Une fantastique passion

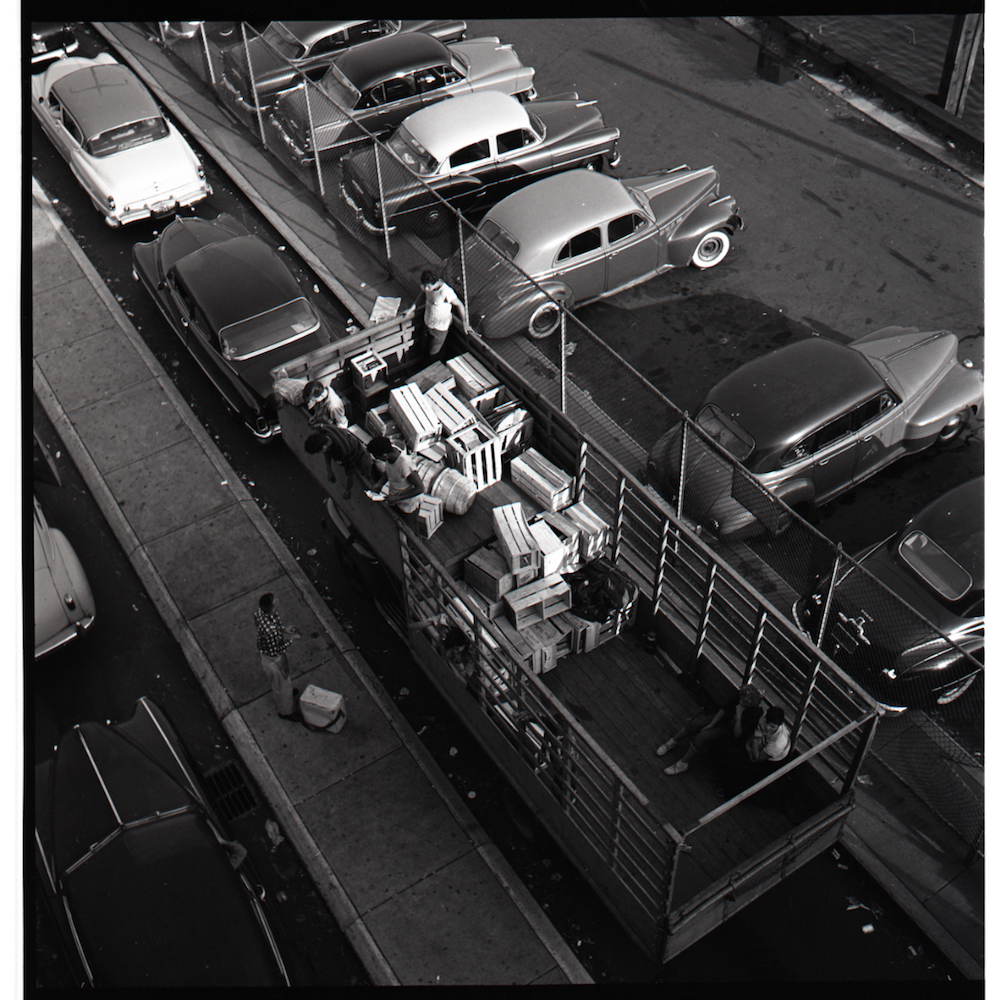

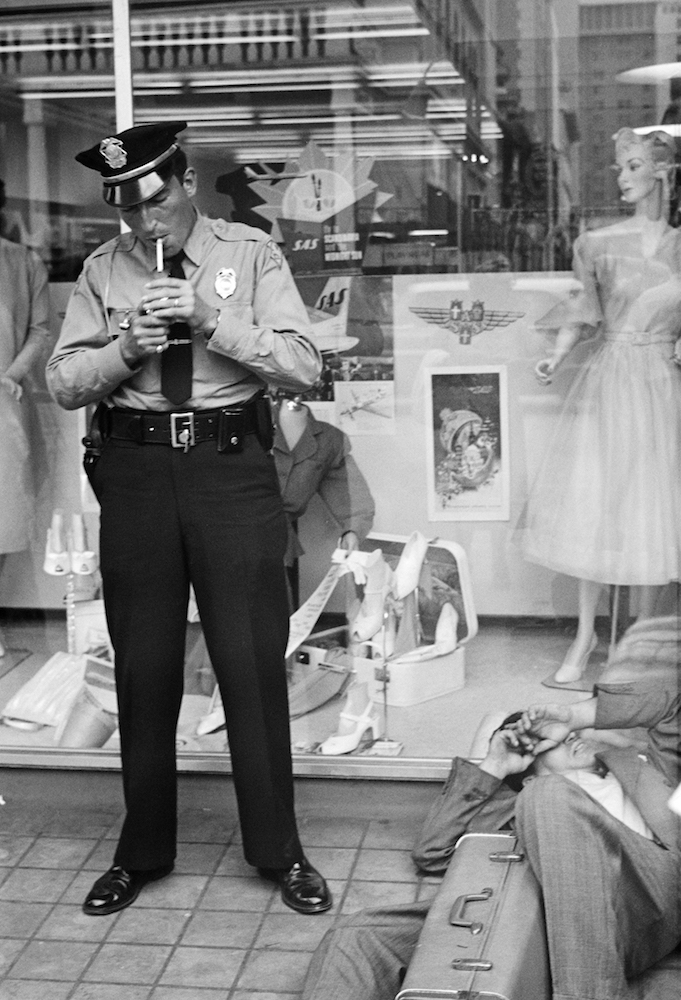

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

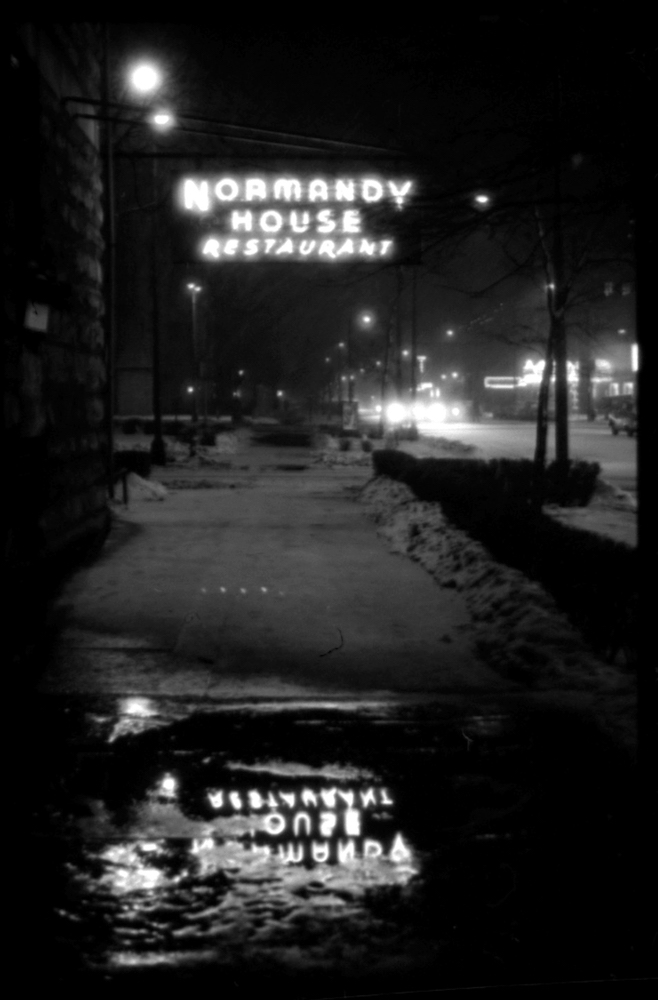

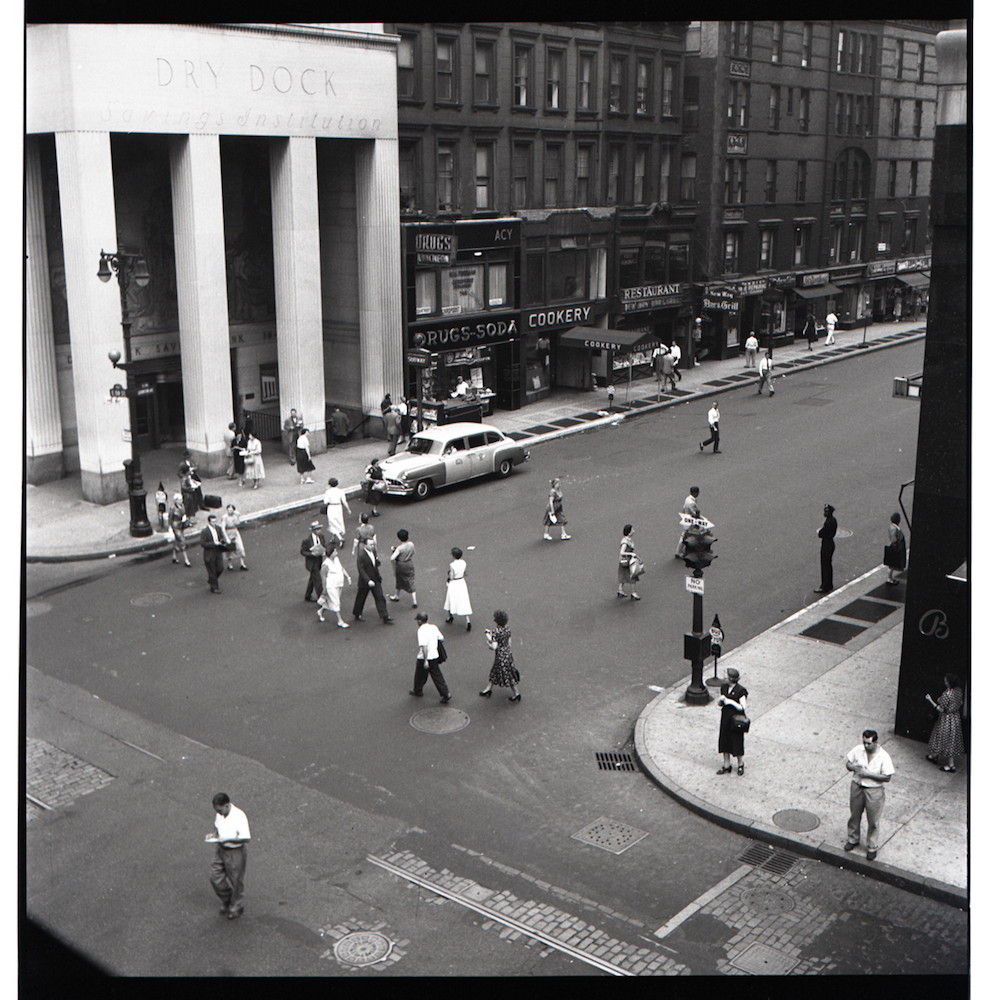

Image: 15 x 10 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

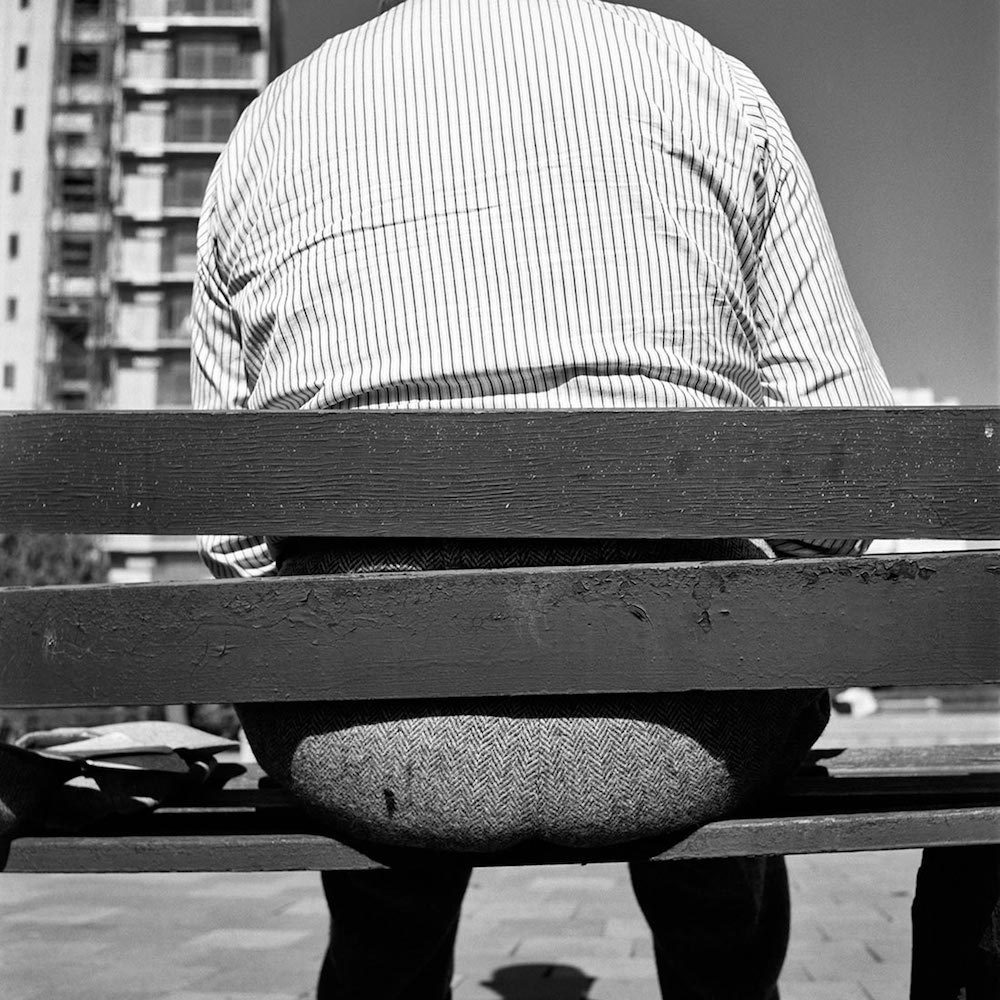

