L'épure photographique

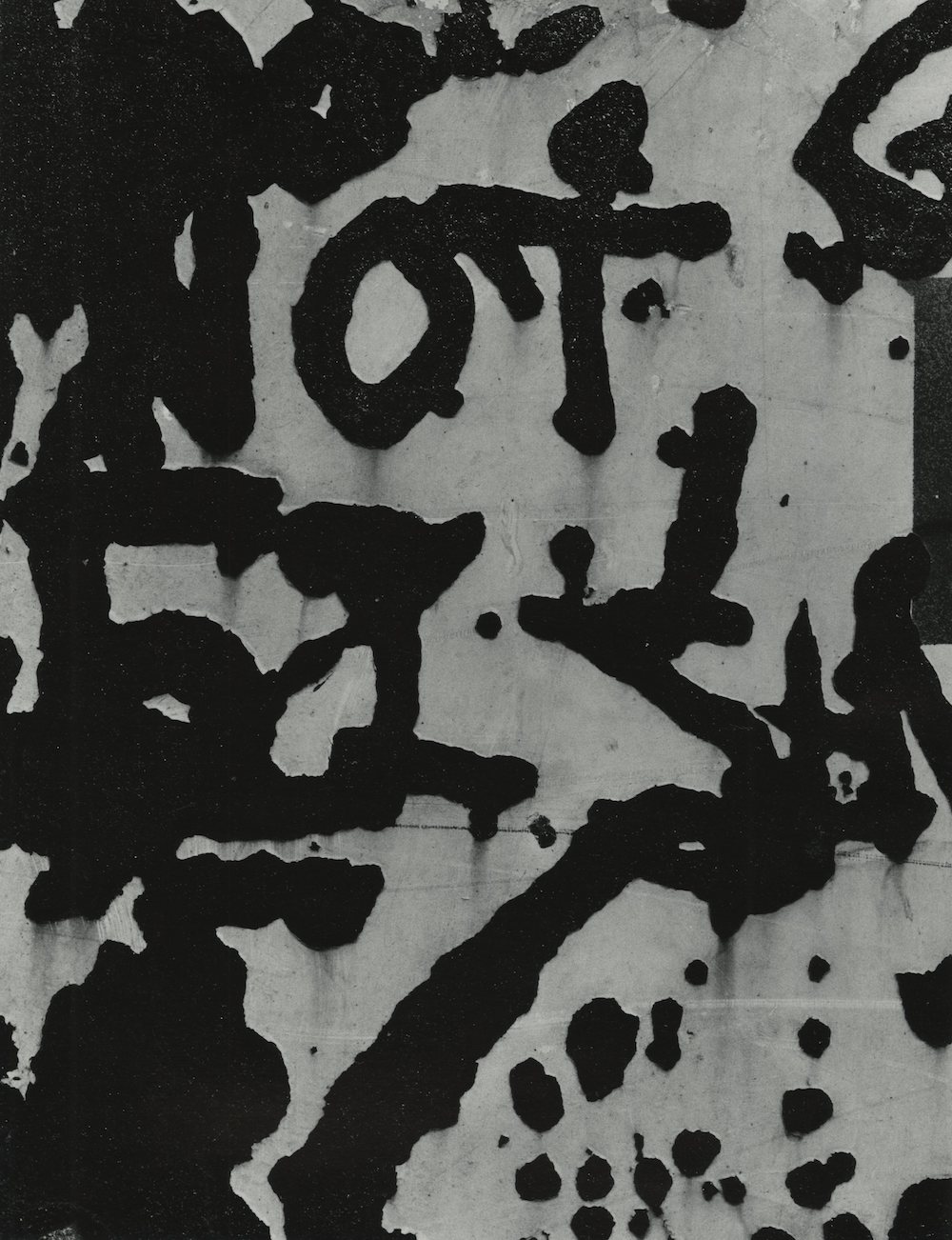

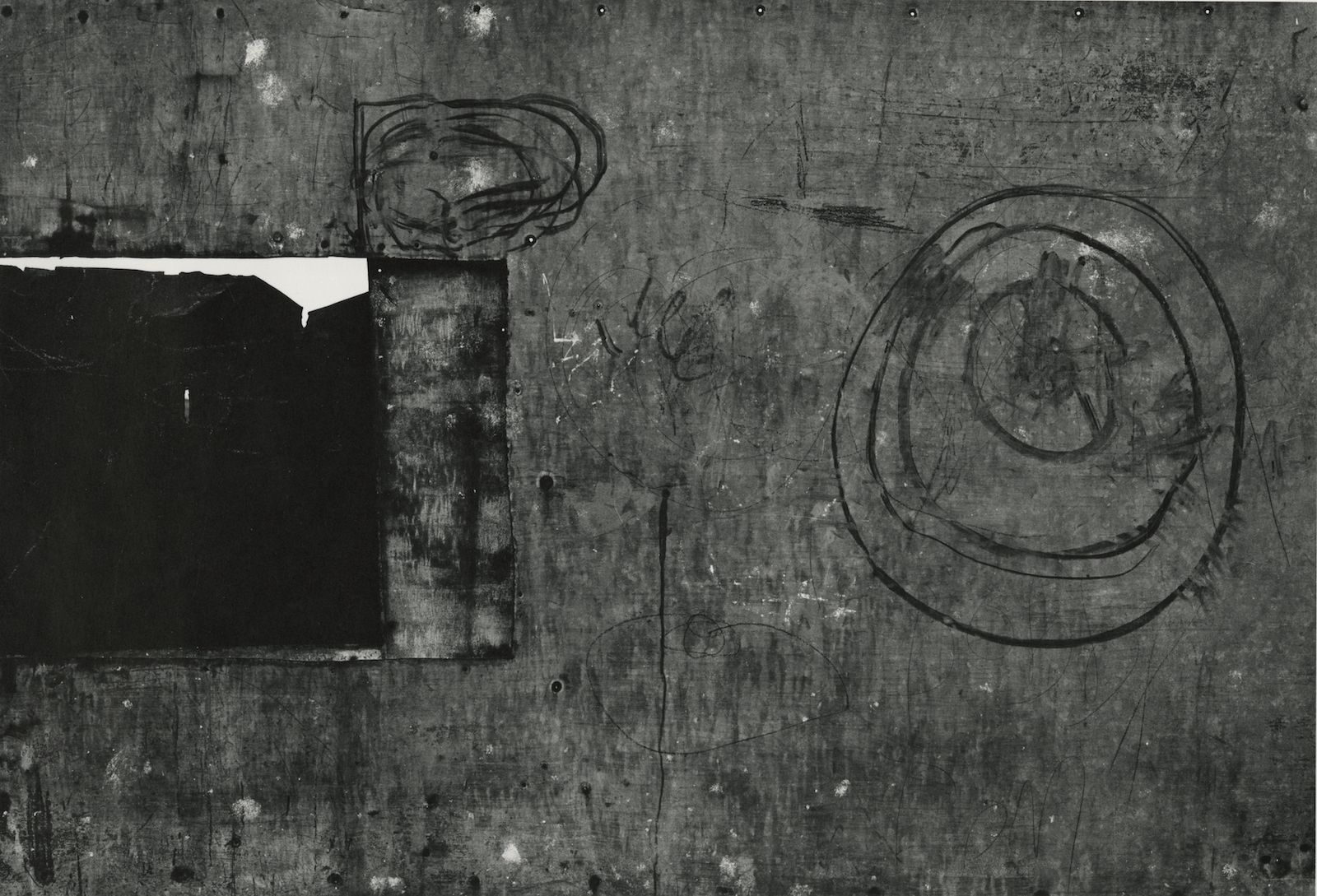

Image: 10 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Annotated, dated and signed by artist on verso

