La ville miroir

Image: 10 x

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 15 x 19 inches

Print: 20 x 24 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 13 x 17 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 14 x 17 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 13 x 16 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 18 x 10 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Image: 18 x 12 inches

Print: 20 x 14 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Print: 18 x 10 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Image: 13 x 16 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 14 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 10 x 12 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 14,8 x 9,8 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 14 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 10 x 13,4 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 13 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 10,2 x 13,3 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 10 x 13 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 11 x 15 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 10 x 13 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed and dated by the artist

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9,8 x 13,5 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed and dated by the artist

Image: 9 x 13 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed and dated by the artist

Image: 11 x 15 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 20 x 24 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 18 x 12 inches

Print: 20 x 14 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Image: 18 x 12 inches

Print: 20 x 14 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Print: 18 x 10 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Image: 12 x 18 inches

Print: 14 x 20 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Image: 12 x 18 inches

Print: 14 x 20 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Image: 18 x 12 inches

Print: 20 x 14 inches

Signed, numbered and dated by the artist

Image: 9 x 12 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 11,8 x 8,3 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 10 x 11 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 14 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed and titled by the artist

Image: 9 x 14 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 14 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 11 x 15 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 14 x 16 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 14 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 10 x 12 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Presentation

Sabine Weiss and Fred Herzog never tire of patiently, carefully strolling through cities. For it is urban landscapes, which they help us to see and feel, that best reflect their world, their obsessions, their commitments.

Beginning this 20th June, the Centre Georges Pompidou will host an exhibit on Sabine Weiss, and to add our contribution, we've brought together her images and those of Fred Herzog, who chose colour as the best way to express his identity.

PRESS RELEASE

MIRROR CITY

Sabine Weiss and Fred Herzog? Why bring together these two photographers? They belong to the same generation that came to photography in an effort to return to the real and to the human after the experimentation of the 1920s and the horrors of World War Two, but that seems hardly enough of a justification. A much stronger connection is that they have both made the city the center of their works, which belong to two different traditions, one European, the other North-American. Mirror City puts them face to face, inviting a comparison of the reflections they offer of post-war urban reality.