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

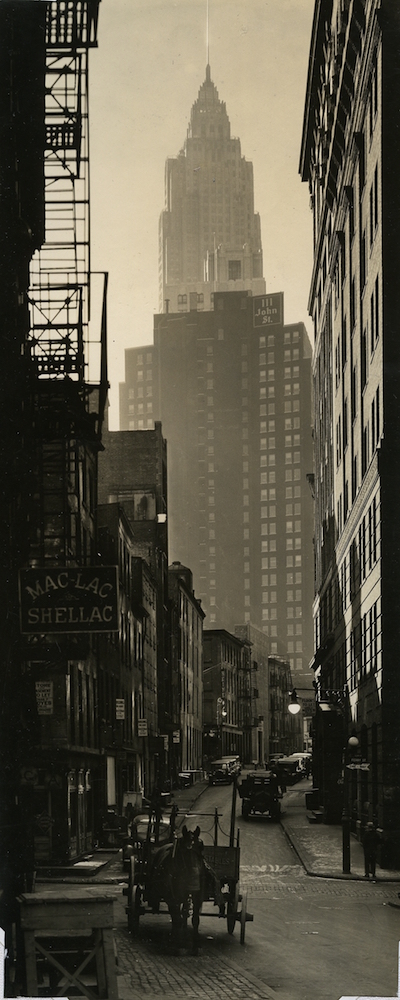

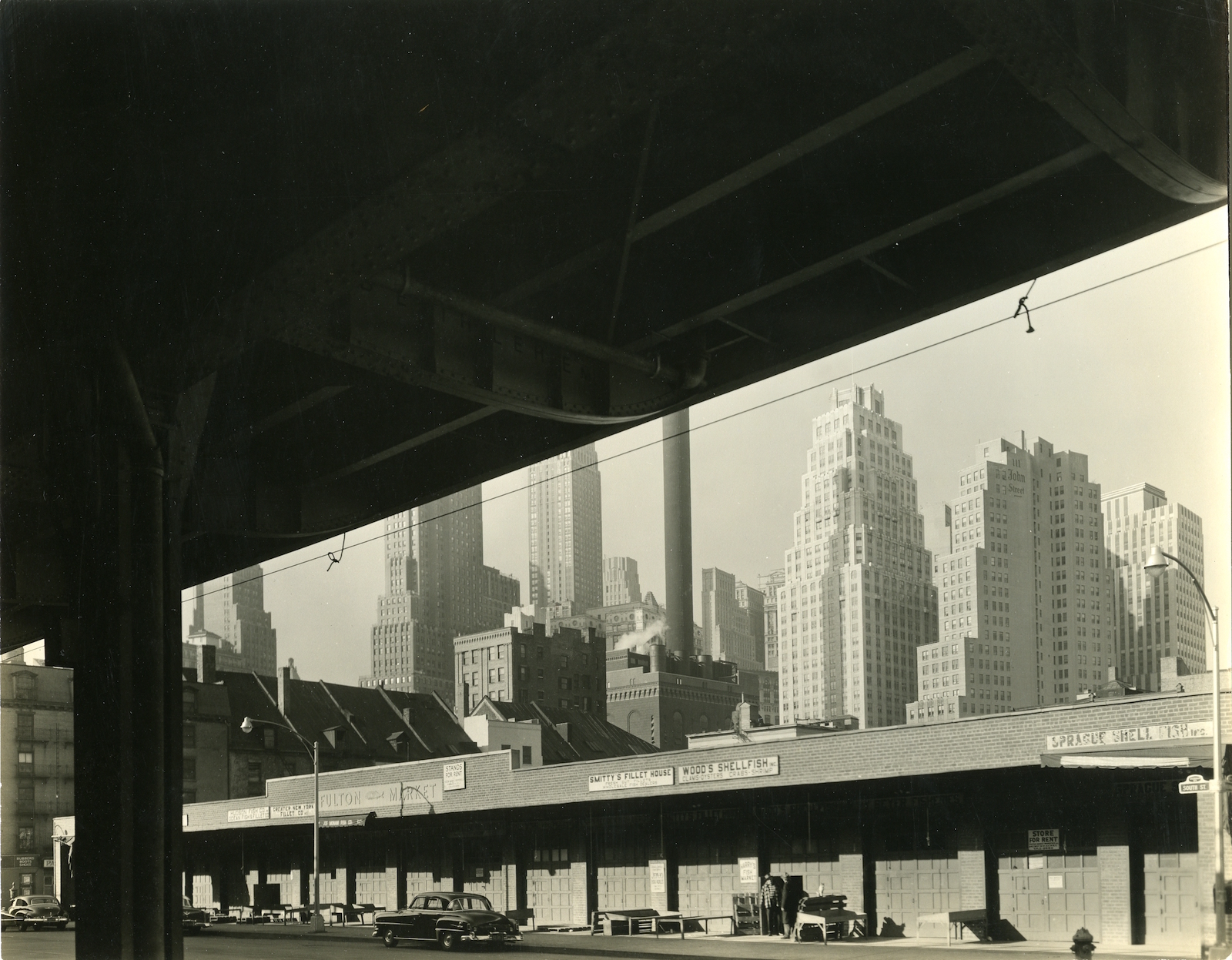

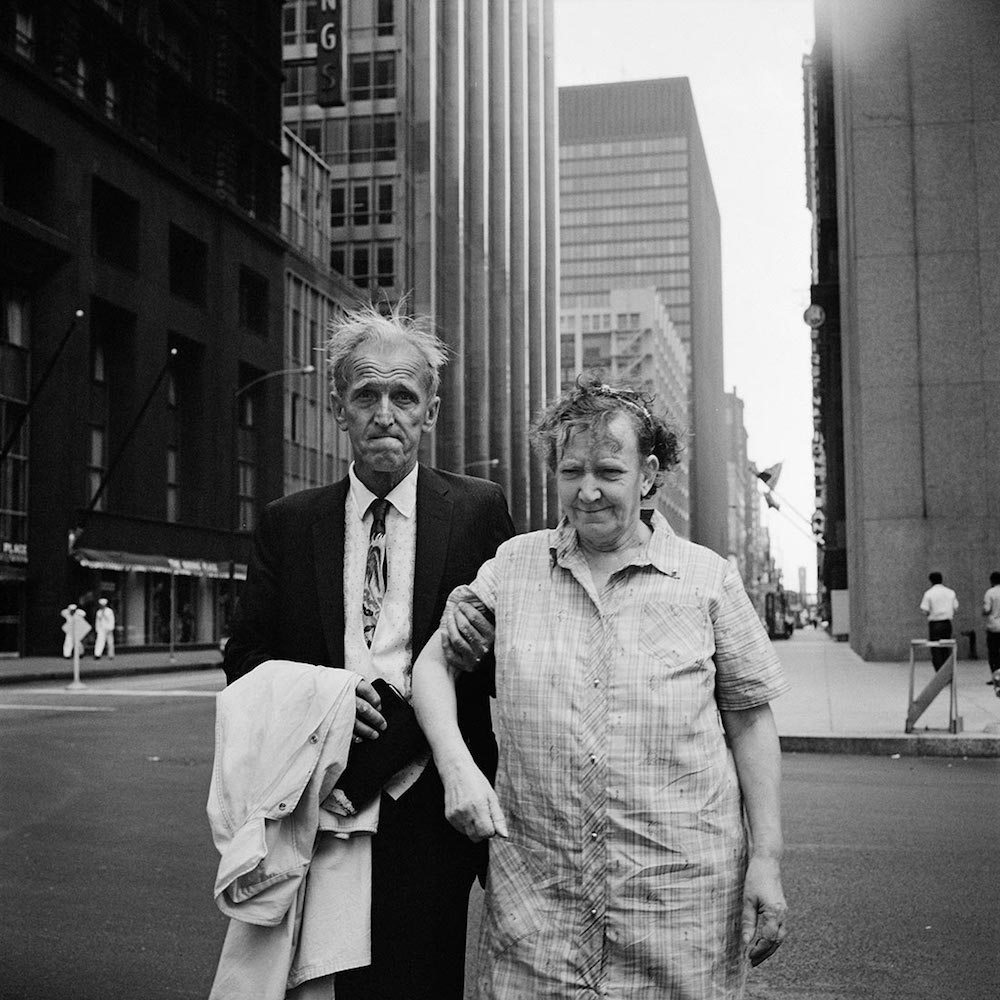

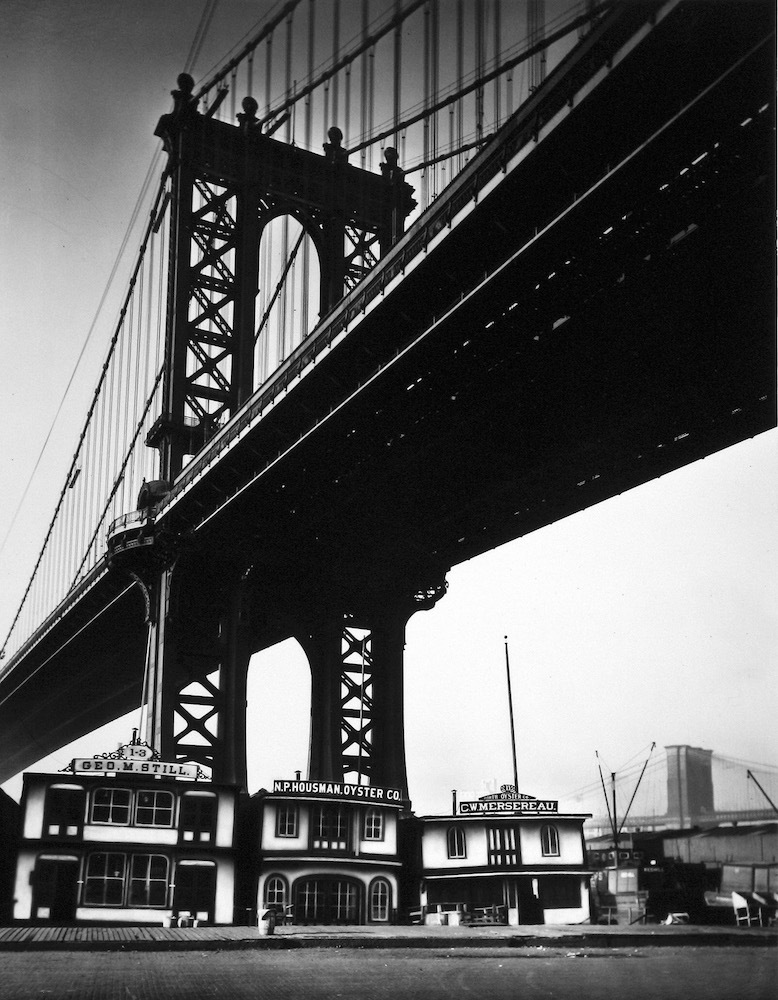

Image: 8 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches

Print: 8 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches