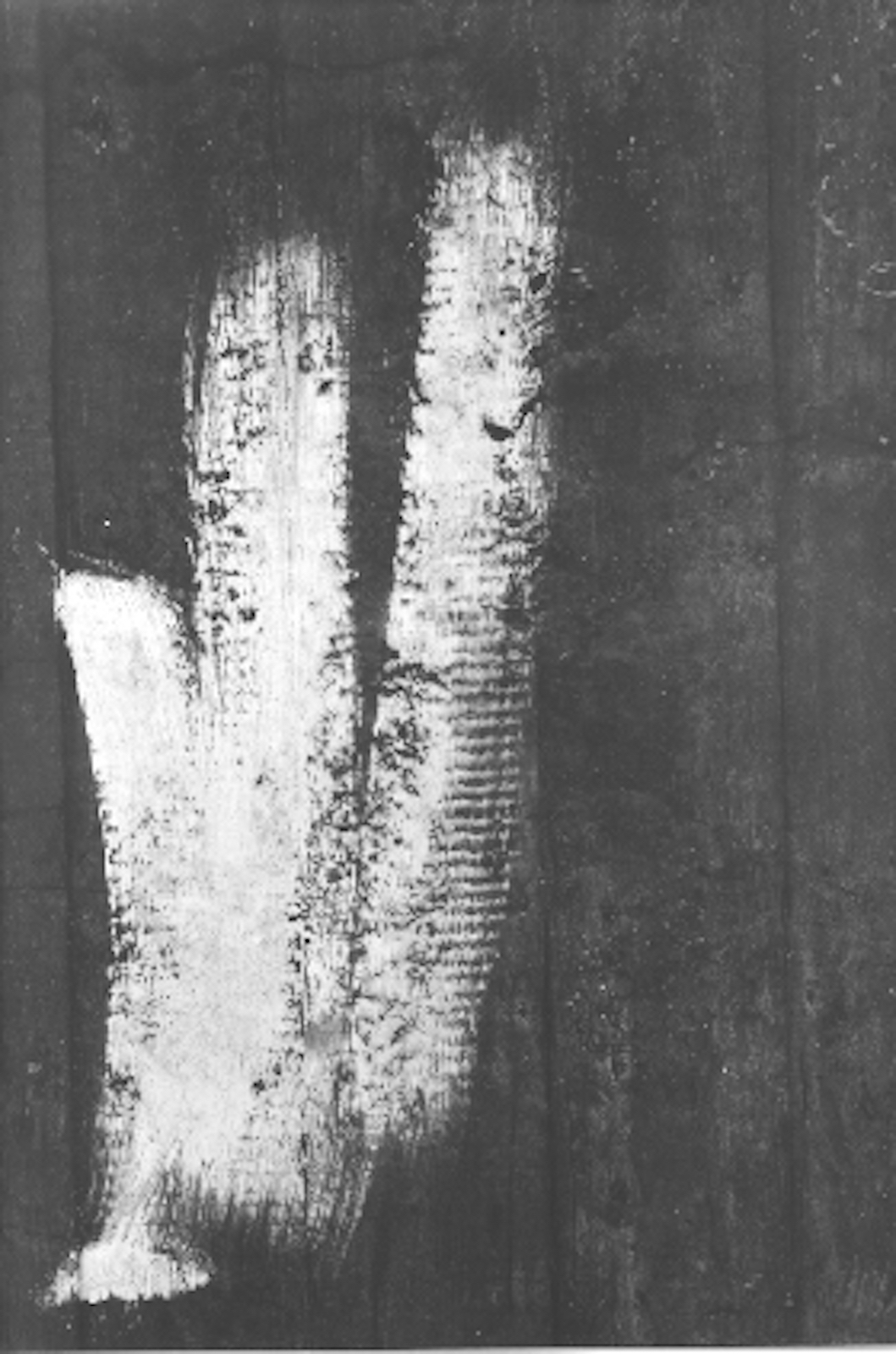

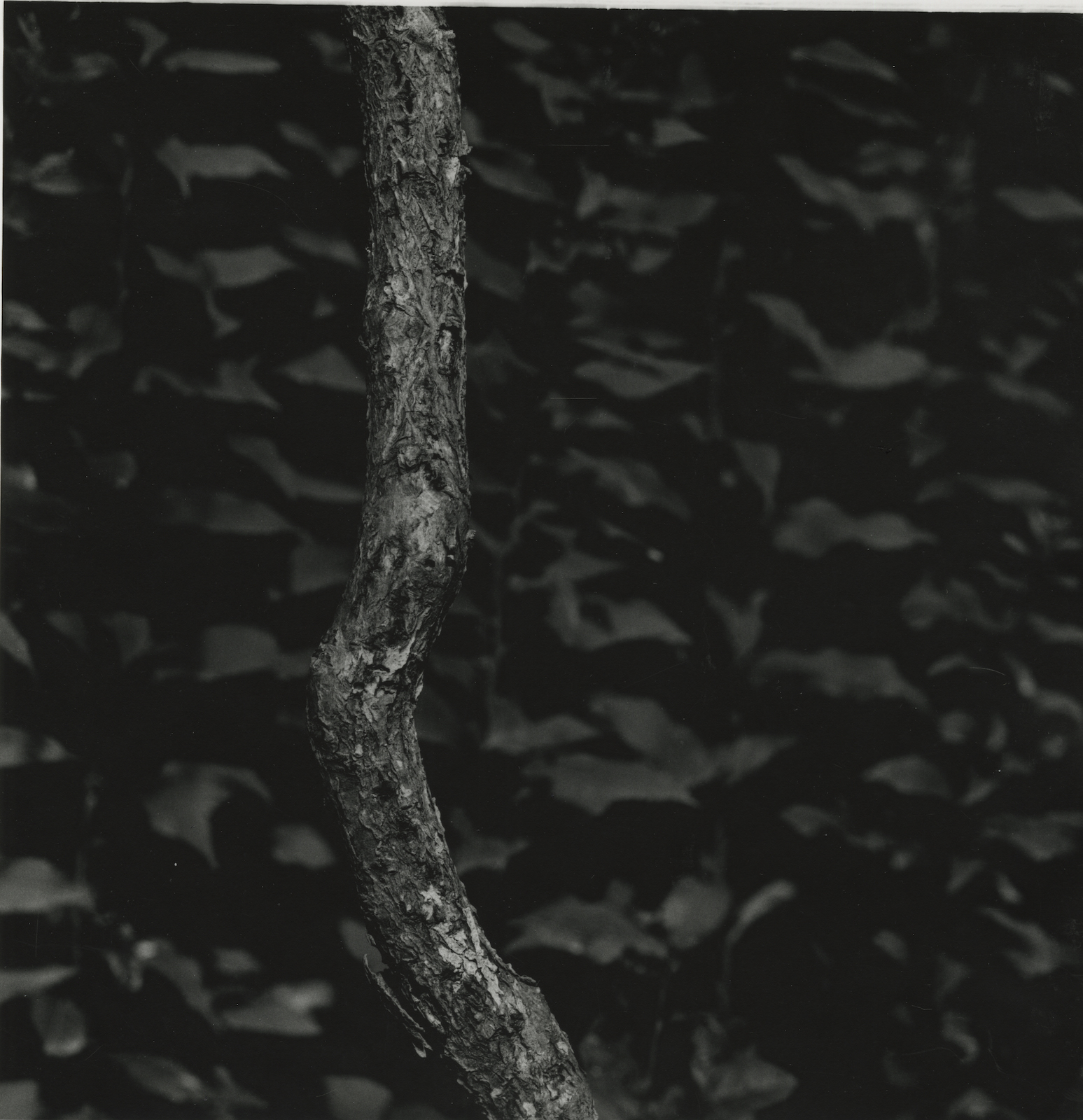

Image: 13 1/16 x 9 13/16 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on verso

