La couleur a toute epreuve

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Frame: 24 x 31 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Image: 17 x 26 inches

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Frame: 24 x 31 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Frame: 24 x 31 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 30 x 40 inches

Frame: 30 x 40 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Frame: 24 x 31 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Frame: 24 x 31 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 18 X 24 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 30 x 40 inches

Frame: 30 x 40 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 cm

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Frame: 24 x 31 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 30 x 40 inches

Frame: 30 x 40 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Image: 17 x 26 inches

Print: 20 x 30 inches

Frame: 24 x 31 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 30 x 40 inches

Frame: 30 x 40 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 2à x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 20 x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

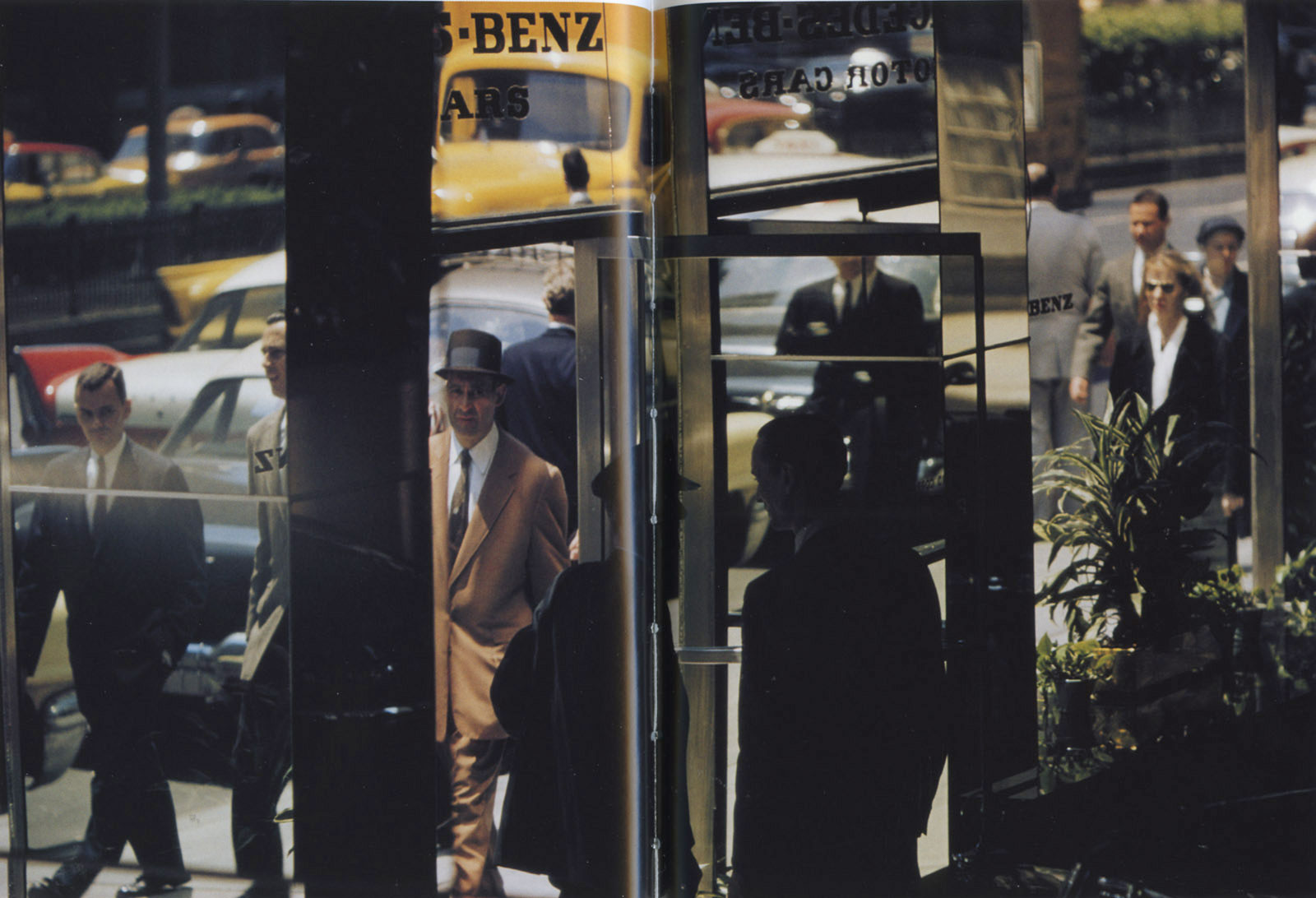

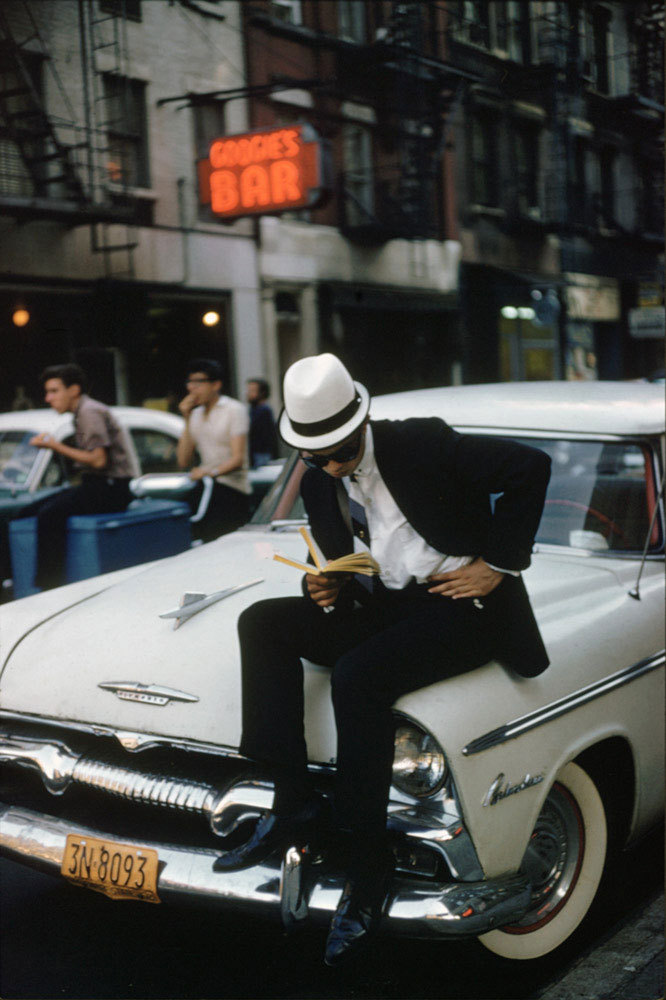

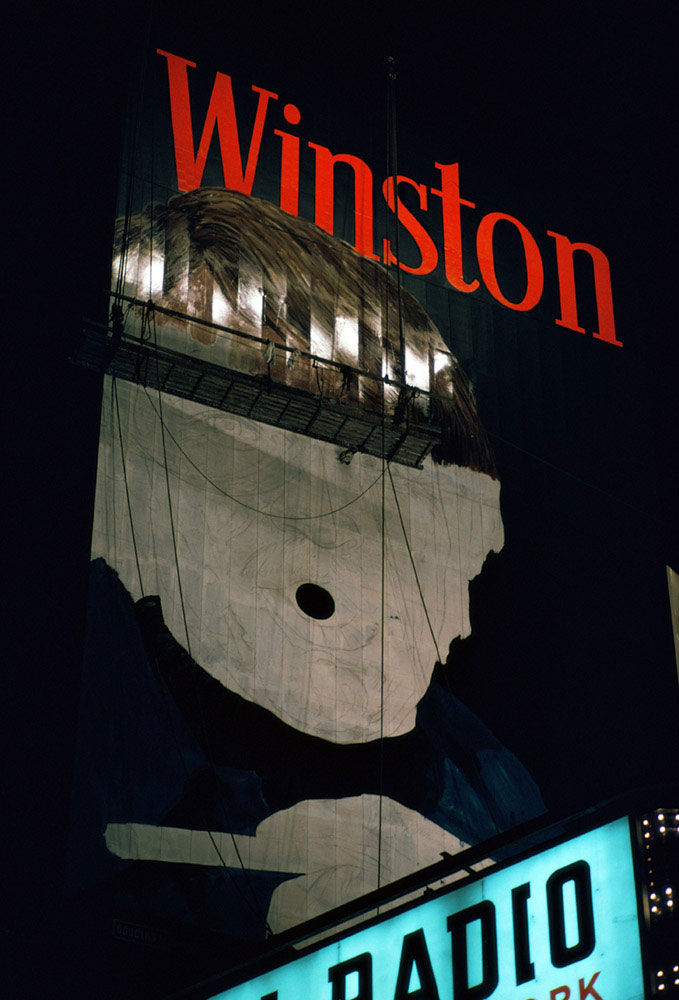

Presentation

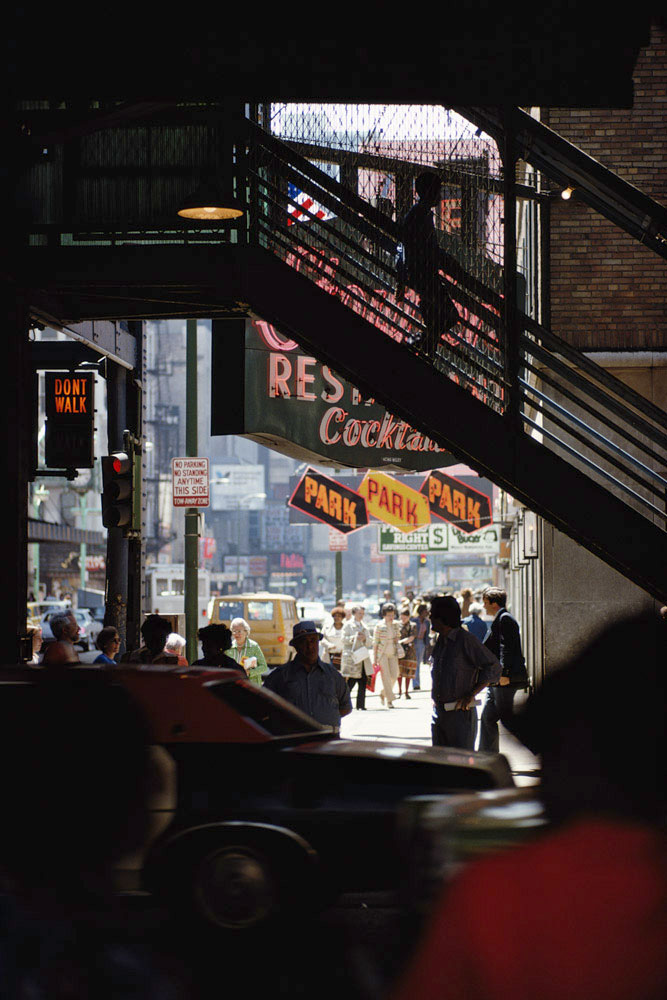

Living as we do in the digital age, it is difficult for us to imagine the number of photographers who found their calling after discovering the work of Ernst Haas. His publications and his retrospective at the MoMA in 1962 have influenced an entire generation. We?ve forgotten now, but colour film was difficult to handle. It was light years ago, in 1952, when the American magazine Life asked him use colour to work on the city of New York. Capa, at Magnum, was the only person who understood why he wanted to experiment with colour. After all, black and white was still king. But Ernst Haas was unperturbed. In order to understand his highly singular adventure, we must see it in its historical context. Born in 1921 to a family of Jewish origins, Haas lived through the trauma of the Second World War. Subsequently, in 1951, he emigrated to the United States, a country he had dreamed of since his youth. He was an optimistic man, with no professional strategy, for he himself had never asked anything of anyone. He was a free man.

