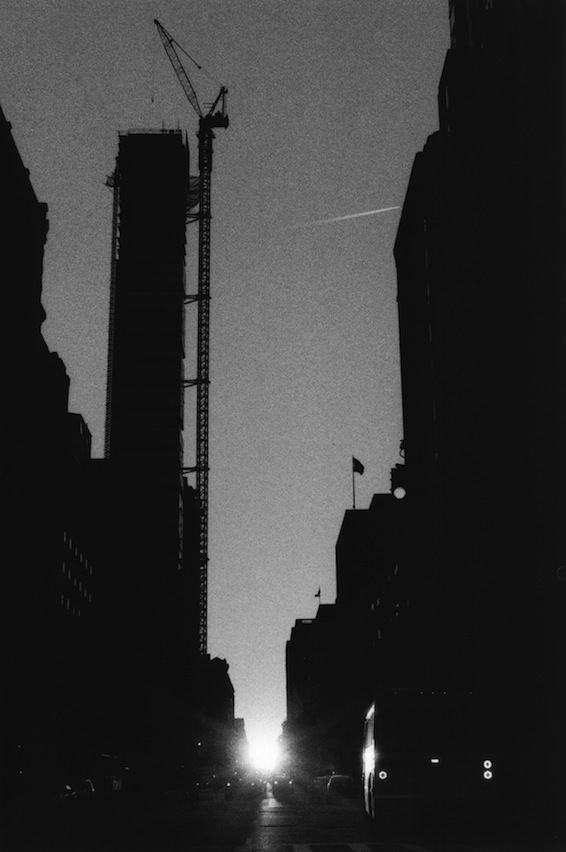

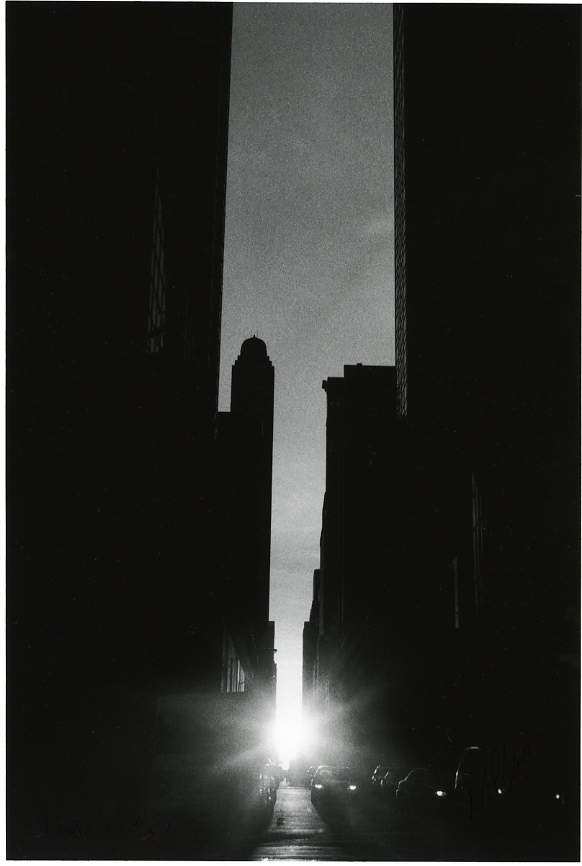

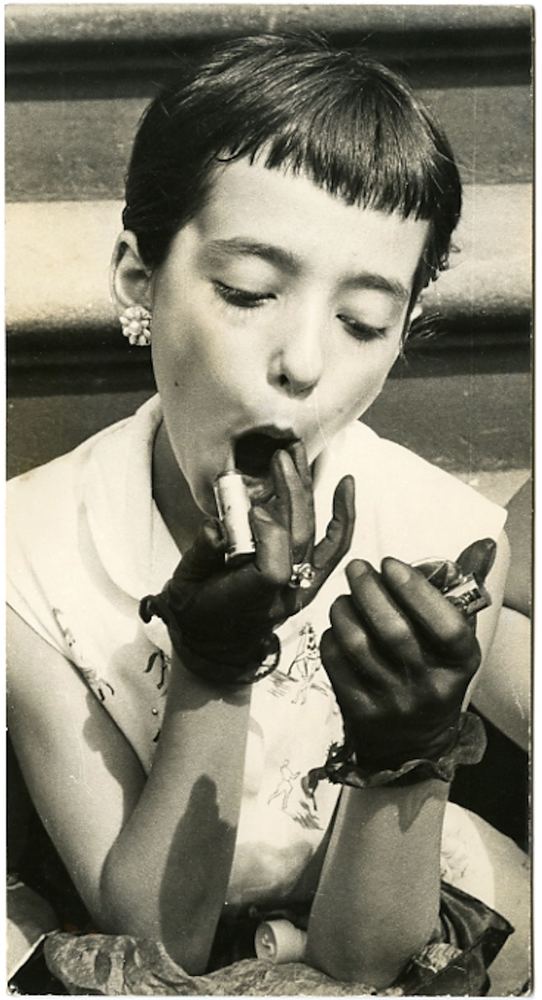

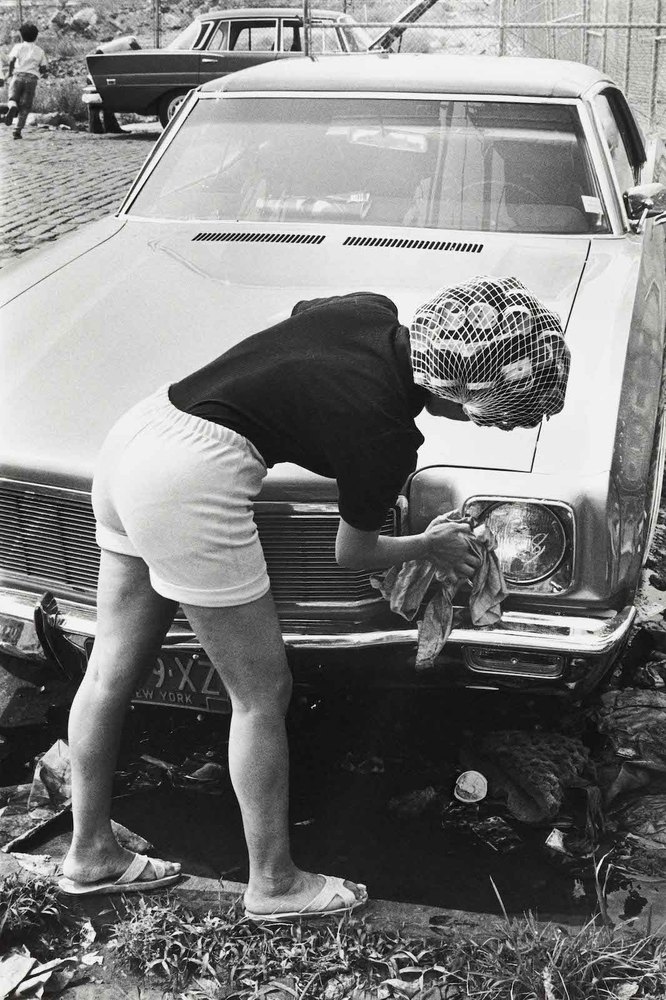

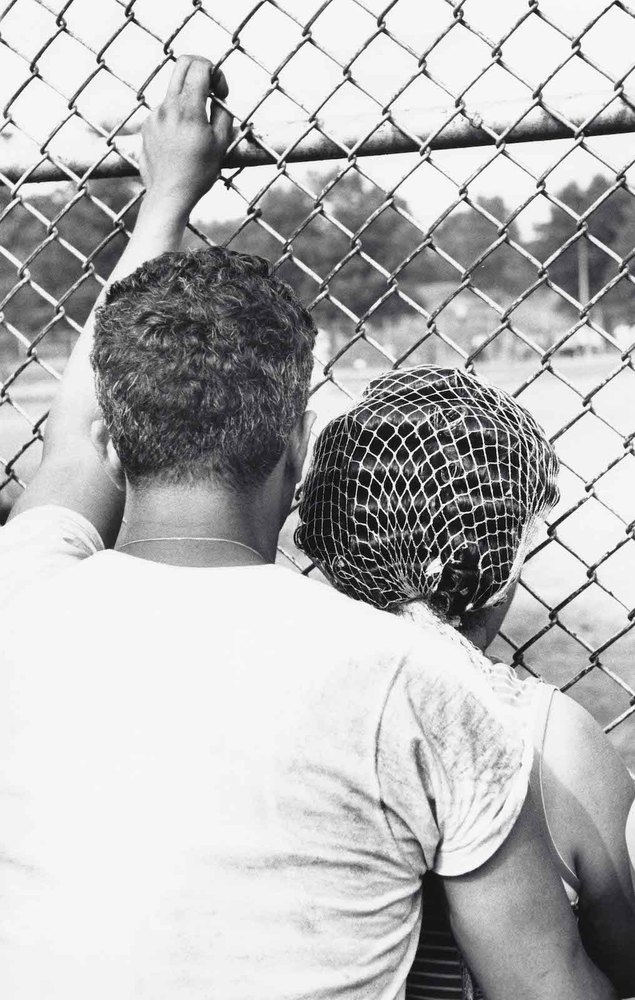