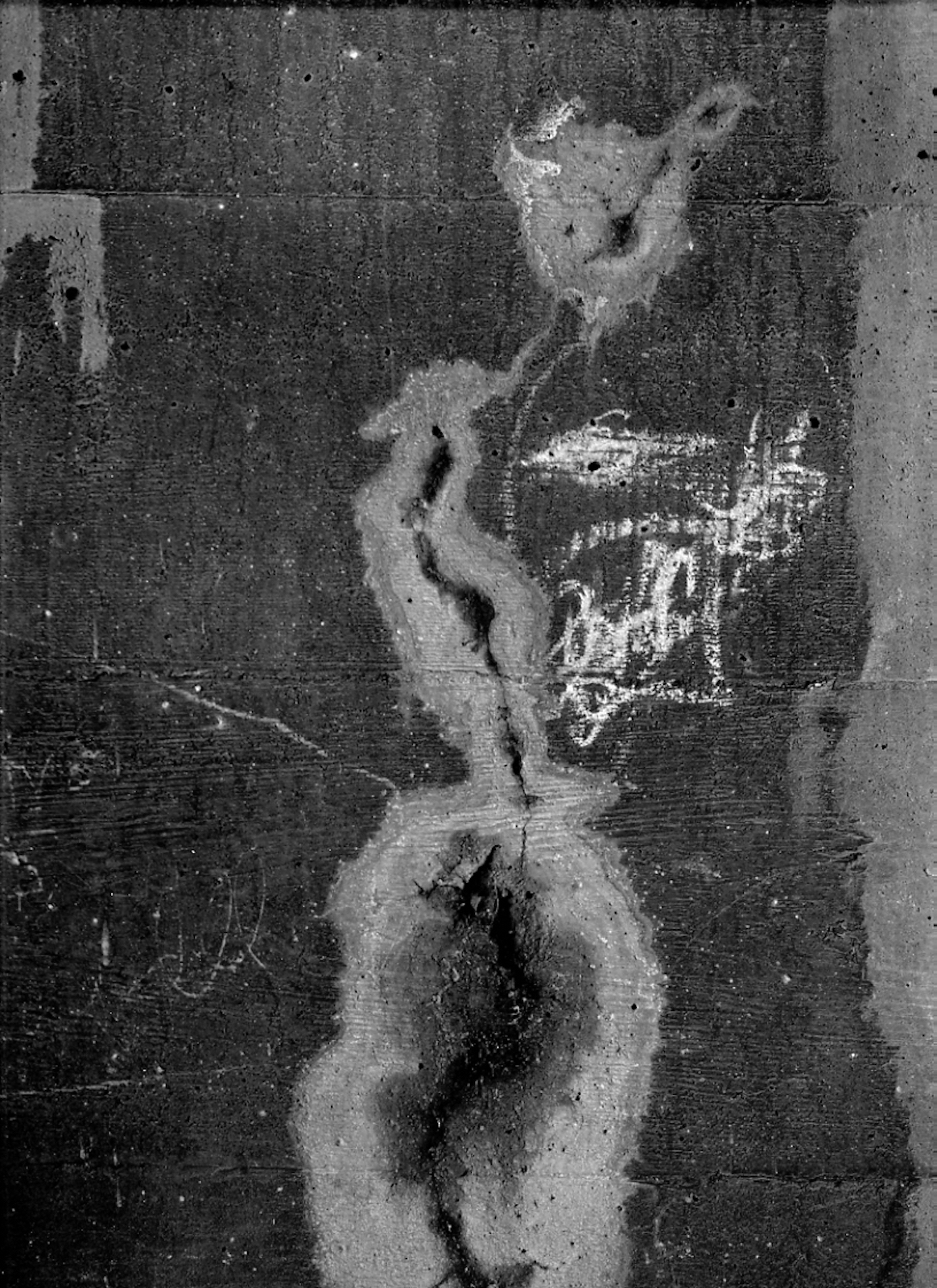

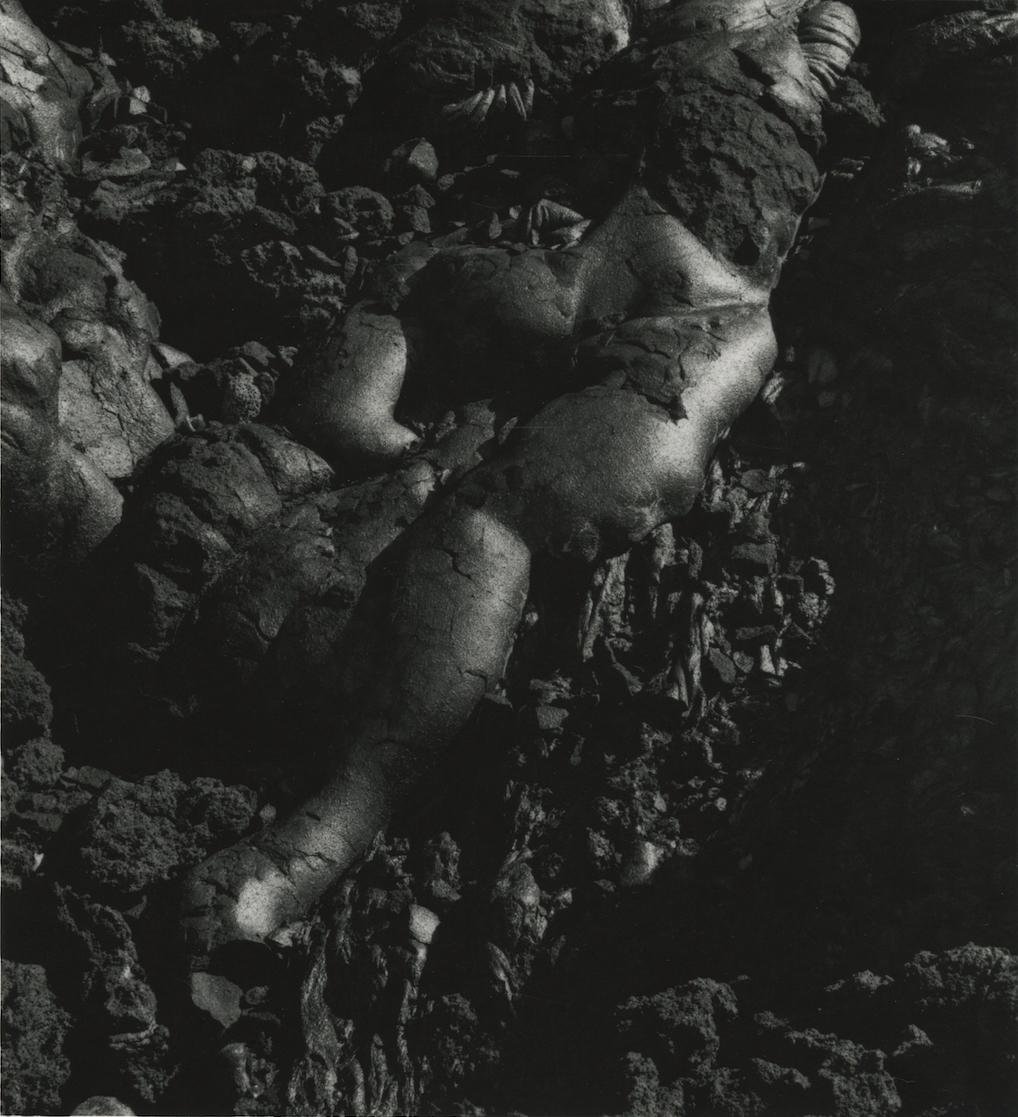

Image: 13 1/4 x 9 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

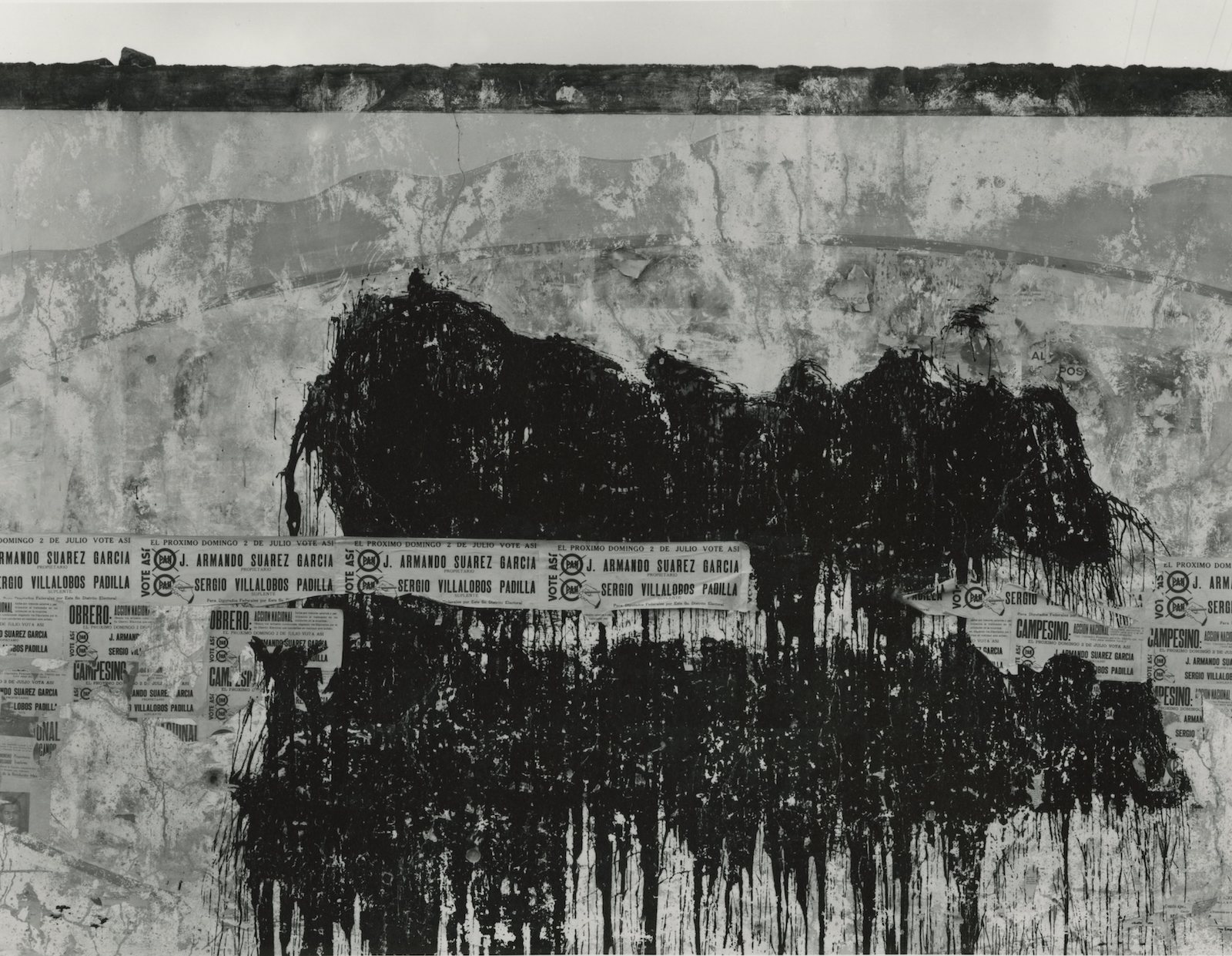

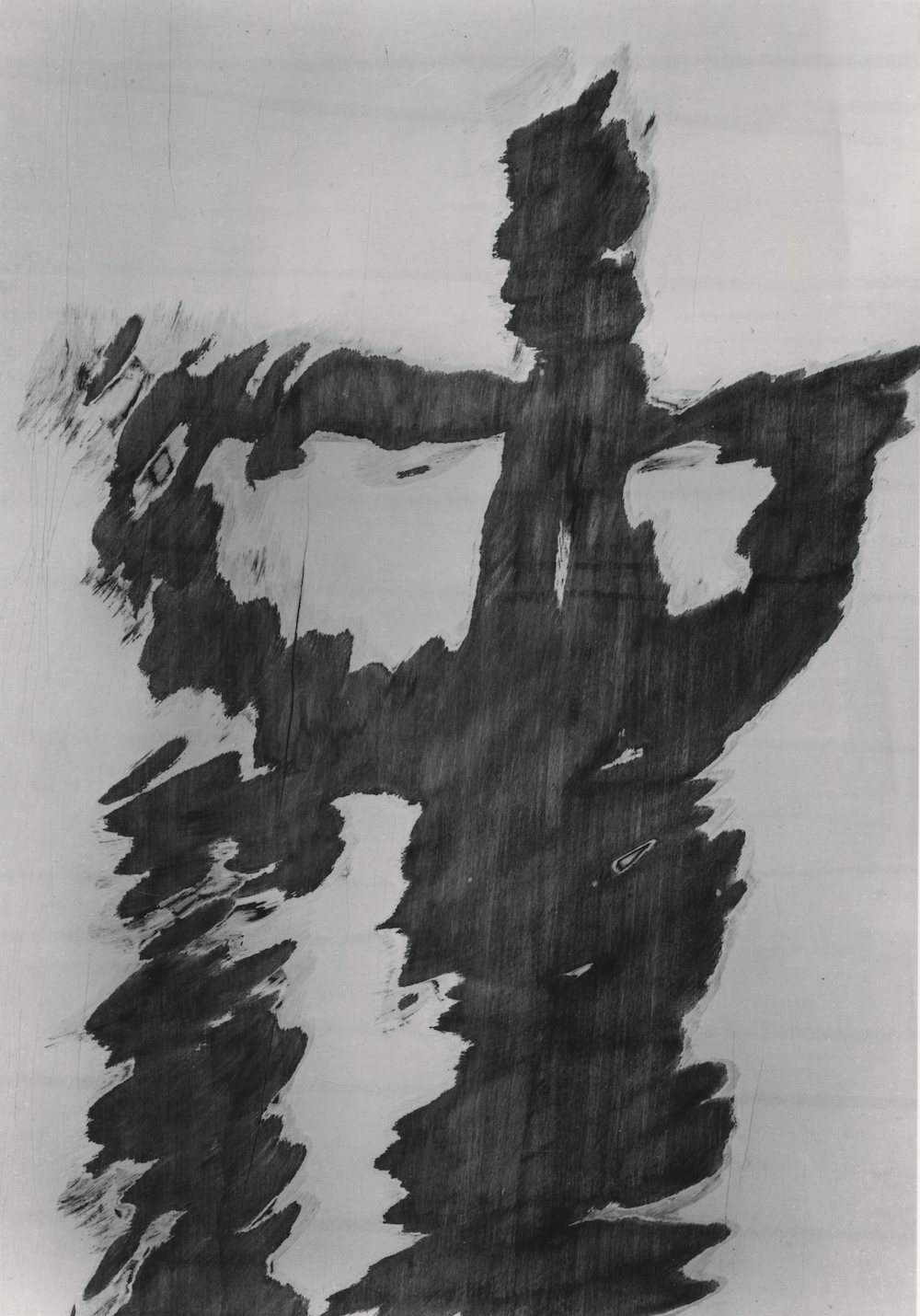

Image: 10 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on verso

Image: 9 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 10 x 13 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 9 3/4 x 13 1/2 inches

Titled and annotated by artist

Image: 8 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on verso

Image: 10 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 10 x 13 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled and dated by artist on verso

Image: 5 x 13 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on verso

Image: 10 3/8 x 13 3/8 inches

Dated and signed by the artist on recto

Image: 13 7/16 x 10 7/16 inches

Titled, annotated and dated by the artist on verso

Image: 10 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 11 5/8 x 9 1/2 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on recto

Image: 10 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 13 x 16 1/2 inches

Print: 14 x 17 inches

Dated on verso

Image: 10 7/16 x 13 7/16 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 10 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 9,6 x 12,7 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on verso

Image: 10 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on verso

Image: 9 x 13 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 10 1/162 x 13 3/8 inches

Dated and signed by the artist on recto

Image: 10 x 10 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Annotated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 9 x 9,7 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on recto

Image: 12 3/4 x 18 1/2 inches

Dated on verso

Image: 8,5 x 9,7 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 9 x 13 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 7 x 12 1/2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by artist on verso

Image: 9 x 13 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 10 3/8 x 13 7/16 inches

Anotated on verso

Image: 12 x 9 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 9 x 10 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, date and signed by artist on recto

Image: 10 x 10 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 10 x 13 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Dated on verso

Image: 10 x 13 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Dated by artist on verso

Image: 10,5 x 13,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Dated on verso by artist

Image: 5,70 x 8 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Annotated, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 5,4 x 7,7 inches

Print: 8 x 10 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 7 7/16 x 8 11/16 inches