"Federal Art Project Changing New York" credit stamp with titled, date, location, and negative number in pencil on print verso

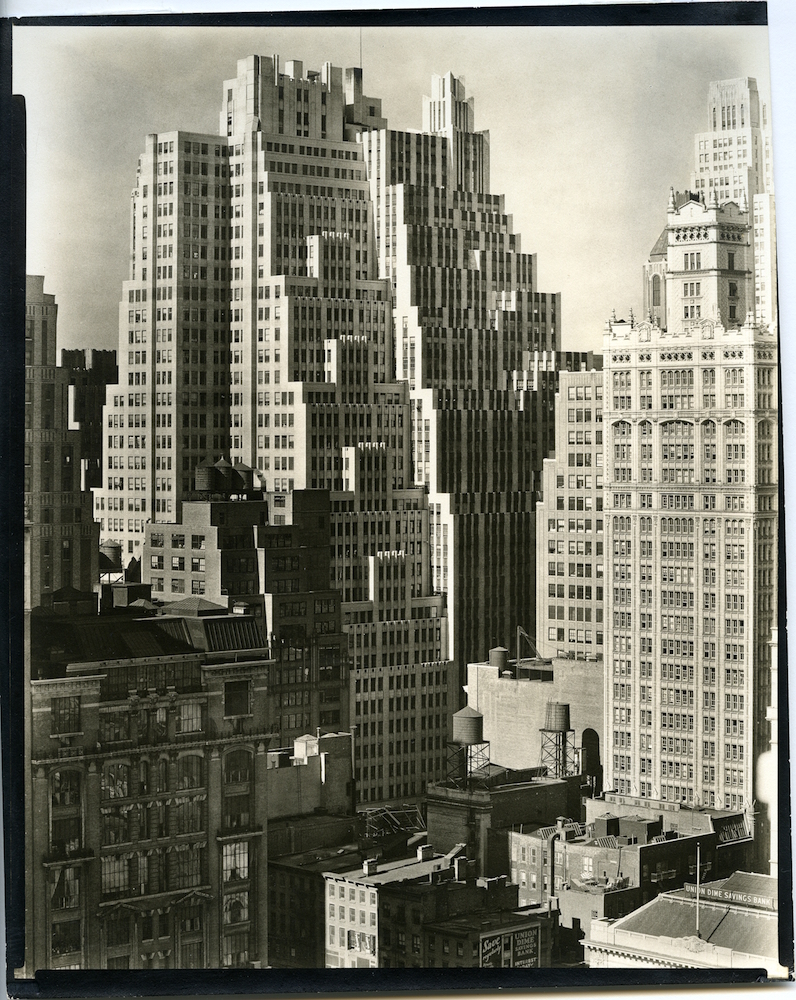

Image: 7,5 x 9,5 inches

Print: 7,5 x 9,5 inches

Signed, titled, dated, Neg. # 58-A and Code I.A.3 annotated in pencil, and "Berenice Abbott / Federal Art Project Changing New York" stamp on print verso