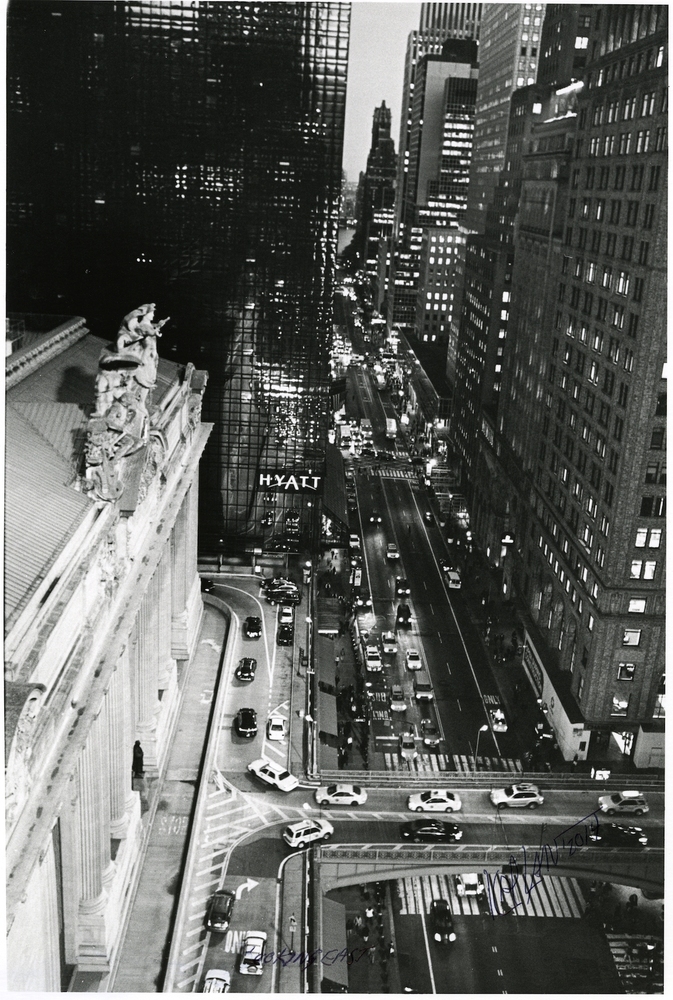

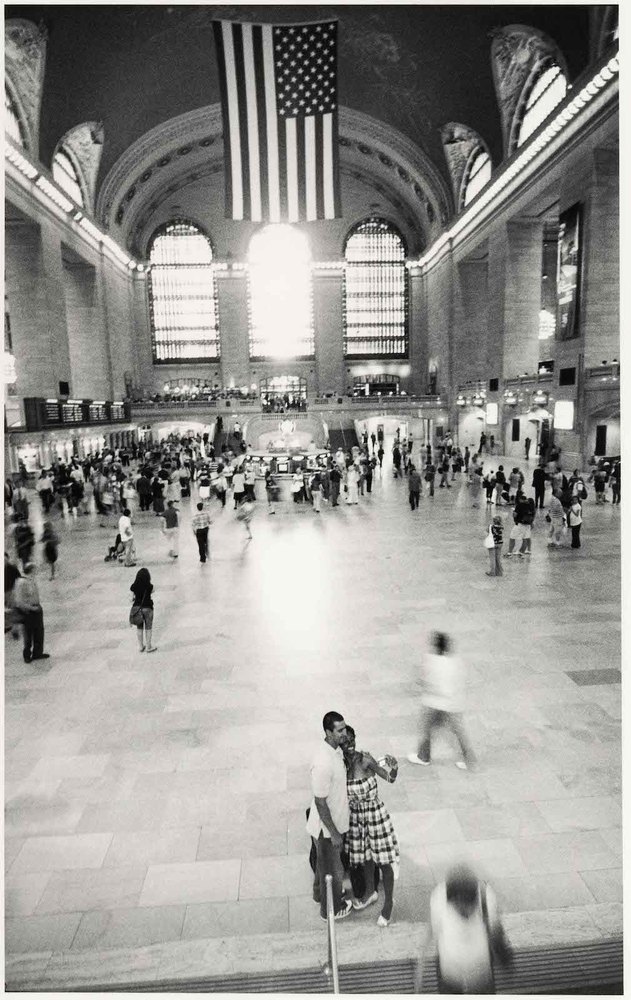

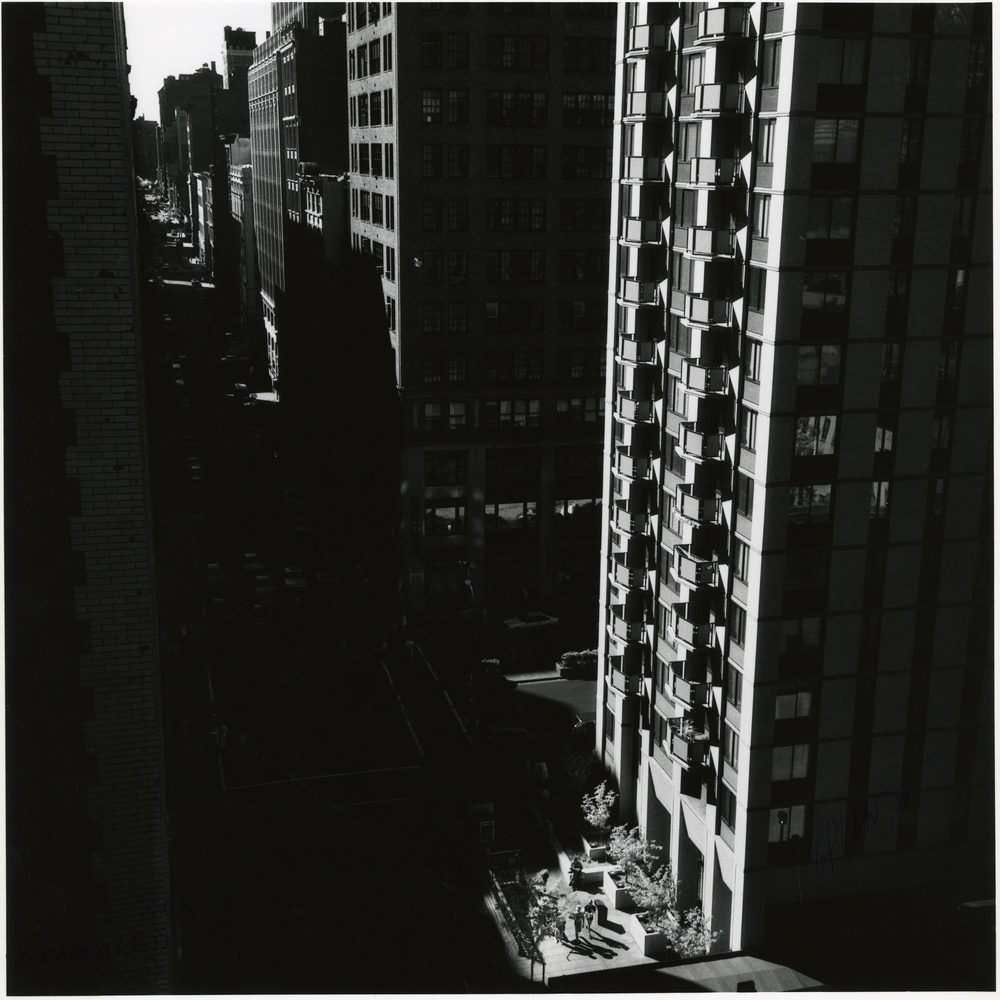

You’ll fall for the charm and energy of the celebrated American streets. How though? What guides Kaplan’s gaze as he hangs out in a New York bar and notices a smoker overlooked by three screens? Or when the snow has the same effect on him as when he was a kid, and he goes out all excited to capture the magic of the whitewashed urban landscapes? When for two years he photographs an intersection situated at the corner of Madison Avenue, looking from a window? When he stares at the sunset, for ten years, through Manhattan’s skyscrapers after the winter and summer solstices?