Titled, annotated and signed by the artist on verso

Presentation

Opening on Saturday, october 27th, from 2 to 7 pm

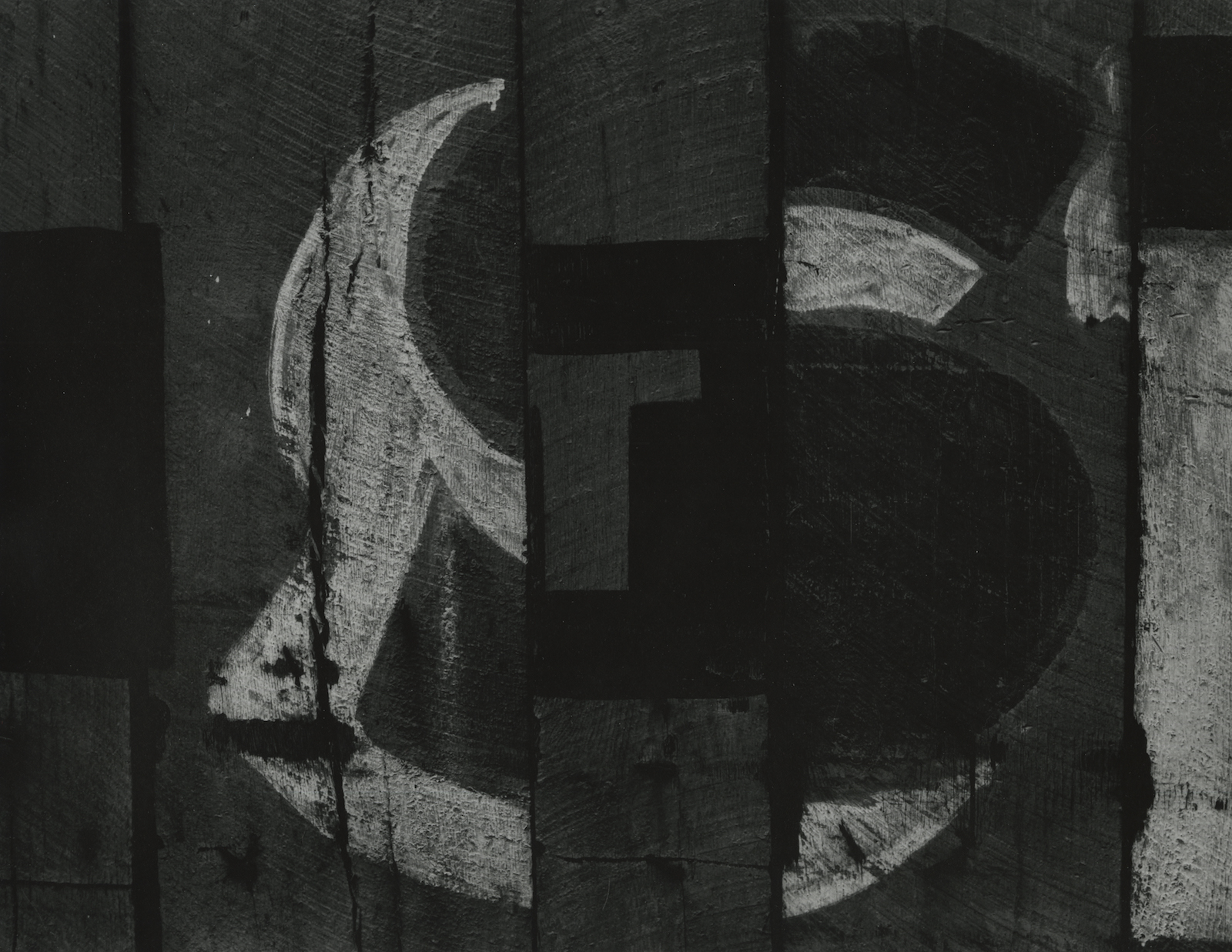

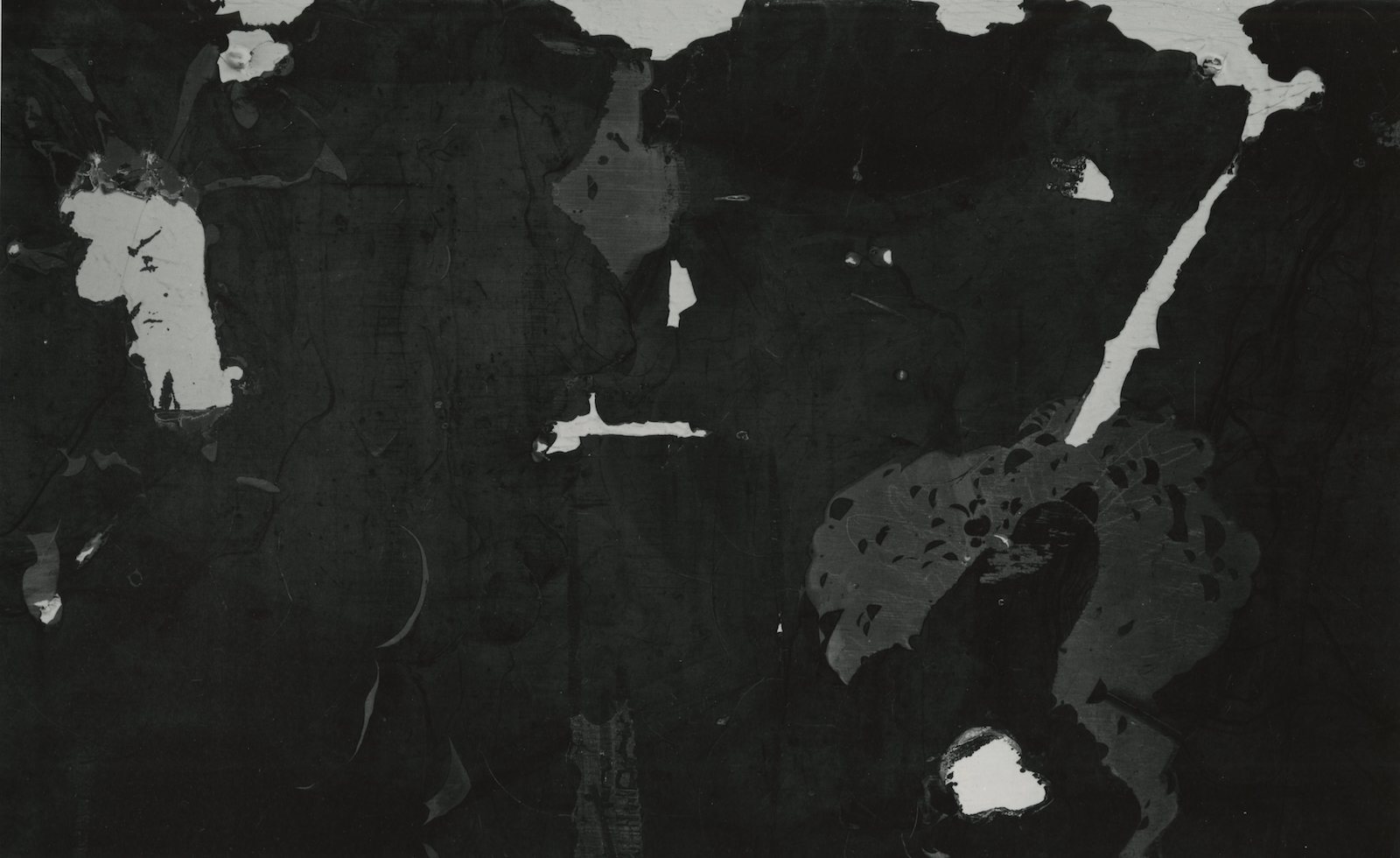

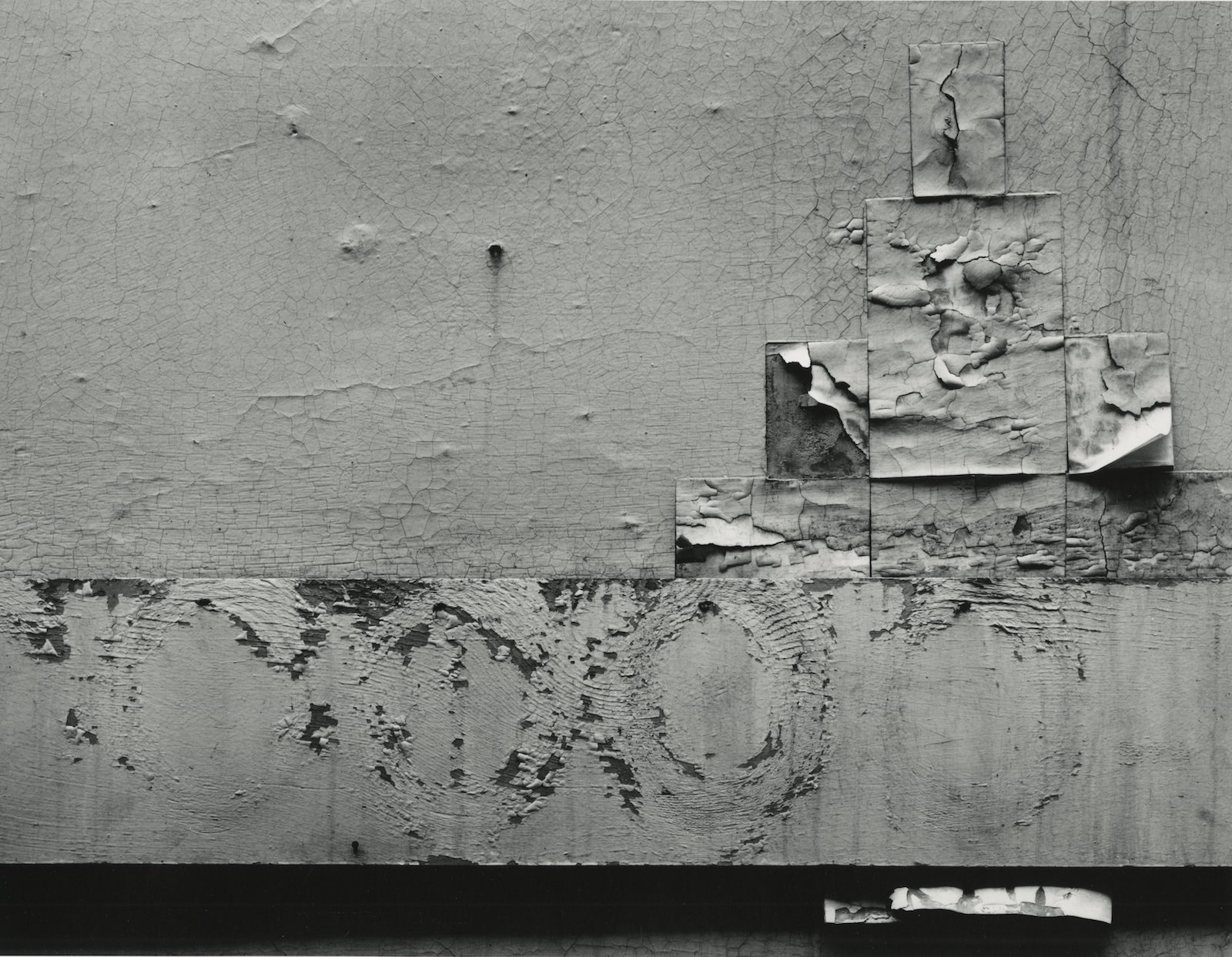

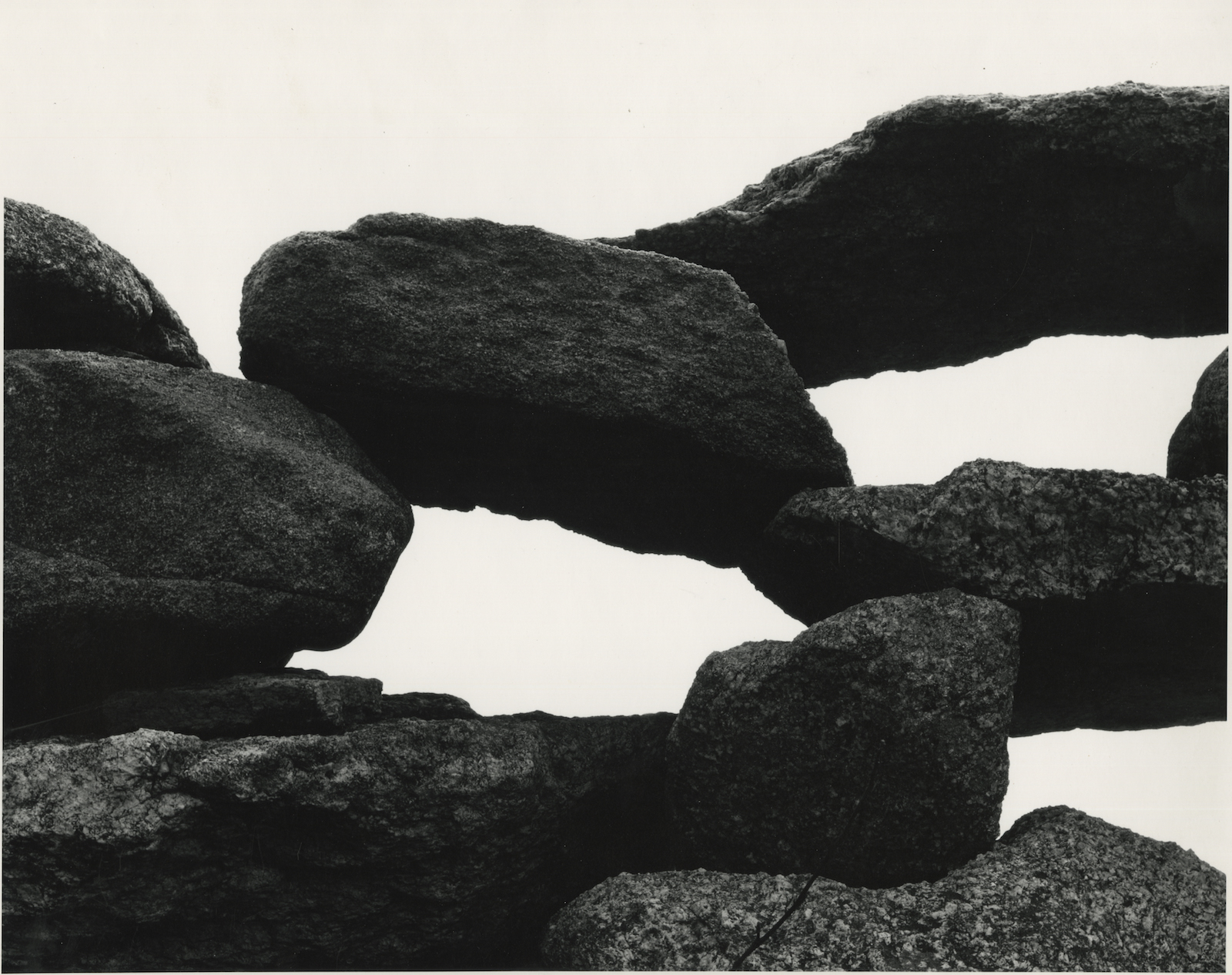

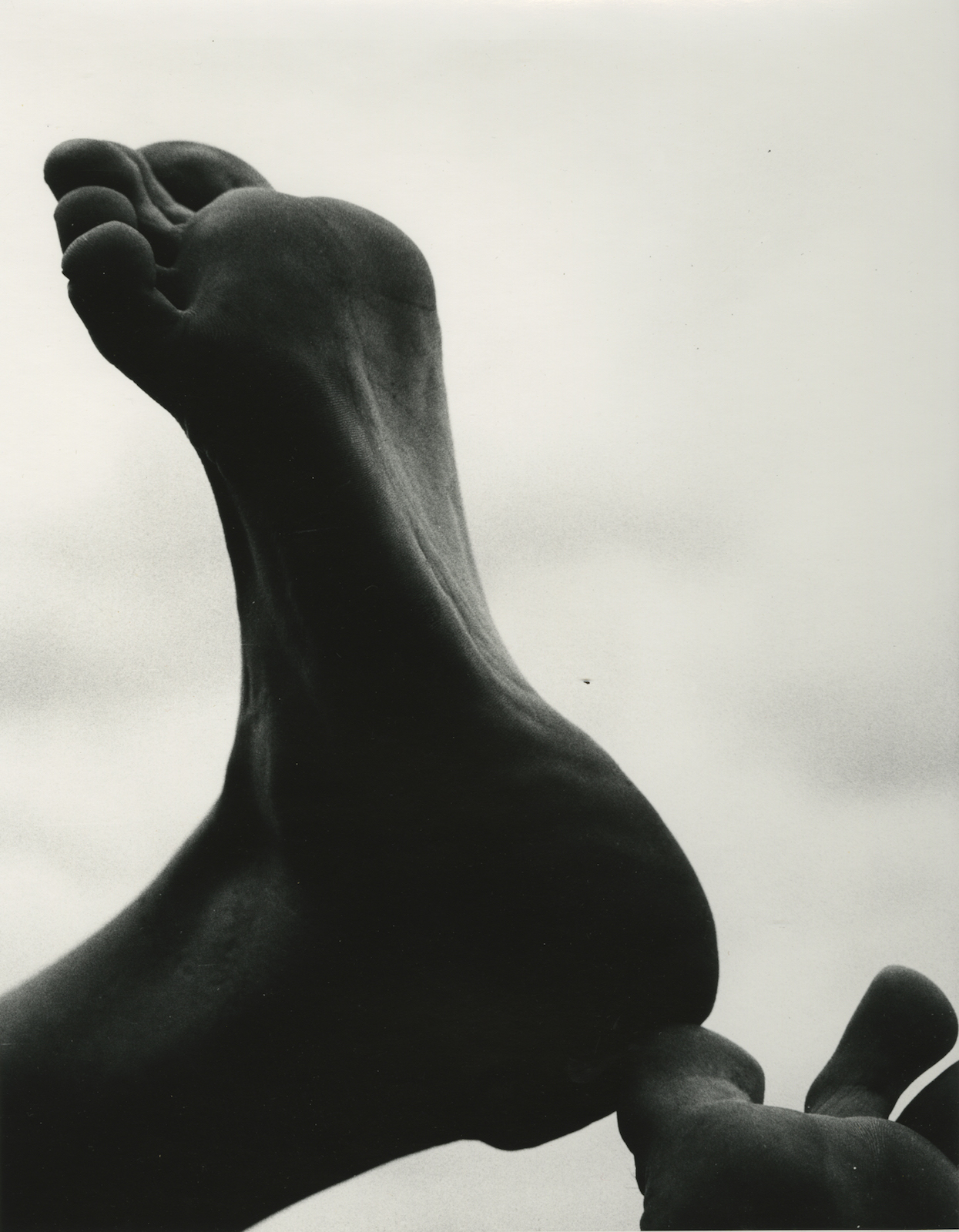

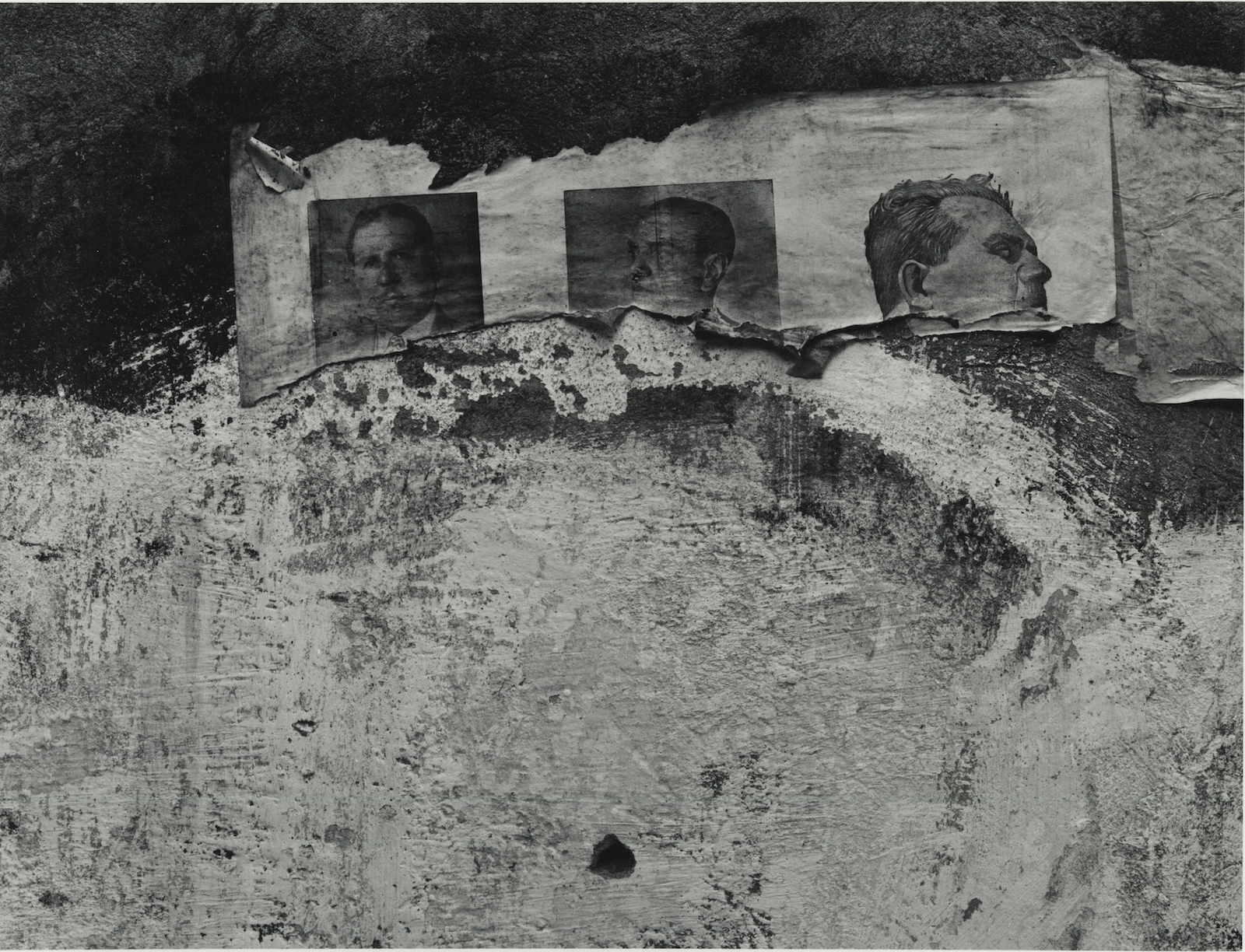

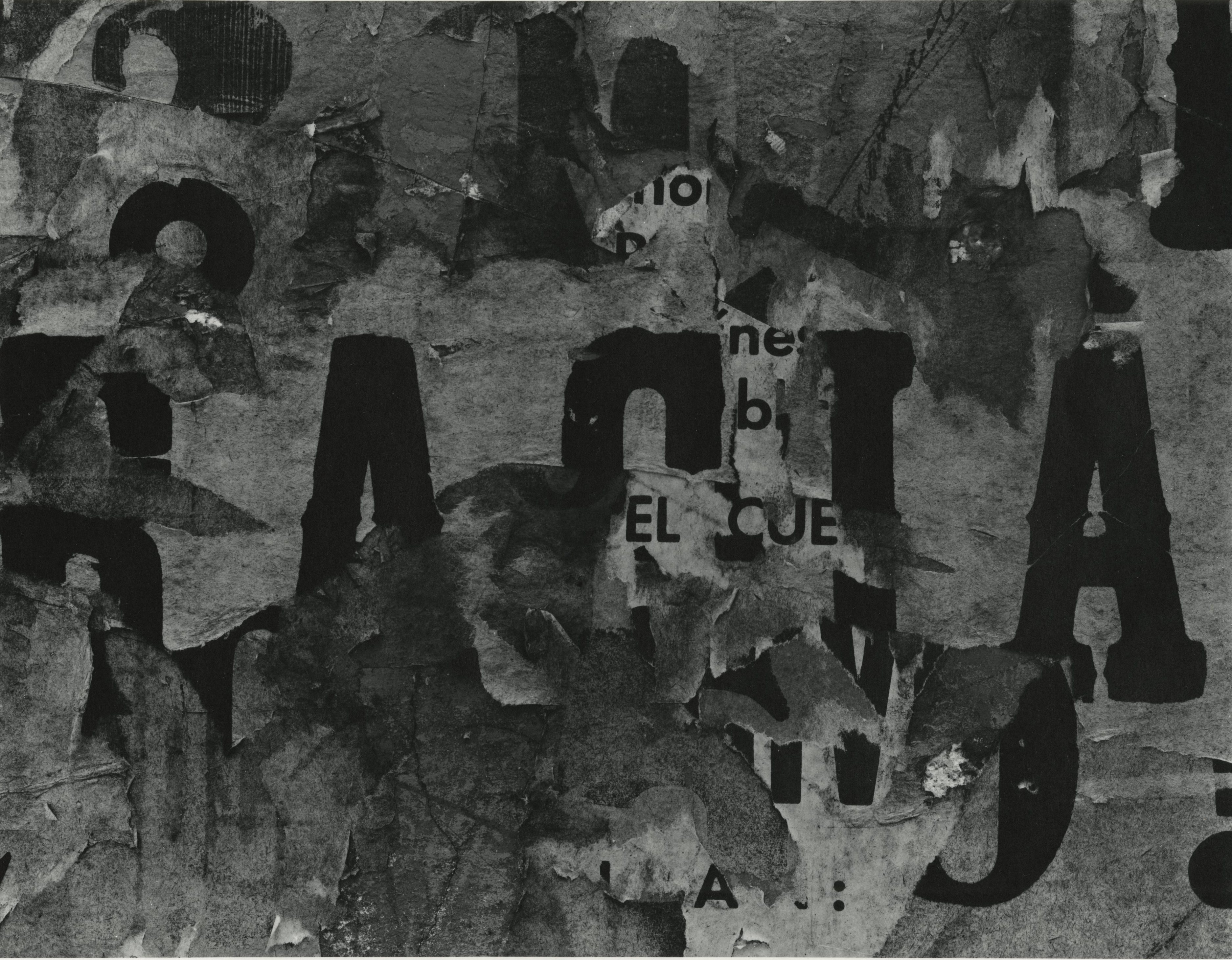

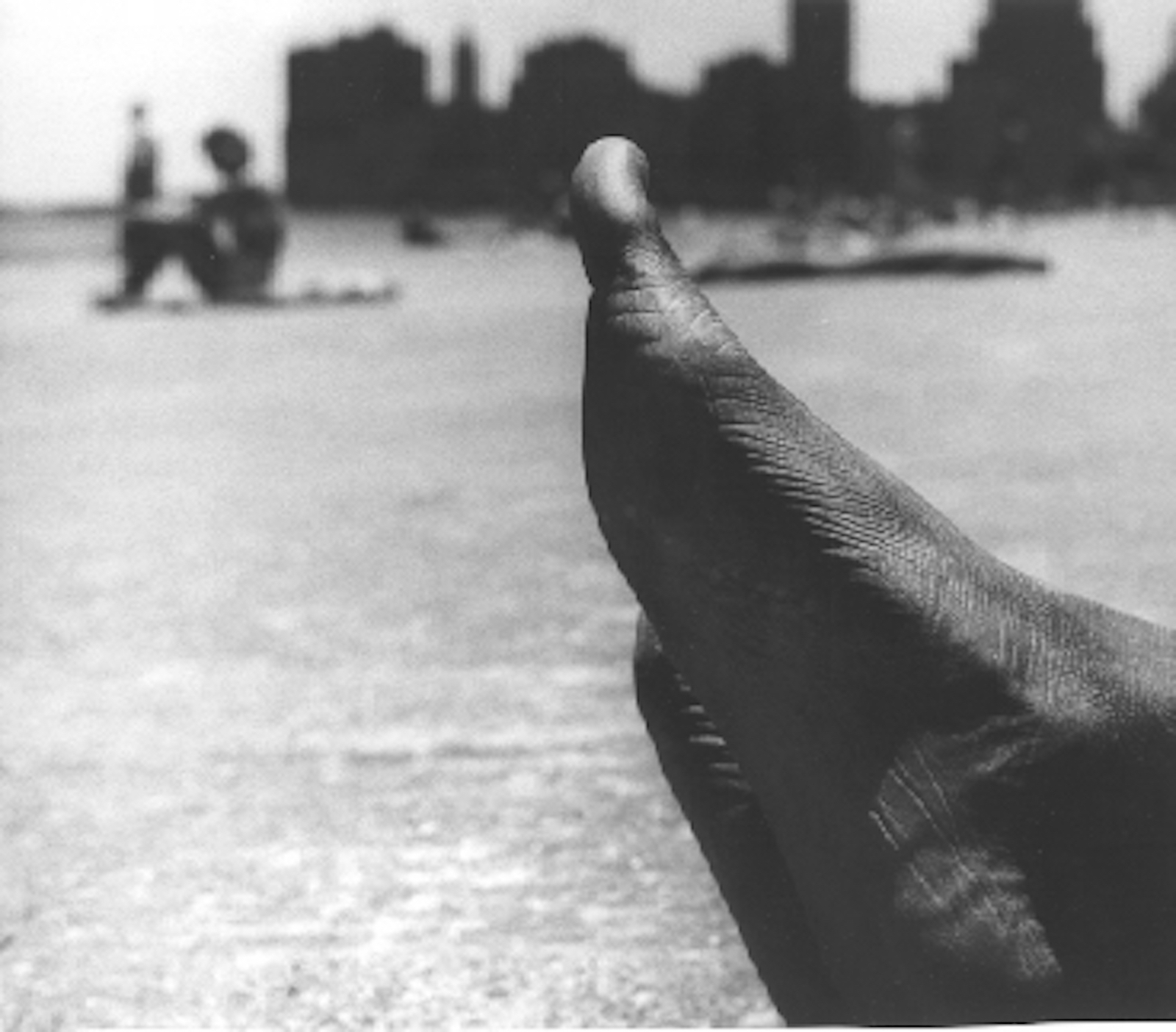

Aaron Siskind (1903-1991)'s work cannot be reduced to a single photographic genre. Alongside his remarkable career as a teacher who put a stamp on several generations of photographers, this great figure in the history of American photography never ceased to surprise. From his very documentary vision with the Photo League to his much more plastic endeavours linked to abstract, expressionist painters, his approach to photography embraced different styles and ruffled numerous prejudices.

PRESS RELEASE

Aaron Siskind’s towering presence in the landscape of twentieth-century American photography rises from two foundations of accomplishment and influence — his art and his teaching. Beginning in the early 1930s and continuing until his death at eighty-seven in 1991, his copious production of varied and highly creative images created a legacy of original vision which eventually obliterated whatever line might still have seemed to segregate photography and painting in the 1940s and 1950s. While he is often compared to such Abstract Expressionist painters as Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman and Franz Kline, with whom he was good friends, the records show that Siskind’s photographs had as much influence on