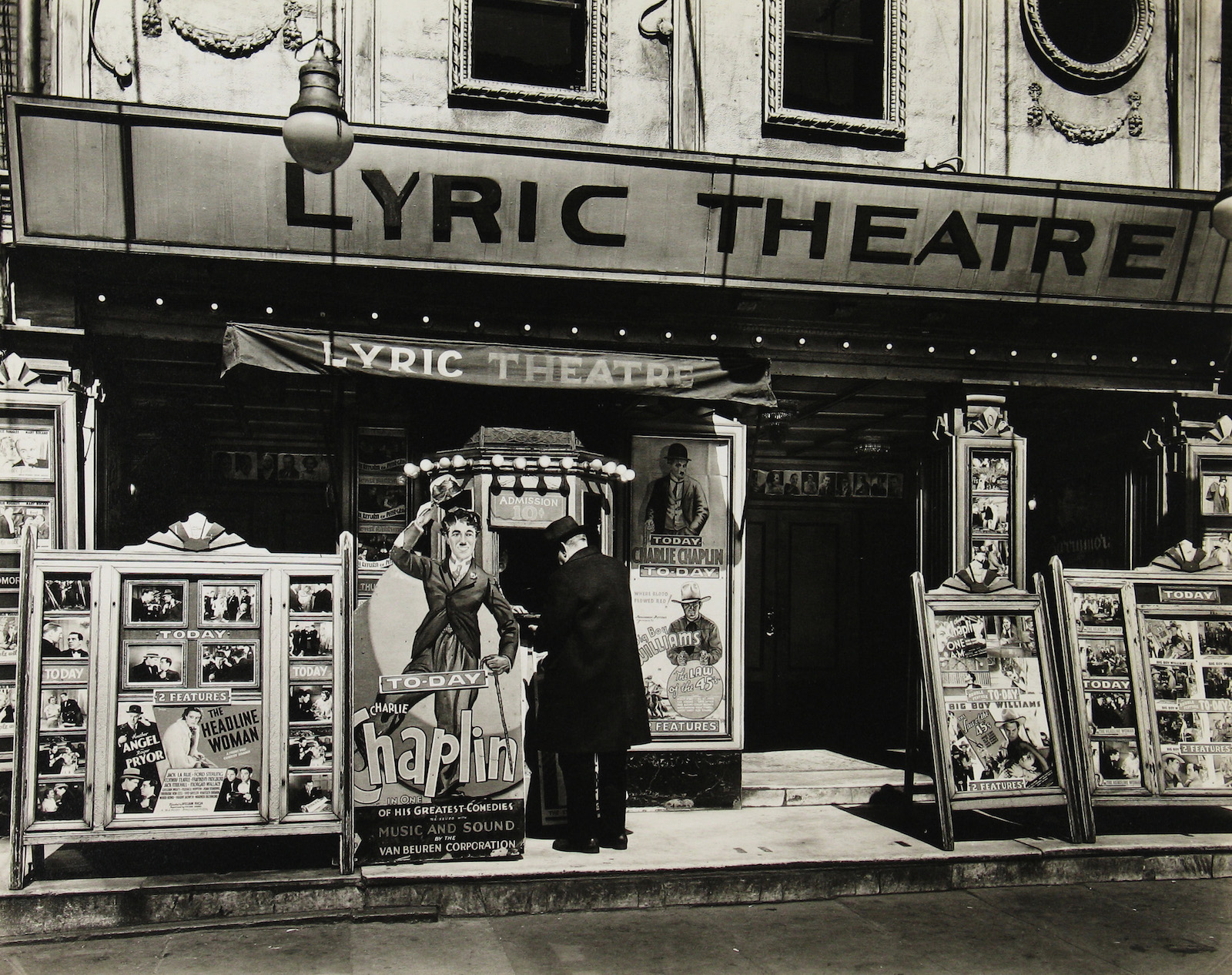

Image: 7 5/8 x 9 1/2 inches

Signed, titled, dated and annotated in pencil on print verso

Image: 6 5/8 x 5 3/8 inches

Photographer's credit stamp on print verso

Image: 8 x 12 inches

Signed in pencil, and photographer's 50 Commerce Street address stamp on print verso

Image: 10 1/2 x 11 inches

Print: 24 x 30 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount vero

Image: 11 1/2 x 10 3/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount vero

Image: 12 x 10 1/4 inches

Print: 18 3/4 x 16 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount vero

Image: 16 x 15 1/4 inches

Print: 24 x 30 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount vero

Image: 19 1/2 x 15 1/2 inches

Print: 24 x 30 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount vero

Image: 10 1/4 x 13 1/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 7/8 x 10 5/8 inches

Print: 20 x 16 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 10 x 15 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 10 5/8 x 10 1/2 inches

Print: 17 1/2 x 16 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 9 1/2 x 7 1/2 inches

Print: 17 x 14 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped "Abbot, Maine" on mount verso