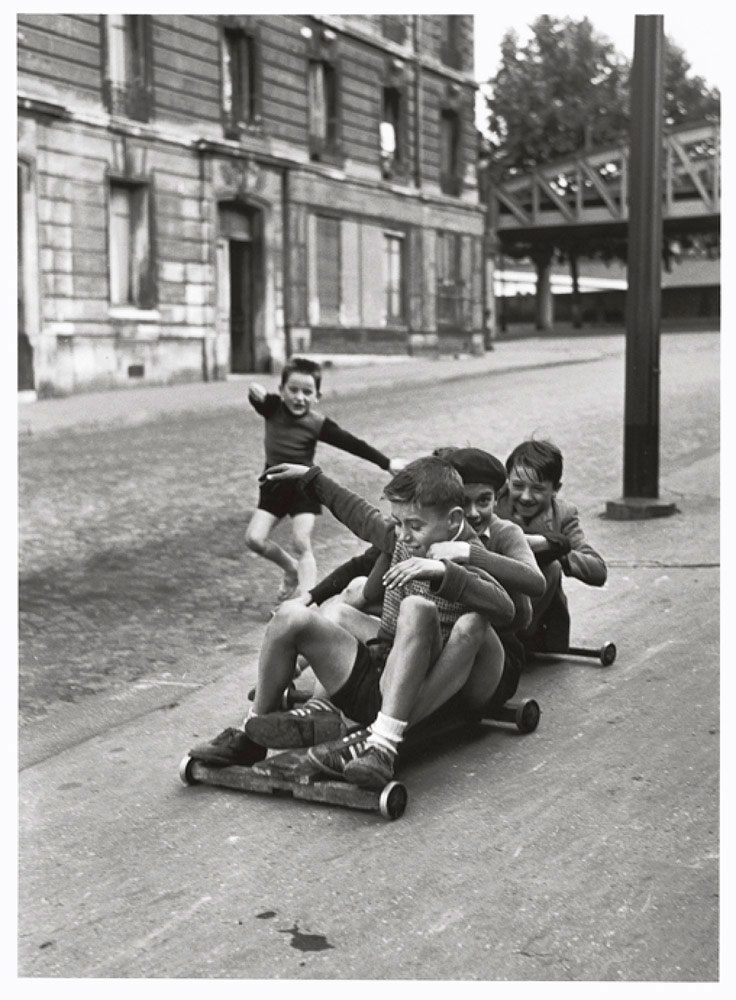

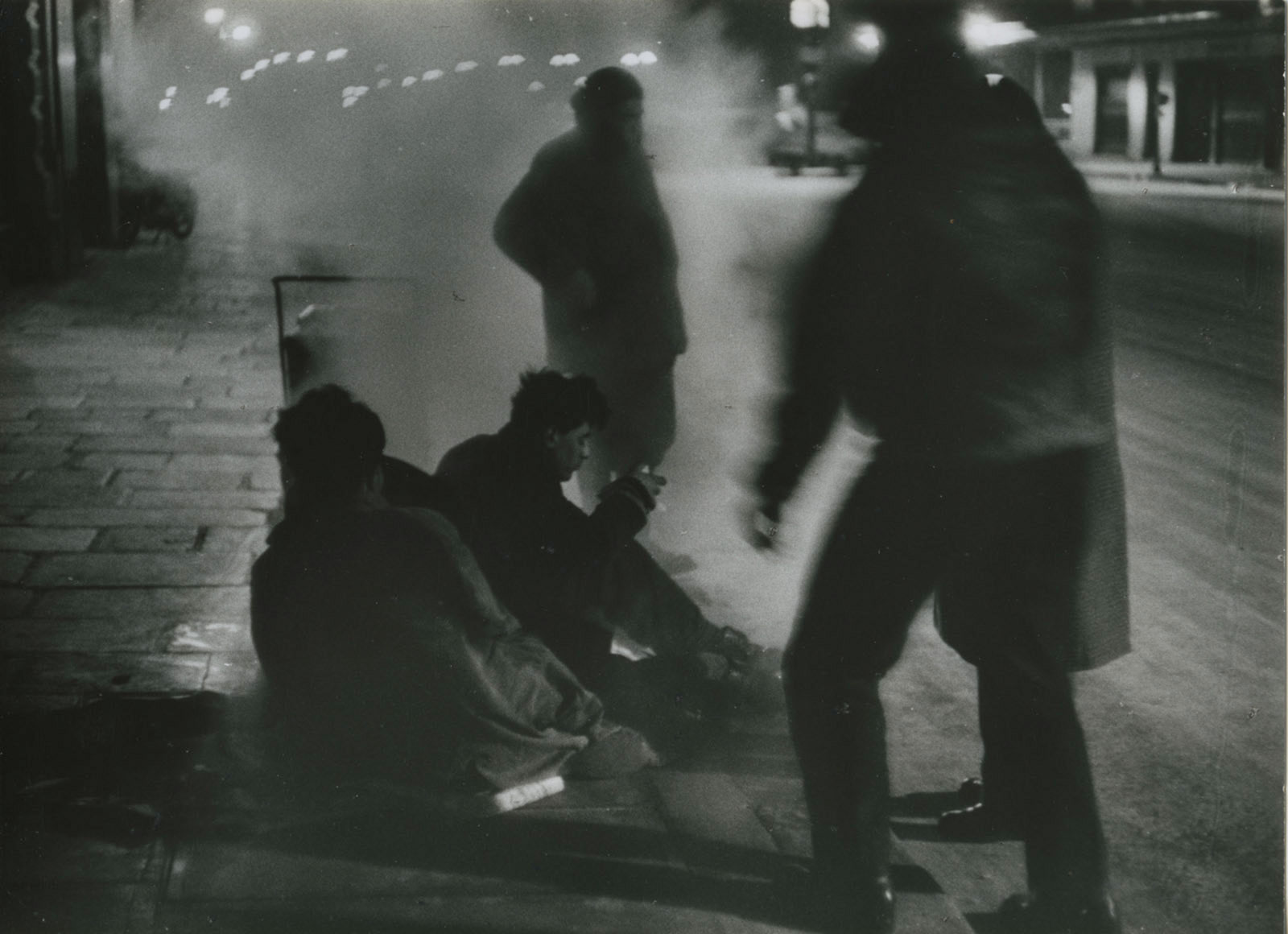

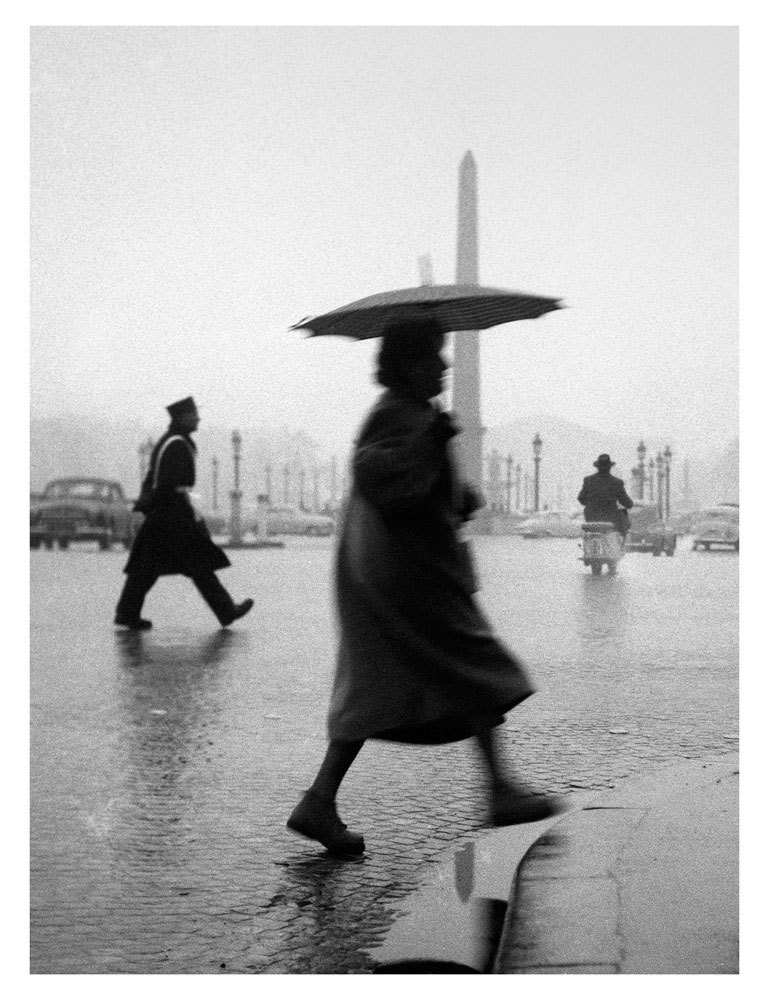

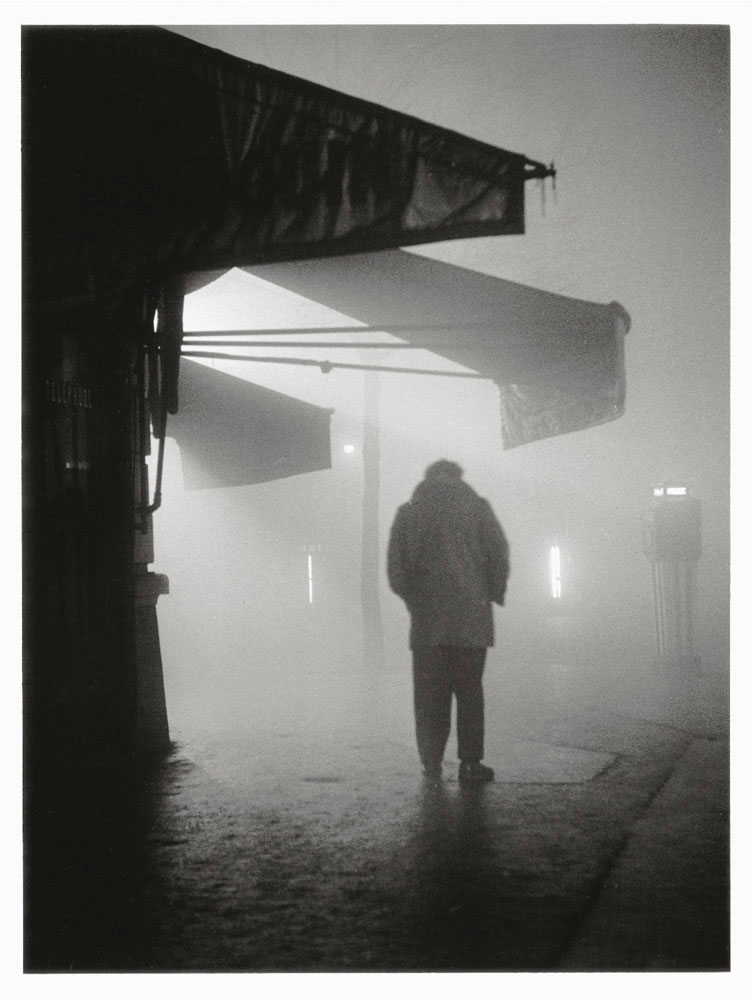

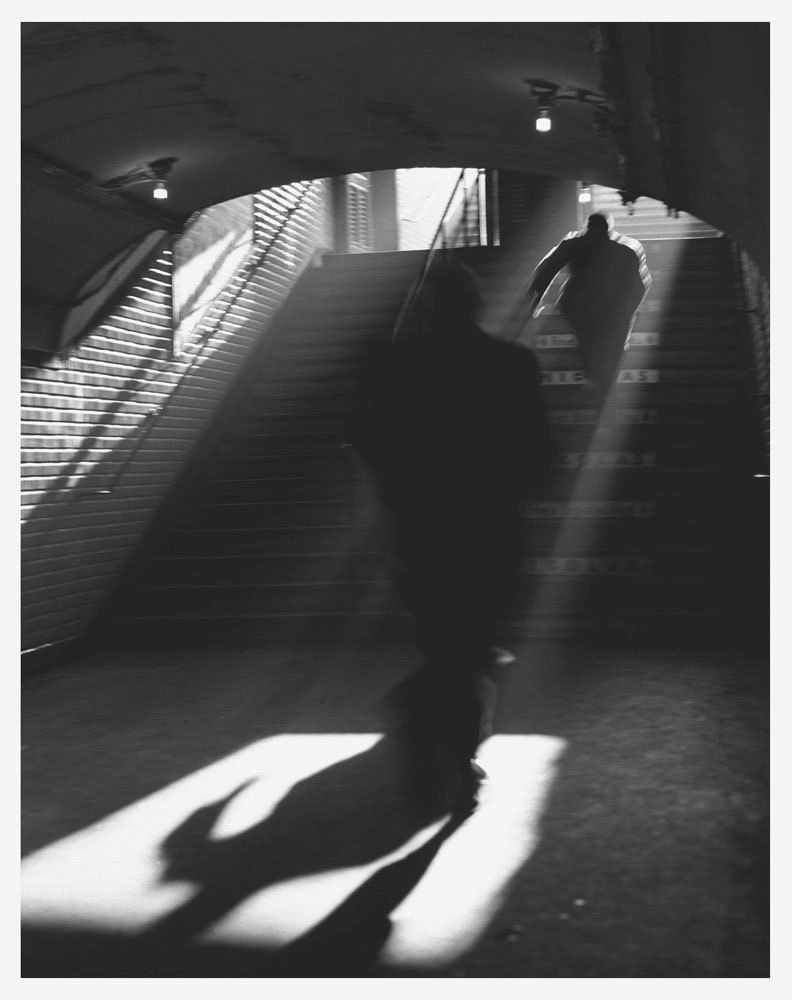

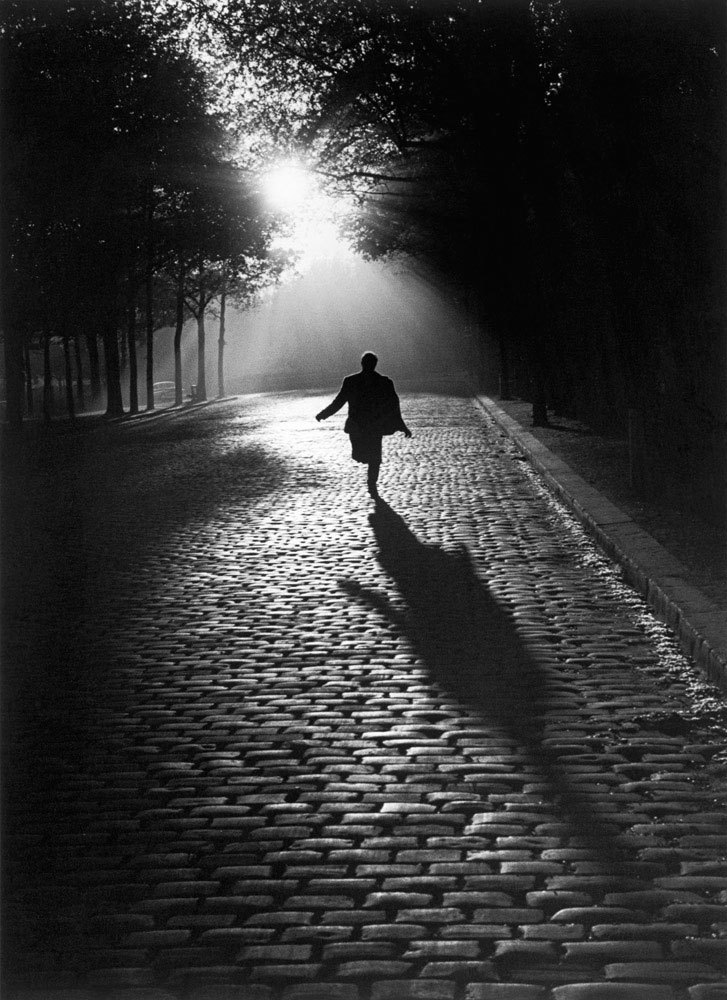

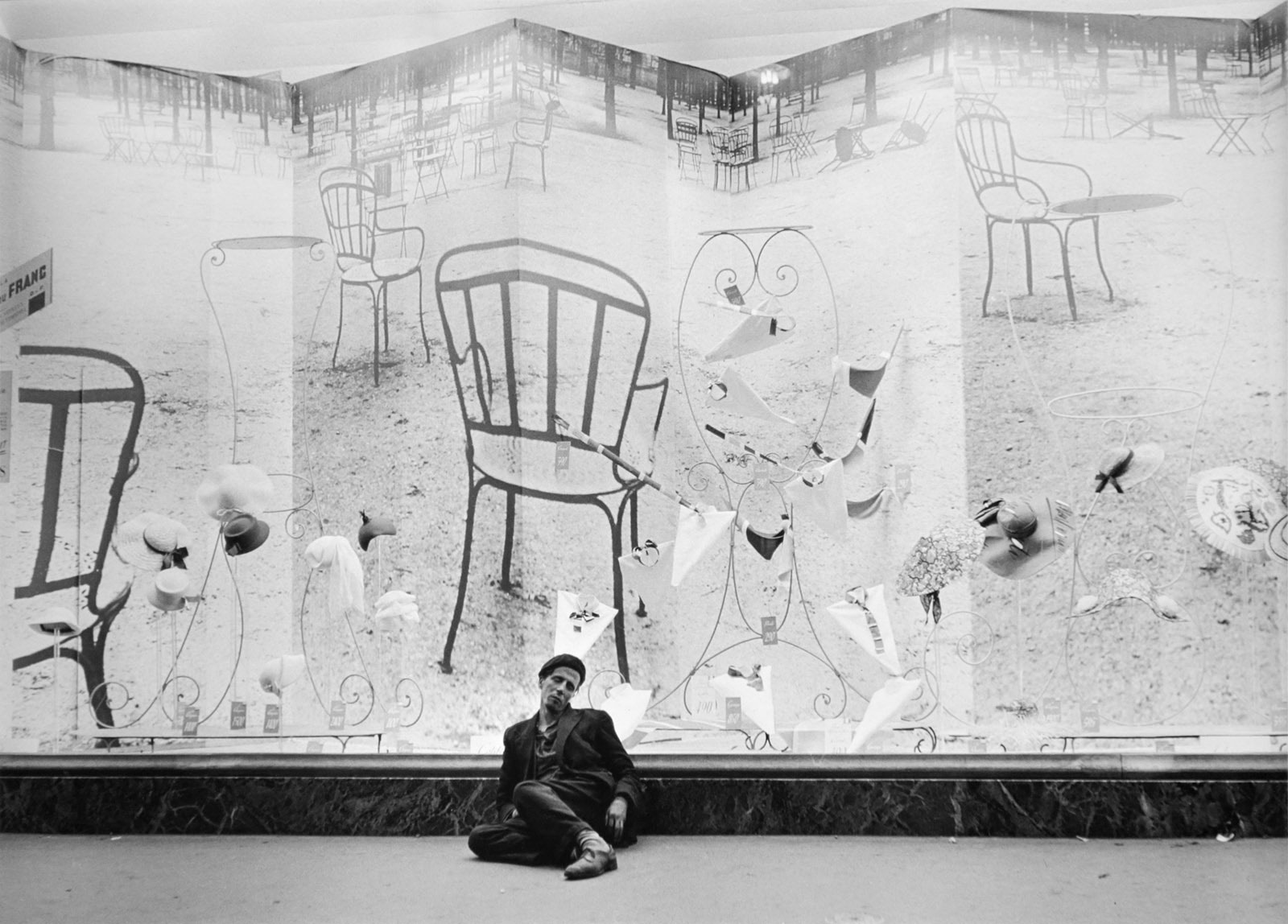

Born in Switzerland in 1924, Sabine Weiss settled in Paris in 1946, where she soon became one of the reporter-illustrators, or “dilettante photographers”, to use Willy Ronis’ term, who benefited from the rise of the press, engaging in reportage as well as fashion and advertising. During the 1950s – the period covered by this exhibit – Weiss engaged in personal projects, which she kept up through the middle of the following decade and eventually returned to. At the time, she looked closely at Paris, its streets, the vacant lots around the city, the men, women and children who filled it, or who tried to live there, those “lost souls” whom she liked to photograph, similarly to Robert Doisneau and Izis.