Kaplan is a far cry from Gary Winogrand and his frenetic shooting, which captured not only women, but while he could, the energy and flux of the urban bazaar. Far from Lee Friedlander who, as a disciple of Walker Evans, tried to bring to life a social landscape. Far from Louis Faurer who favoured the fragility and doubt of the anonymous people he met, often at night. From Diane Arbus whose portraits reveal the devil hiding in each of us.

Sid Kaplan is not in a rush to snap photos; he’s not looking for the golden mean. As he explained to his gallerist Deborah Bell, ‘For me, the best way of practicing photography is to do it in my free time, like Jacques-Henri Lartigue or Alfred Stieglitz. I never wanted to have a job that put me at the mercy of artistic directors and deadlines. That would have driven me crazy.’ To his colleague, the French printer Guillaume Geneste, who wrote the book Le tirage à mains nues [Bare-handed Printing], which was recently published by Éditions lamaindonne, he maintained that, ‘I knew I didn’t want to be in a studio. I just wanted to be alone with my camera and walk around, taking my own photos.’

When and where did his desire for photography originate? In the south Bronx where his Jewish family from Eastern Europe had taken refuge. Then, at the age of fourteen, chance would have it that he met Weegee. That’s when he said he became ‘hypnotised, drawn as if to a drug’ when for the first time he discovered an image taking shape in the developing tank.

Eugene Smith became his neighbour. Ralph Gibson introduced him to Robert Frank, ‘a paying client’. Meanwhile, having to earn a living, the young man began working for Compo, Manhattan’s most prestigious photography lab. There he spent his life in the dark room. But through washing, glazing, drying the prints, his eye continued to develop.

While at Compo, he hobnobbed with the most sought-after photographers of the time, including the contributors to The Family of Man exhibition, which spread across the whole world, the FSA (Farm Security Administration) team, photographers at the Magnum agency, including Cornell Capa, who had him print his brother Robert’s photos, and Lou Bernstein at ICP, Philippe Halsman, the poet Allen Ginsberg, and the list goes on…

A number of the photographers were very active in The Photo League, which eventually fell victim to McCarthyism, leading to its dissolution. They were reporters and photojournalists with not only artistic concerns, but social ones as well. They wanted to bear witness. Not true of Sid Kaplan. Growing up in the Bronx, he certainly new poverty, he is certainly steeped in the Jewish culture of Eastern Europe, and he barely ever leaves the Lower East Side, but he doesn’t in the slightest feel as though he has a mission. Except maybe to transmit his fantastic know-how as a black-and-white printer to New York’s School of Visual Arts, where he teaches.