Image: 12 1/2 x 10 1/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

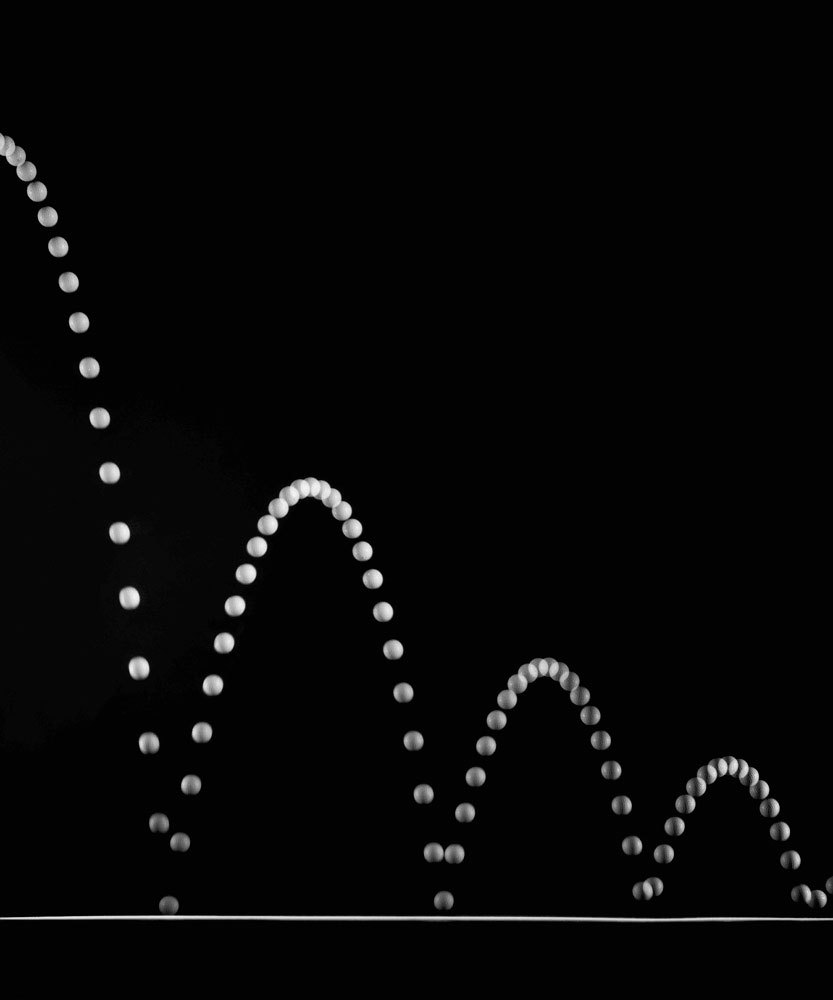

Image: 13 x 9 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

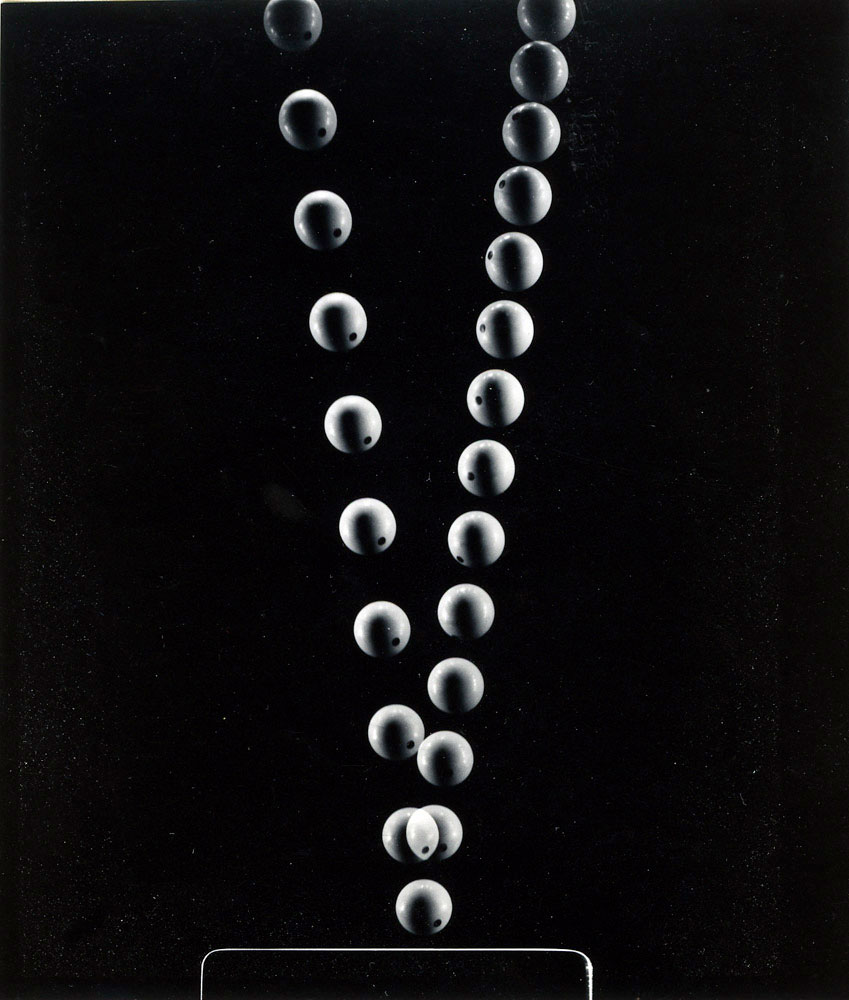

Image: 13 1/4 x 9 1/2 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

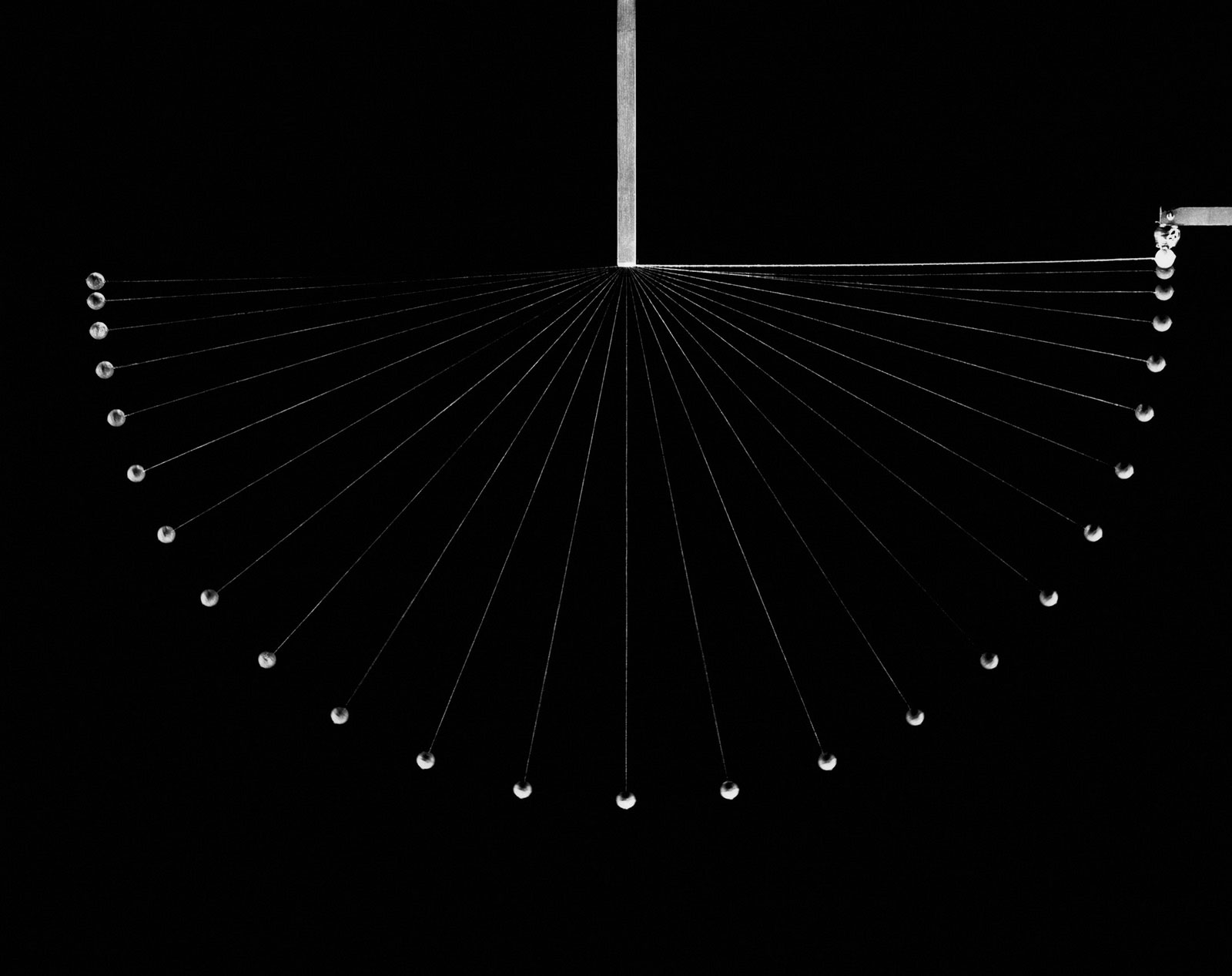

Image: 10 3/8 x 13 3/8 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

Image: 19 3/8 x 15 3/8 inches

Print: 24 x 30 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, Commerce Graphics stamp on mount verso

Image: 10 1/2 x 13 3/8 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 1/2 x 9 3/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 10 5/8 x 13 1/2 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 9 1/4 x 7 1/2 inches

Print: 17 x 14 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 x 10 1/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped "Abbot, Maine" on mount verso

Image: 13 3/8 x 10 3/8 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 1/2 x 10 1/8 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 5/8 x 10 5/8 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped "Abbot, Maine" on mount verso

Image: 10 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 9 1/8 x 13 5/8 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

Image: 15 3/8 x 19 1/2 inches

Print: 24 x 30 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

Image: 19 1/4 x 4 3/8 inches

Print: 20 1/8 x 8 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 23 x 8 7/8 inches

Print: 35 7/8 x 20 1/8 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 19 1/2 x 15 1/8 inches

Print: 30 x 24 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 1/4 x 9 3/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 12 7/8 x 19 1/4 inches

Print: 24 x 30 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 1/4 x 10 1/4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 15 1/2 x 19 1/2 inches

Print: 30 x 24 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, Commerce Graphics stamp on mount verso

Image: 15 1/2 x 19 1/2 inches

Print: 30 x 24 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped "Abbot, Maine" on mount verso

Image: 19 x 14,7 inches

Print: 30 x 24 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 19 1/8 x 15 inches

Print: 30 x 24 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Image: 13 x 10 1/2 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, maine on verso

Image: 4 7/8 x 19 3/8 inches

Print: 30 x 13 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

Image: 13 3/8 x 10 3/8

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

Image : 13.39 x 10.24 in ( 34,4 x 26,7 cm )

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

Image: 10 1/2 x 13 1/2 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed in pencil on mount recto, stamped Abbot, Maine on mount verso

Presentation

What is the connection between these two utterly different women? Berenice Abbott sought out the light, while Vivian Maier hid amongst the shadows. One indefatigably knocked on every door in order to get her projects off the ground; the other criss-crossed the globe on her own. Beyond their particular predilections, however, they were united by the same passion to document the real. They both lived without compromises; nothing and no one could get in the way of their vision. What they have left us are two singular bodies of work that are imbued with a spirit of freedom.

Press

PRESS RELEASE

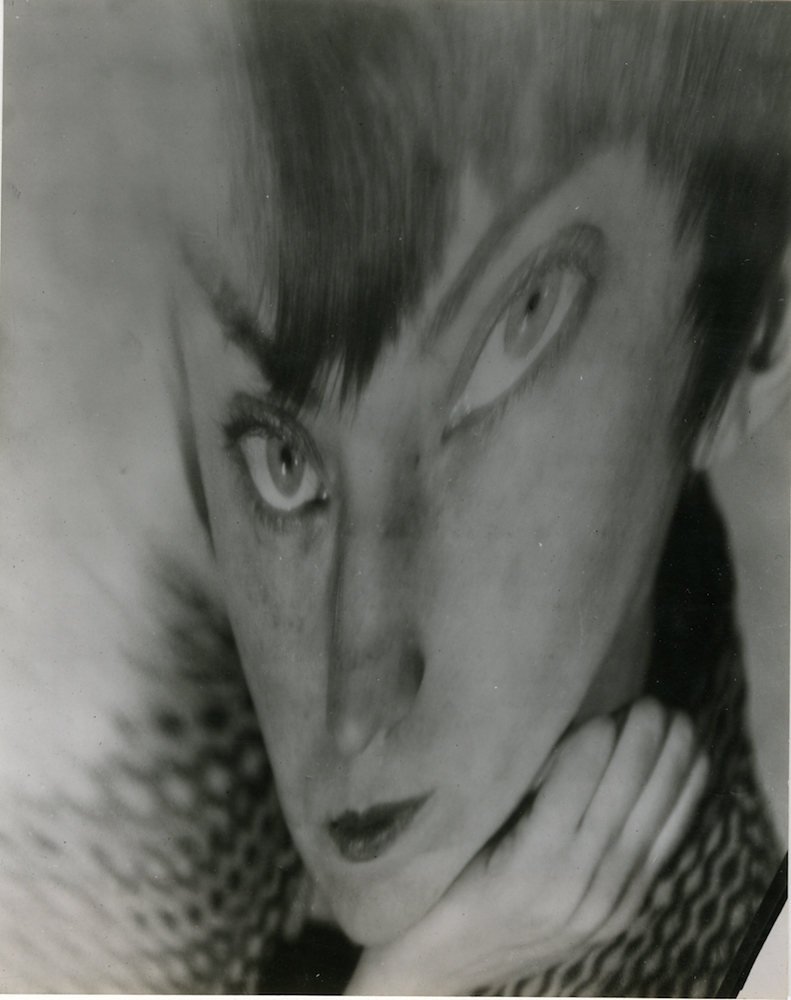

Berenice Abbott: No Frills

Born in 1898 in Springfield Ohio, Berenice Abbott posed nude for her compatriot Man Ray when she was johjhis assistant in Paris. It was Man Ray who taught her the arts of portraiture and of the dark room, and through him she met Eugène Atget, one of her neighbours on the rue Campagne-Première in the 14th arrondissement. “The shock of realism unadorned” she would later say of his prints. At his death, she purchased a number of his works, later selling them to the MoMA in New York in 1968 after having paid homage to them throughout her life, a life that ended in 1991 in Monson, Maine at the age of ninety-three.

If it is impossible to talk about Abbott without mentioning Atget it is because the young American had a particular attachment to the elder Frenchman, a genuine investment. It was as if Atget, who she said was able to see “the real world with wonderment and surprise”, had opened her eyes. Honoring his memory also meant choosing one aesthetic – documentary photography – rather than the pictorialism in fashion, which she found stunted, limited.

Her style was already effective from the very first portraits she made of the American exiles and the bohemians of the Left Bank. The models are seated, gesturing vividly, with striking profiles. There are no starchy effects, no flights of fantasy, only seriousness. She captures more than the whole of her subjects, she captures their super-ego. That fullness lies at the heart of Changing New York, a vast project that she undertook from 1935 to 1939, when she had left France to return to the United States. It was a difficult return after the crash of 1929, but New York was in full vertical swing, bursting with enthusiasm. Skyscrapers, bridges, shop fronts, this “fantastic” city fit with her human scale. Her representation of New York is free of nostalgia; for her it was about showing “the past bumping into the present”. Her photographs are surprising, sometimes invented, like the great hall of Pennsylvania Station whose utter solemnity she manages to evoke, as if the station were a film set waiting for movie stars rather than ordinary passengers. She found success with Changing New York.