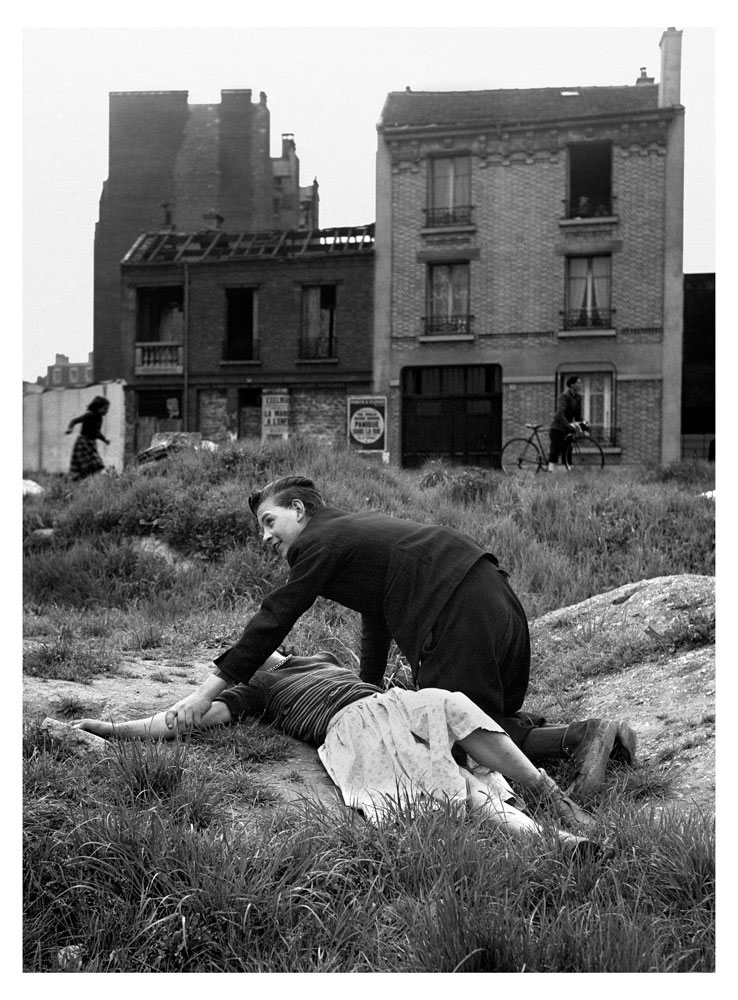

Her humanist photography privileged empathy over social critique, but still aimed to bear witness. Her images are simple and effective, their classical composition rebuffing avant-garde contributions such as close-ups and tilted or off-center points of view. They emphasize atmosphere, all while being carried, in Weiss' own words in Intimes convictions[1], by 'an intuition about what is the moment'. She goes further, when discussing L'Audace (1950), which shows an enterprising boy and a young girl pinned down on the grass, 'Even if we do not consciously register the little girl there running behind the lovers, we know that she is passing'.