their work as theirs had on his. Siskind's manner of zooming in on visual details and fragments in ways that explored gesture and shape but that had little to do with the nominal subject matter in front of the camera clearly made him a brother in the family of Abstract Expressionists. (…)

Siskind was born on 4 December 1903 in New York into a family of Russian Jewish immigrants. (…) Finding his home life unexciting, Siskind spent much of his youth roaming the streets, responding to the intellectual and social stimulation he found there. His devotion to beauty, discovery and expression marked him as an artist from the beginning, although, at first, words were his medium. The socialist ideals of justice and equality appealed to him j as did the many sidewalk speakers espousing them from soapboxes on upper Broadway. By the age of twelve Siskind had his own soapbox and was attracting a regular audience. (…)

As a wedding present for his first marriage, Siskind was given a camera. He experimented with it during a honeymoon on Bermuda and found he enjoyed it. By 1932 he had purchased a better camera and joined the Film and Photo League in New York City, one of the most influential of the numerous camera clubs in the United States. (…) The habits of working he developed doing documentary photography — keeping everything in sharp focus and shooting from a simple point of view — never left him. ‘I have remained very true to my documentary training: he recalled in a 1963 interview. By this he meant that he retained 'tremendous faith in the thing itself' . Whatever metaphoric or symbolic energy his images might release, objects in his photographs such as rocks or peeling paint, remained recognizable objects in the real world. (…)