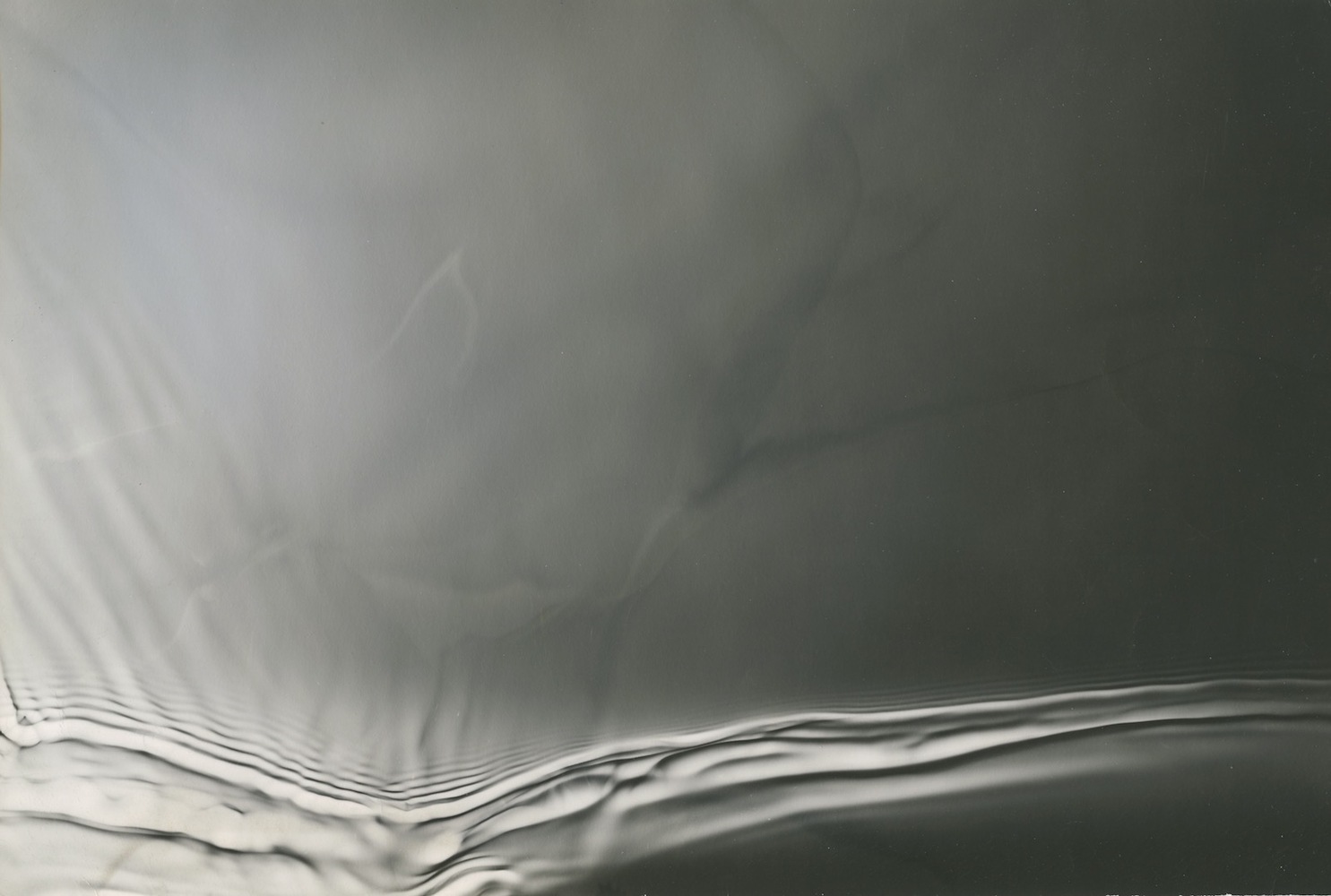

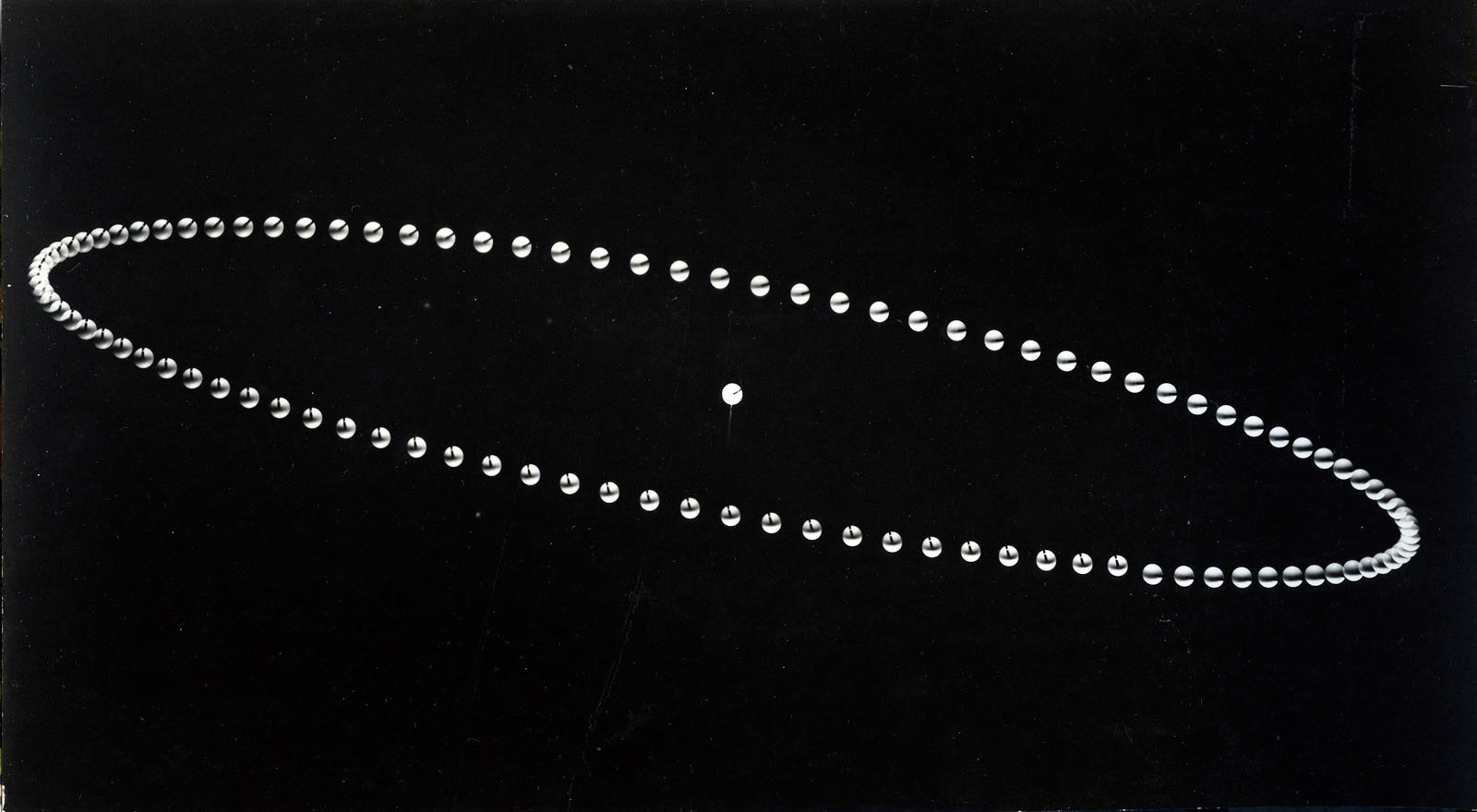

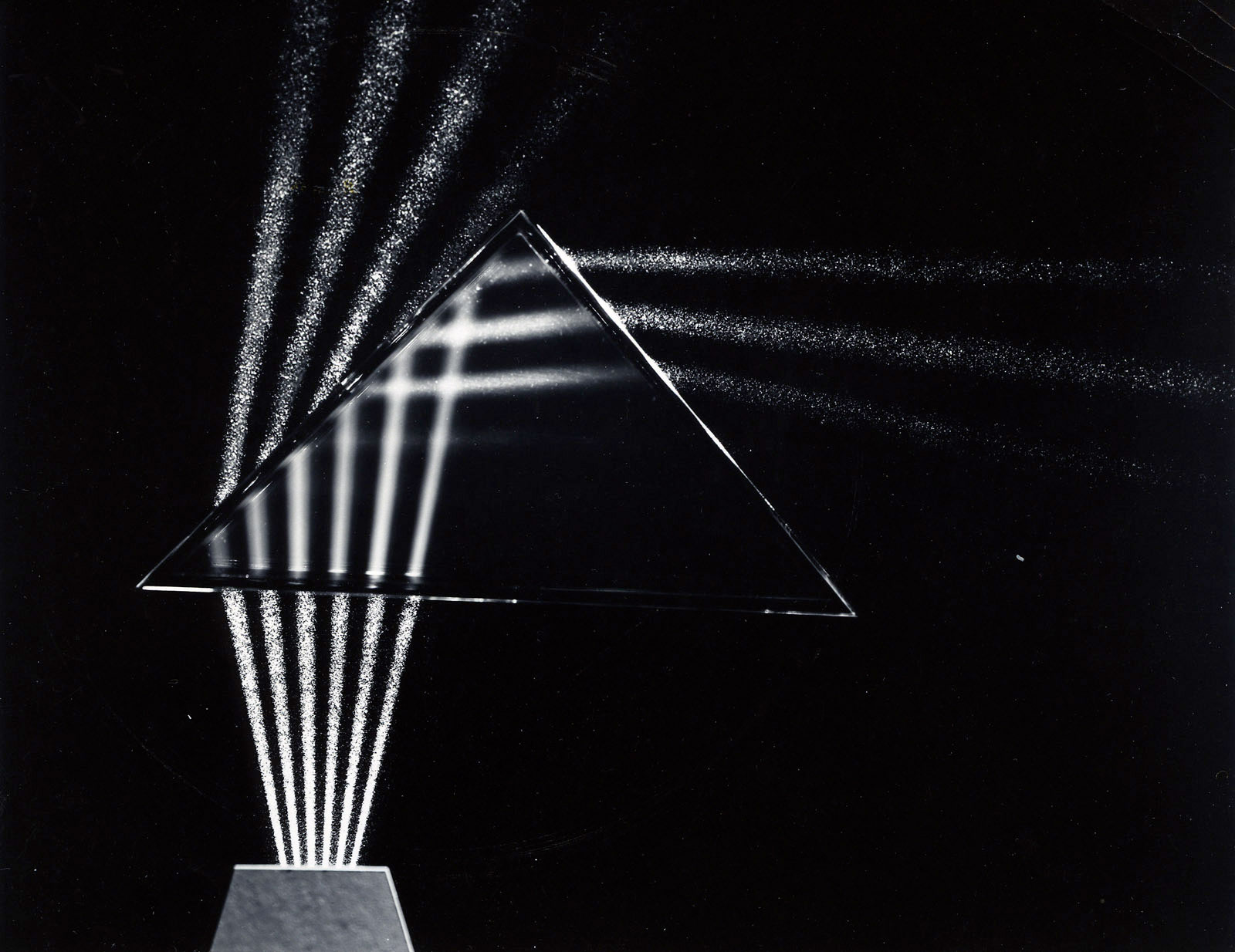

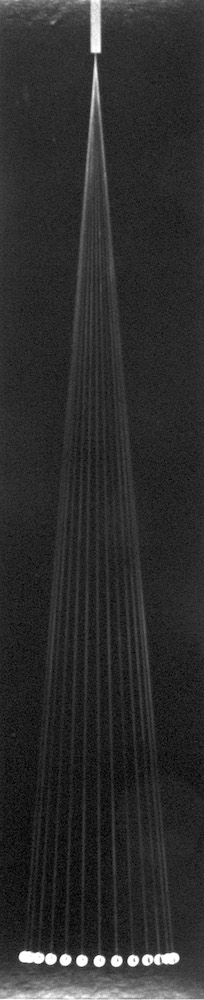

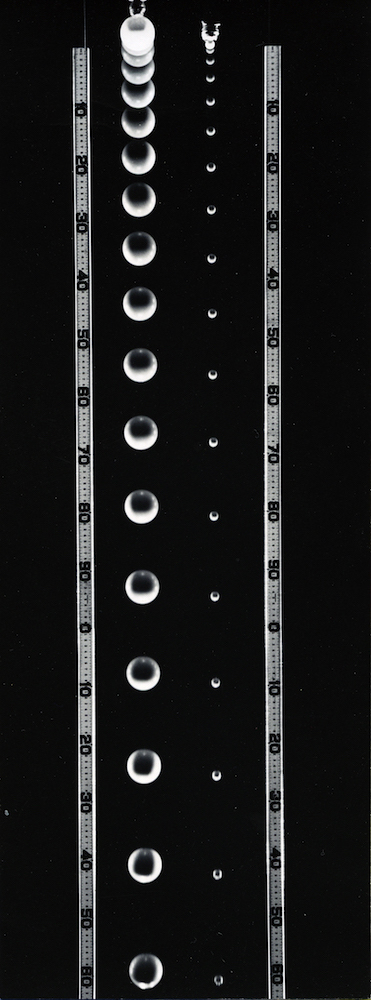

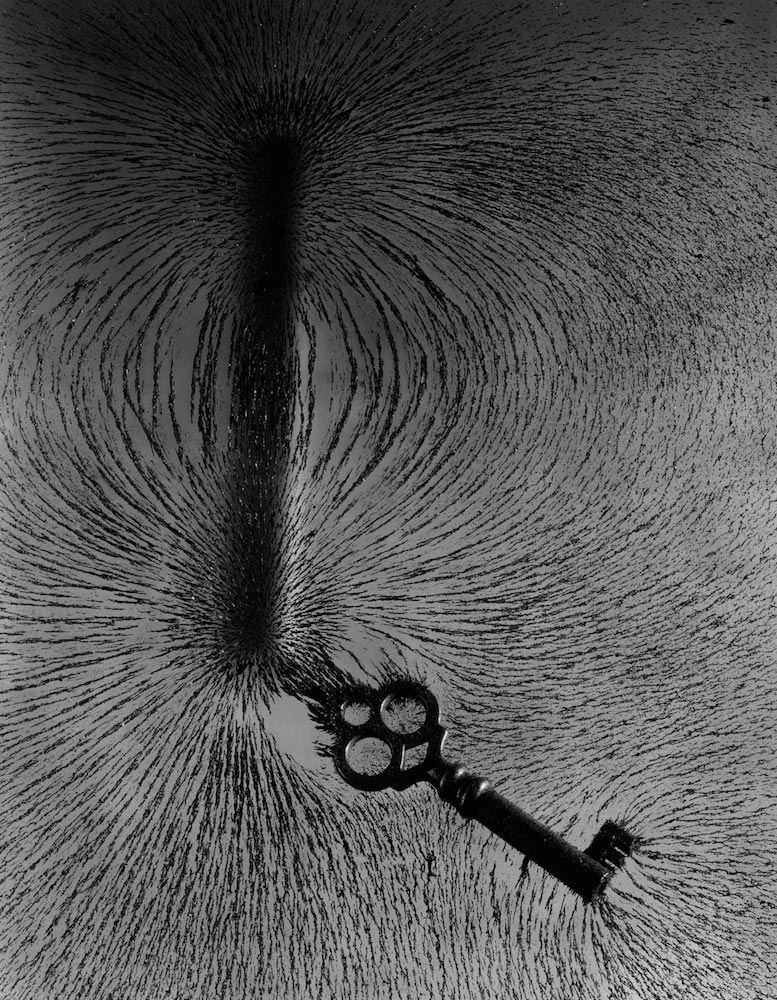

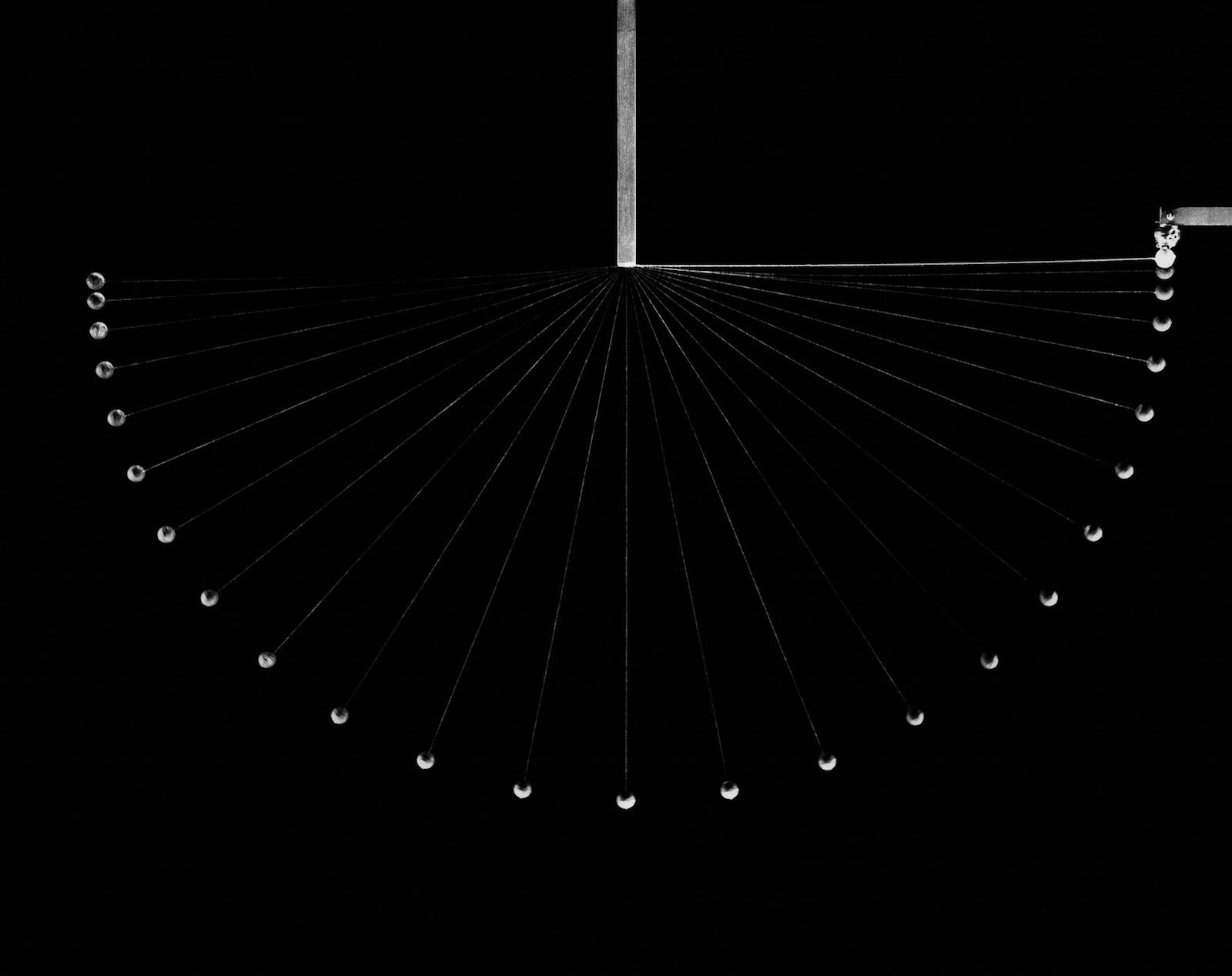

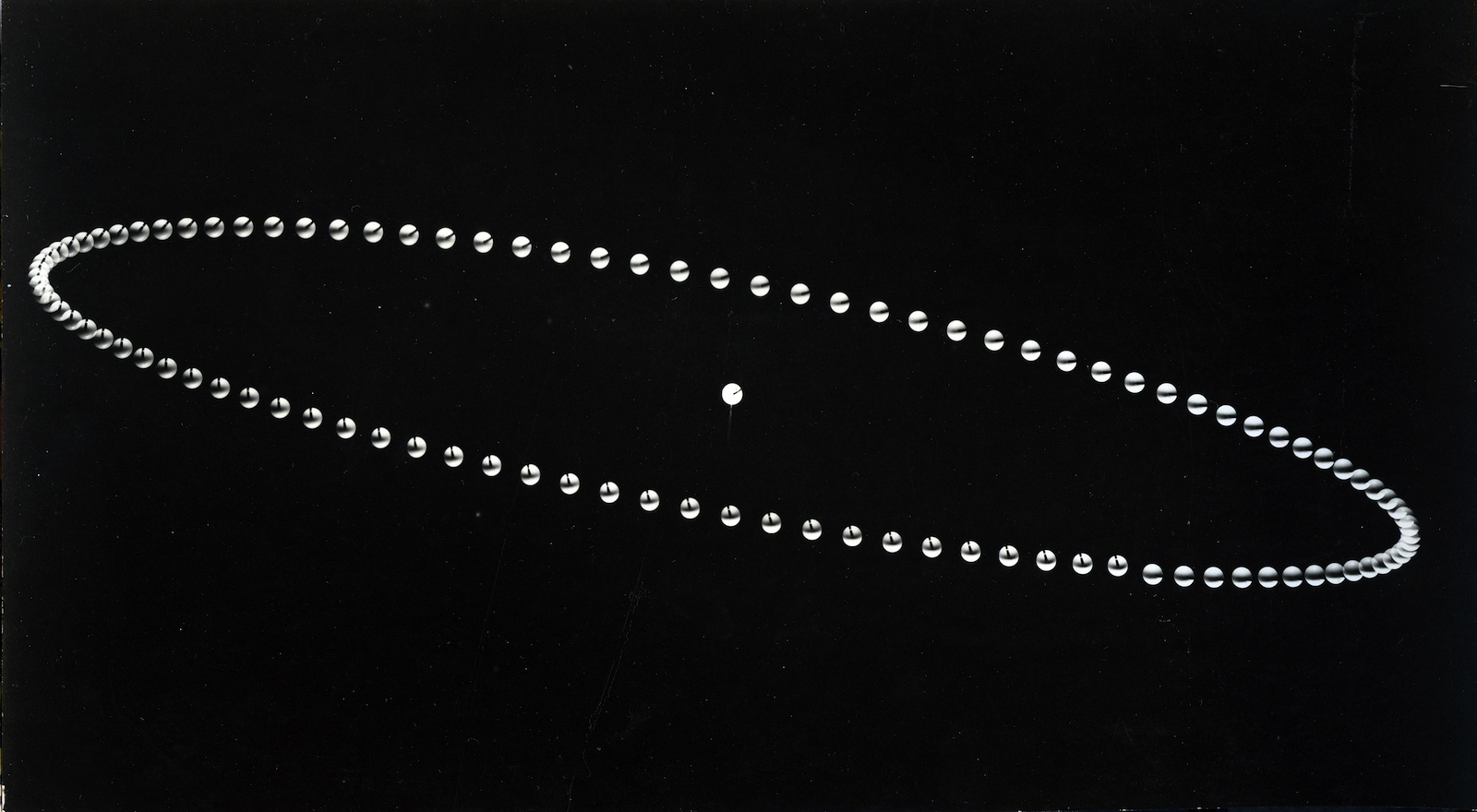

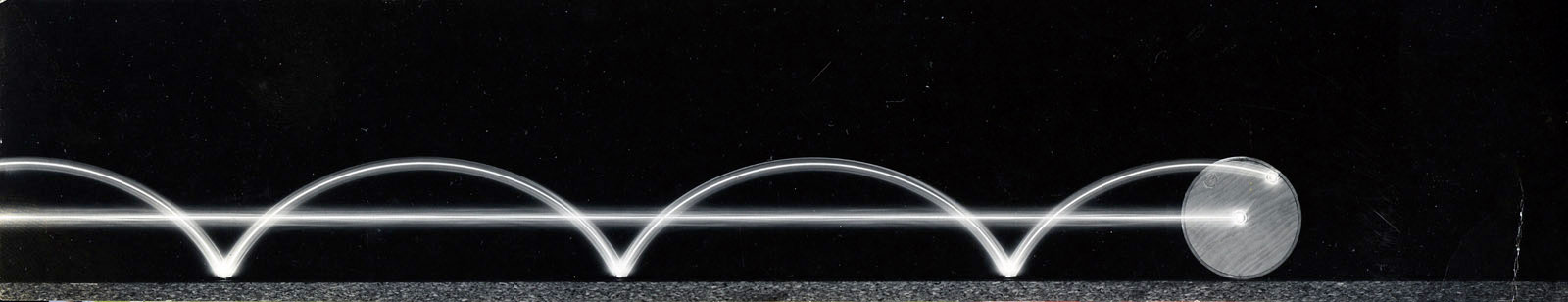

Later on, she travelled up and down the East Coast from Maine to Florida on Route 1, and from 1958 to 1961 she worked for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, indulging in the scientific passion she had discovered in 1939. Out of context, her hypnotic views reveal invisible experiences, magnetic fields for example, and unknown planets being born, a bullet ricocheting. They form a dialogue between imperceptible matter and a technician enamored of physics.

“The truth is hard to find. It takes a lot of work”, Abbot, an avid ping-pong player, confided to the New York Times on February 17, 1983. She had once imagined herself becoming a journalist. Through photography, Berenice Abbott imposed her critical vision, paradoxically rich with a certain austerity. No, there are no frills. She goes toe to toe with reality, without losing her footing.

Brigitte Ollier

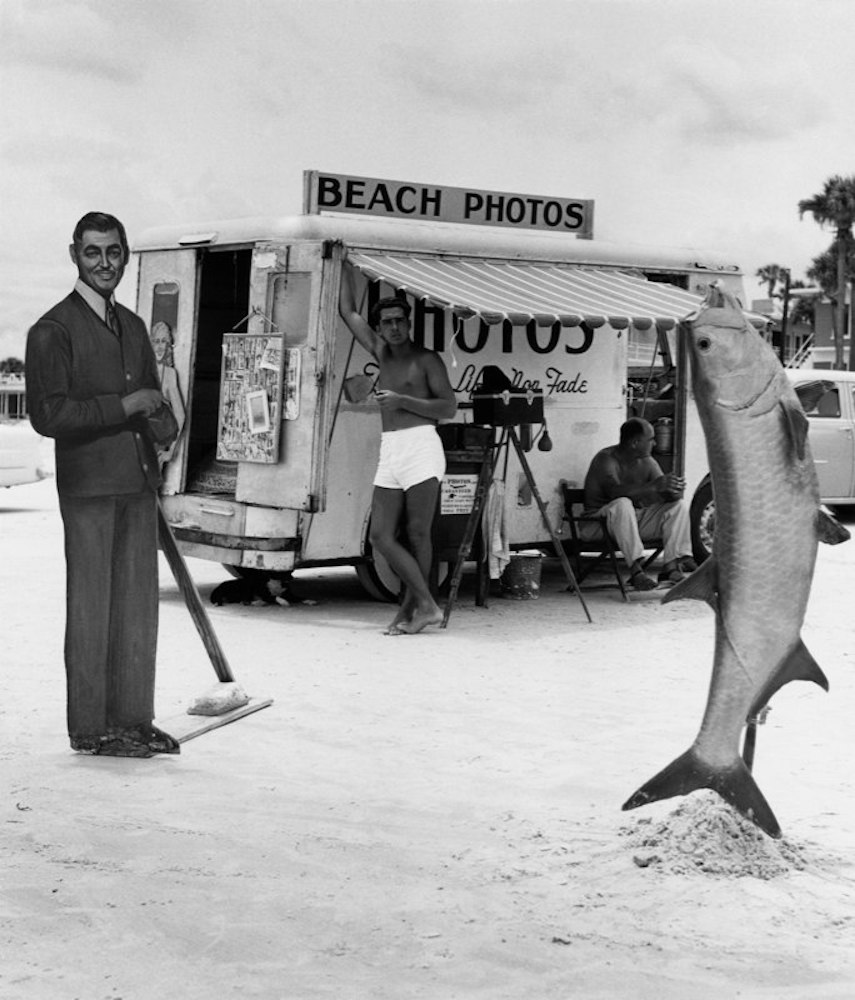

Vivian Maier: A Dreamed Life