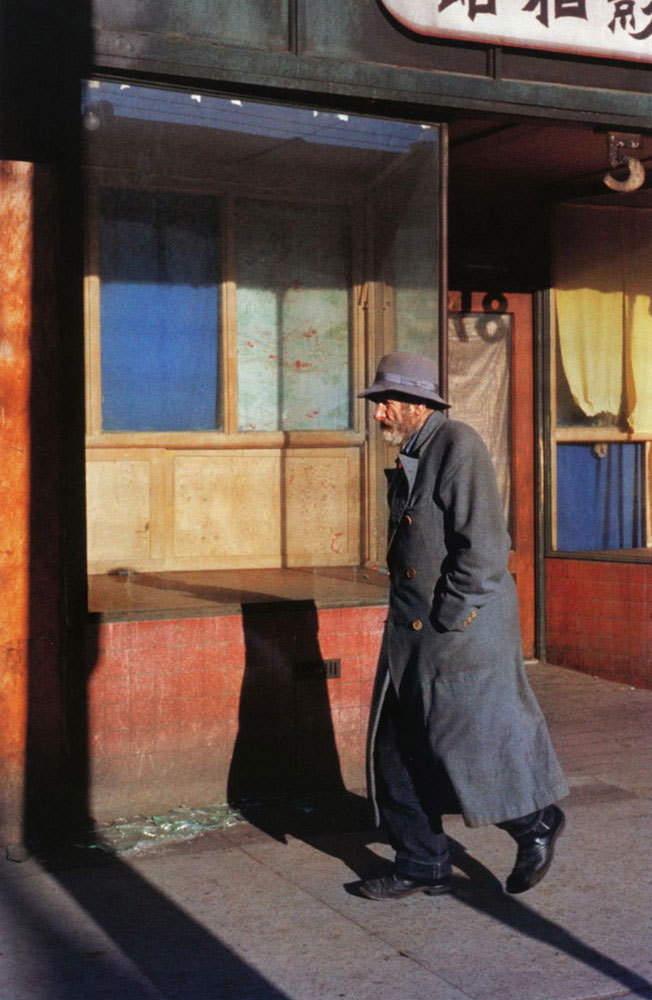

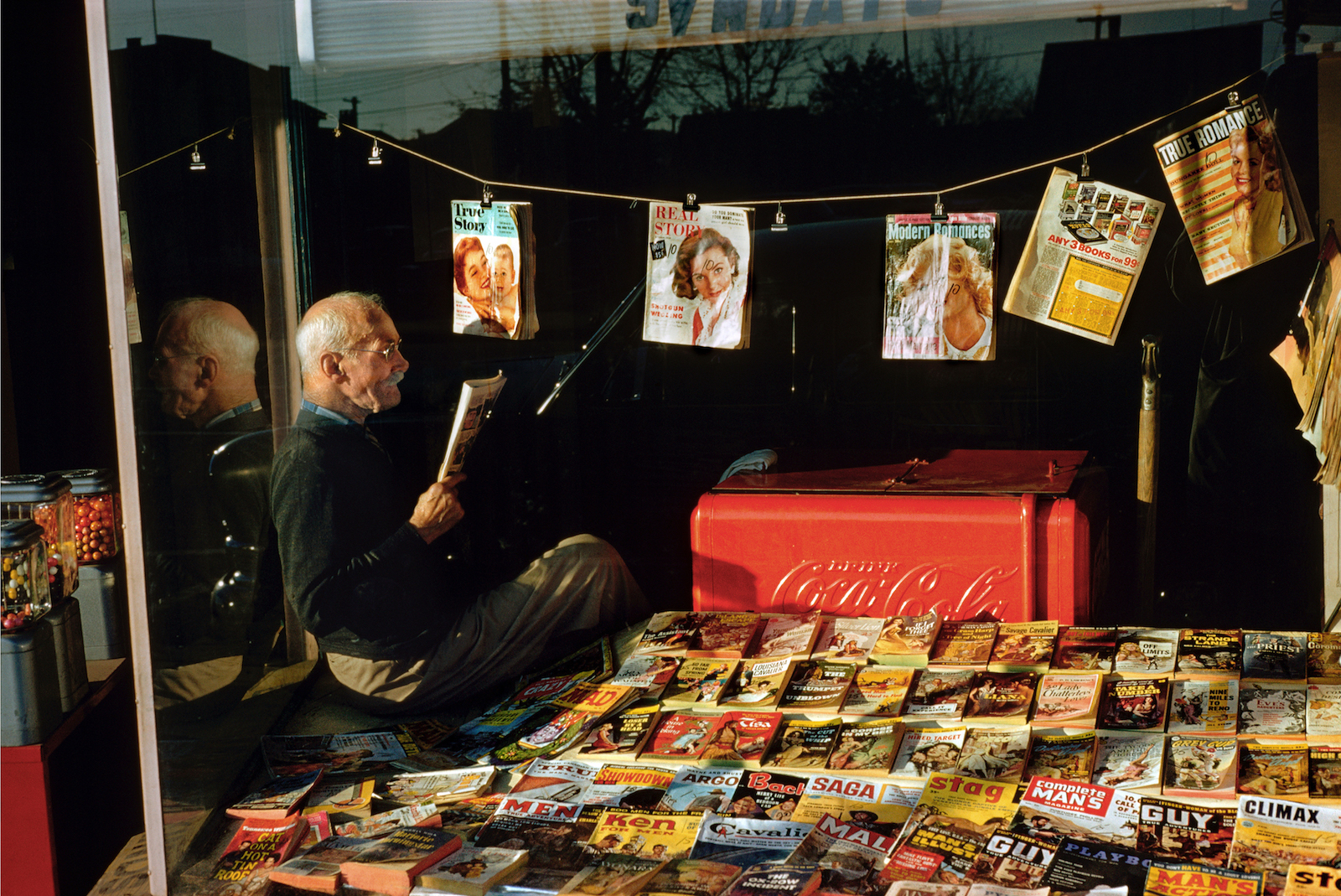

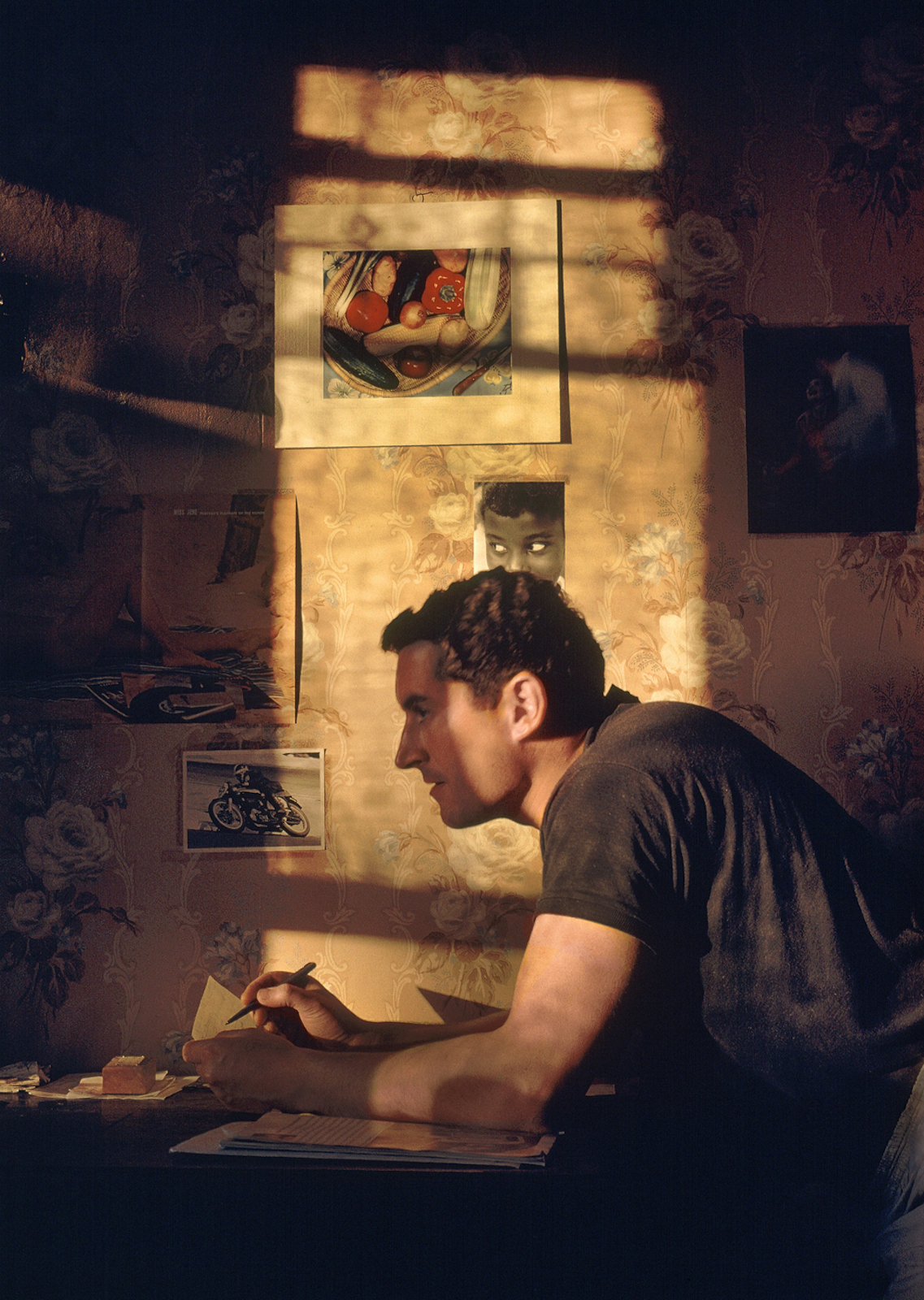

Fred Herzog's gaze turned more toward the United States than the Europe he came from. Born in Germany in 1930, he emigrated to Canada and settled in Vancouver in 1953. A medical photographer by profession, he dedicated a part of his free time to photographing his adopted hometown. His work is firmly in line with New York street photography, and the North American interest in vernacular or popular visual culture, as evidenced by the exhibit's neon signs, posters and comics. His approach is as realist as the books of Gustave Flaubert and John Dos Passos that inspired it, and his preferred tool to achieve this realism is colour.