Press

PRESS RELEASE

Ernst Haas was unquestionably one of the best known, most prolific, and most widely published photographers of the twentieth century. He is commonly associated with a vibrant color photography which, from the 1950s on, was much in demand by the illustrated press. This work, published by dozens of influential magazines in Europe and America, also fed a constant stream of book projects. These too, enjoyed great popularity.

But although Haas?s color work earned him fame around the world, decade after decade, in recent years it has been derided by critics and curators for the very characteristics that made it so popular with magazine editors ? its immediacy and accessibility. In a nutshell, Haas has been criticized for being ?too commercial?, a sin in a field where every effort had (and has!) to be made to distance the supposedly fragile art form from contamination with crassly commercial endeavors. His work was also judged too simplistic, lacking in the complexities and ironies that marked the imagery of Haas?s younger rivals, who were also busy forging a new language color. As a result, Haas? reputation has suffered in comparison with the leading lights of what came to be known as ?the New Color?, notably William Eggleston, Joel Sternfeld, Stephen Shore, and Joel Meyerowitz.

Paradoxically, however, there was another side to Haas?s work, an aspect that has escaped posthumous appreciation. This side shows him to be by no means inferior to his younger colleagues in innovation. For, parallel to his commissioned work, Haas constantly took pictures for his own pleasure, and as far as I can make out, without any particular intention to share them with others. These pictures show a very different aspect of his sensibility ? they are far more edgy, loose, enigmatic, and ambiguous than his celebrated work. Most of these pictures he never even printed, let alone published, probably assuming that they were too difficult to be understood. These images are of great sophistication, and rival (and sometimes surpass) the best work of his colleagues (...).