When Vivian Maier came on the scene, she shattered the reigning dogmas of our gaze. It was if all of a sudden, Nadar, the French national treasure, had turned out to be a woman all along, making us rethink everything accordingly. It’s a bit of a stretch perhaps, but only just. At the outset, Maier did not actually have anything special to offer the history of photography, much less to be a part of it. And yet, in record time, this American woman became as famous as the Mona Lisa. She has received top billing for a long time and scores of specialists scour her past, hoping to finding something there to work with.

Maier was born on February 1, 1926 in New York and died on April 21, 2009 in Chicago. In between, she and her French mother visited the department of Hautes-Alpes, and in 1932 the valley of Champsaur. Her all-consuming passion was photography, which she engaged in with utmost discretion. Beginning with a Rolleiflex, and then a Leica, she set about photographing the streets of New York and Chicago, the passersby, the poor people on the sidewalks, dolls thrown in wastebins, bejewelled zealots, late-night Cinderellas... She also created a series of self-portraits that reveal her uncommon eye: she plays with reflections almost to the point of obsession, at times bordering on fear. When she used the inheritance her great-aunt had left her to travel the world, she continued to take photographs, but without showing what she had seen. And this is one of the mysteries of Vivian Maier, the self-taught photographer who earned her living as a governess: she refused to step out of the shadows. Complete anonymity. Was it a question of a lack of means, or of time, or of place? A wish to opt out of the world?

During an auction in Chicago in 2007, John Maloof, one of the main buyers, paid $400 for boxes and suitcases that had belonged to Miss Maier. They contained between 100,000 and 150,000 negatives, plus 3,000 prints and hundreds of undeveloped Ektachrome rolls. Quantity has never been a measure of talent, but what Maloof had in his hands, in conjunction with the material from Jeffrey Goldstein and Ron Slattery, was the stuff of dreams.

From 2007 to the present day, there has been a constant quest to discover the real Vivian Maier. Films, books, exhibits... the "Mary Poppins of film rolls" has been the subject of all manner of commentary (not all necessarily stupid; there is a plethora to choose from). One exhibit organised in France, by the Jeu de Paume in 2013, revealed that Maier, who loved the cinema, also made Super-8 films, and that she was a formidable interviewer. None of the haziness surrounding her is likely to dissipate anytime soon. But one thing is certain: anyone who bought her prints will not regret it, for though Maier's talent was understated, you cannot help but want to stand by her side. In her shadow, no less.

Brigitte Ollier