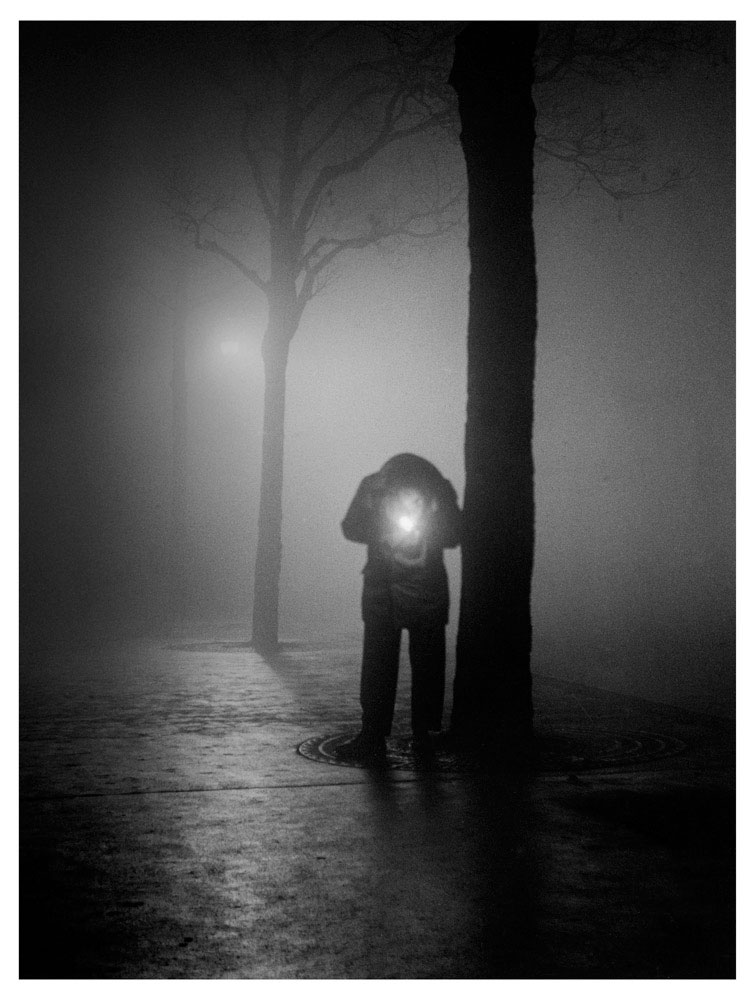

Herzog made his first colour photographs as early as 1953, before moving exclusively to colour four years later. At a time when the use of colour was the exclusive domain of amateur or commercial photographers, Herzog was one of the first – long before William Eggleston, Stephen Shore and others – to use it on the street for artistic reasons. Weiss also dabbled in colour, but only to satisfy certain commissions. For her personal work, she always chose black and white. In Intimes convictions, she explains that with black and white, 'one's mind is freer to dig deeper into the anecdotal, to go beyond it to reach a purer abstraction'.

In some sense, Herzog was trying to achieve the reverse effect by producing a detailed image that adheres to reality. He pragmatically adds that colour helps blend the figure into the background and makes it easier to read the image[2]. His balanced compositions confirm this priority of clarity and readability. Jeff Wall, another Vancouver artist, underscores Herzog's gentle affection[3]. In fact, Herzog's work contrasts sharply with the practice of his American contemporaries, such as Garry Winogrand, who reproduced jerky, brutal street scenes.

In contrast to his contemporaries' style of photography that makes everything striking, the subjects of Herzog's images sometimes seem miniscule, or even absent. For example, why in Hasting & Seymour (1959), does he photograph the woman and the little girl from the back as they prepare to cross the street? The answers seems obvious: for the former's red skirt and the latter's green, red and blue clothes. Herzog was so taken by this chromatic relation that he produced another view centered on the two women's legs.