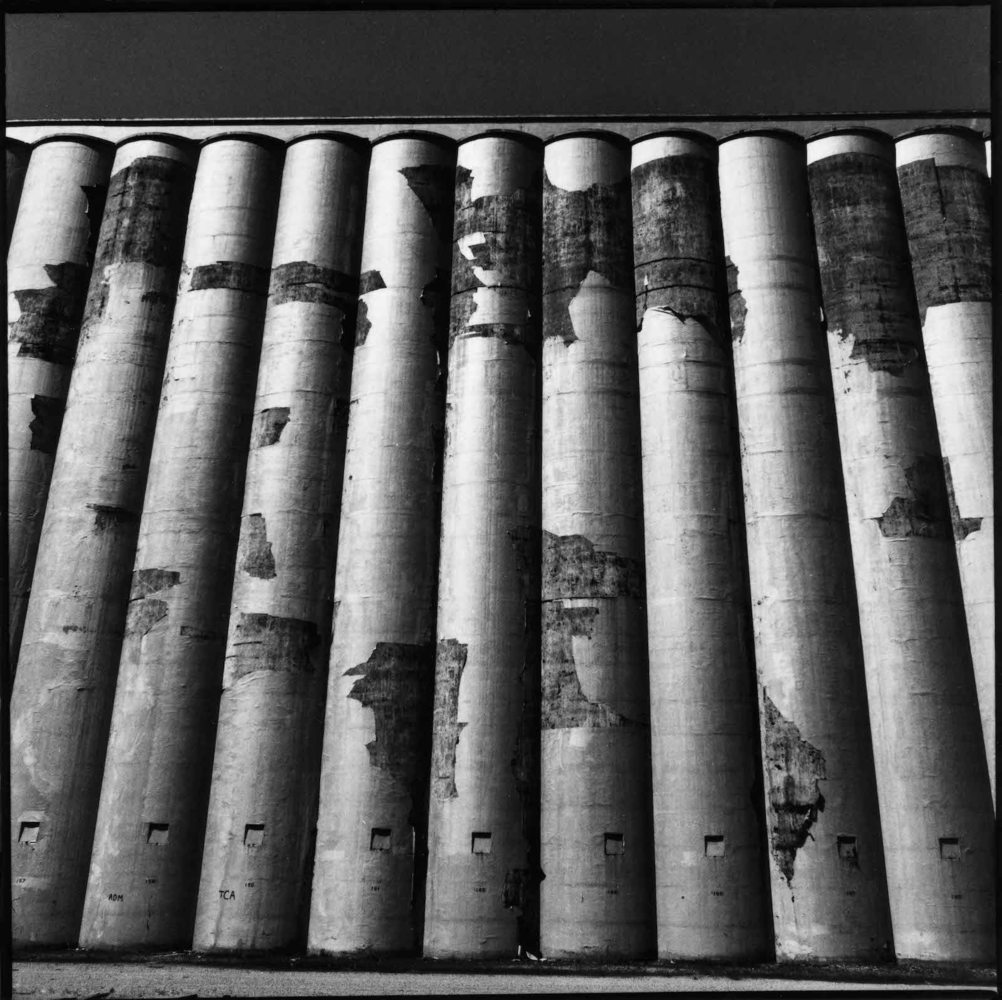

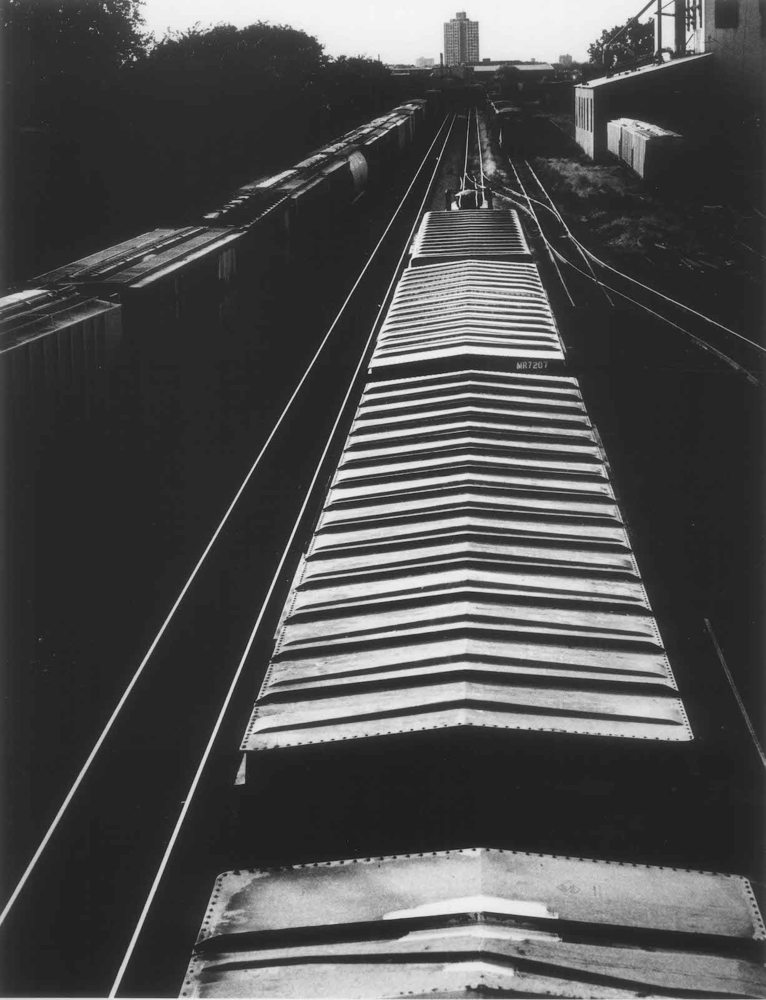

Lines in space, high luminosity, traces of a long-gone New York, a street scene with kids, a passing cloud… Sid Kaplan the documentarist humbly relishes what would have thrilled André Kertész. The human doesn’t interest him all that much. He can’t be bothered. But most of all, nothing is off-limits for him. He isn’t afraid of being eclectic, which in him has a force that keeps him far, very far indeed, from the anecdotal.

Magali Jauffret

Art Critic