It is one of those ironies in life that the distinguished curator, John Szarkowski, who exhibited Haas early on but then decided not to champion him, led me indirectly to the photographer?s hidden work. Like other young curators of my generation, I had also dismissed Haas?s work for the reasons stated above, as well as for what I considered an excessive sentimentality. And yet one of his color photographs gnawed away at me over the years, resisting this dismissive appraisal. It was a picture that Szarkoswski had once reproduced in a Museum of Modern Art publication ? a street scene with awnings and their reflections which could not help but evoke a Morris Louis painting. The billowing color of the awning rippled like flames, and I recalled the old adage, ?where there?s smoke, there?s fire?. There had to be more where this came from! Then, many years later, as I was re-reading Szarkowski?s thoughts on color, I was amused to find another appropriate metaphor. ?As recently as the 1960s,? he wrote, ?perhaps only Eliot Porter and Ernst Haas, among photographers then prominent, would carry from the proverbial burning house their color work before their black and white.? A dormant seed stirred in my mind.

Around 2006, I mentioned my thoughts to fellow curator Graham Howe, and found that he, too, had similar suspicions. We resolved to go to the Haas archive in London, and see if our instincts proved sound. We made a first foray, and decided that, indeed, there were smoldering embers which with a little oxygen might burst into flame. Although I went on to do the research alone, for practical reasons, over the next couple of years I managed to go through all 200,000 color slides ? partly driven by the sheer visual excitement, and partly to assure myself that I wasn?t ?making up? this shadow Haas. I do not believe I was, and the imagery in this book is my best argument.

William Ewing

Curator and author

Introduction of Ernst Haas Color Correction, published by Steidl in 2011