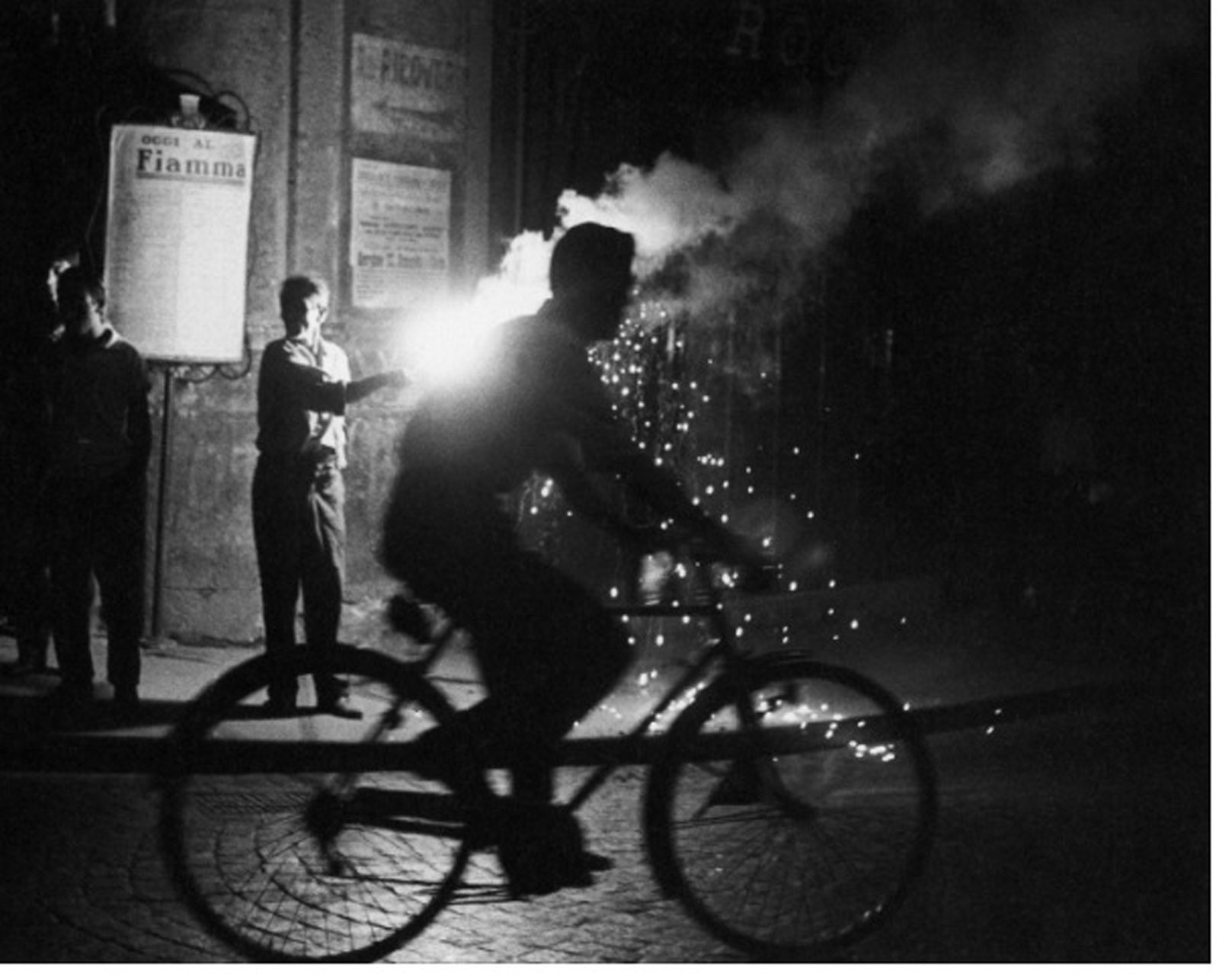

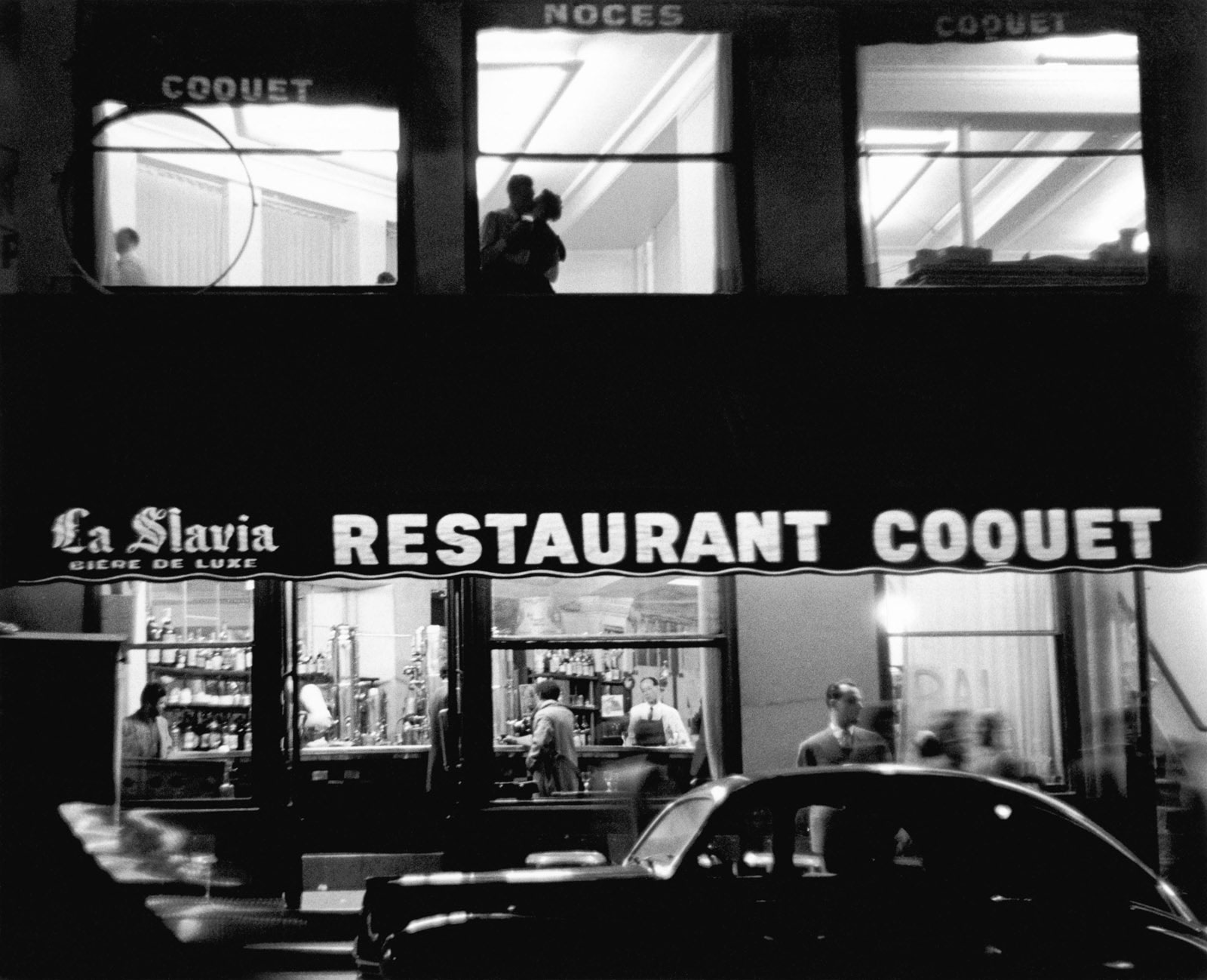

In short, what is striking in Herzog's photos is less the city itself as photography and its possibilities. And the same goes for Weiss too. But whereas Herzog photographs photography's ability to document reality as it presents itself to him, in all its visual complexity and richness of colour, Weiss underscores its power to transform, to reduce reality to a contrast, as borne out in the numerous effects of back-lighting and night views on display in the exhibit. Light is the subject of these images, and the camera's unique ability to capture it, to capture light, which for her is 'a source of magic, of enchantment, of some inexplicable quality of the photo'.

One thing is certain: with Sabine Weiss and Fred Herzog, the city lends its mirror to photography.

Étienne Hatt

[1] Sabine Weiss, Intimes convictions, Contrejour, 1989.

[2] Grant Arnold, 'An Interview with Fred Herzog', in Fred Herzog. Vancouver Photographs, Vancouver Art Gallery/ Douglas & McIntyre, 2007.

[3] Jeff Wall, 'Vancouver Appearing and Not Appearing in Fred Herzog’s Photographs', in Fred Herzog. Photographs, Douglas & McIntyre, 2011