Undeterred, Siskind continued on his own path, and in the summer of 1943 in the fishing village of Gloucester, Massachusetts he had what he called 'a picture experience' an epiphany that changed the course of his work for ever. Instead of working from a programme, as he had done on documentary projects, he devoted himself to something that he had already sensed was important — letting objects speak for themselves in their own way. (…)

In Gloucester Siskind went a step further: he began without any conscious ideas that he would then have to forget in order to photograph in this new way. Instead he substituted the discipline of a fixed working routine that had nothing to do with the things he would photograph. Each morning he walked out with twelve sheets of film, enough to make six pictures, two exposures for each. He worked within a very small area, covering no more than a single wharf or block of the village. When he printed the photographs that winter, he saw something unexpected. In an interview in 1963, he recalled those moments: 'To put it on a higher expressive plane: there was, in a sense a revelation to me. I made some pictures and these pictures revealed meaning to me, a way of making a picture which I had never dreamed of before. Well, when that happens to you, you've just got to follow.' 'I didn't push photography,' he said, 'photography, in a sense, led me.'

Siskind saw how he could move fully from the sphere of description to the plane of ideas in abstracted form. He saw in what he had done — framing organic objects within strong geometric compositions — a reflection of a basic duality he had long puzzled over. 'In the pictures you have the object,' Siskind continued in the 1963 interview, 'but you have in the object or superimposed on it, a thing I would call the "image" which contains my idea. And these things are present at one and the same time. And there's a conflict, a tension. The object is there, and yet it's not an object. It's something else. It has meaning, and the meaning is partly the object's meaning, but mostly my meaning.'

It has been argued that photography emerged as an inevitable result of the long quest in the visual arts to achieve single-point, three-dimensional perspective within the two dimensions of a flat picture plane. Ironically, Siskind had discovered that his growth as an artist demanded that he discard this hallmark of photographic technology. In the ‘flat, unyielding space' of the perspectiveless picture plane, as he described it in ‘The Drama of Objects', he could represent his 'deep need for order'. Here, objects 'cannot escape back into the depth of perspective. The four edges of the rectangular [space] are absolute bounds. There is only the drama of the objects, and you, watching.'

In 1945 and for many years afterwards, Siskind's photographs seemed a radical departure from his documentary work, having more to do with painting than photography. Speaking to the History of Photography class at Columbia College in Chicago in 1982, Siskind recalled that, 'for a long time [Garry] Winogrand went around saying, "Siskind isn't a photographer — he's something else.“ ’ With a chuckle, he added, 'He's stopped doing that.' Reflecting on his place in photography's history in the 1985 videotaped interview previously mentioned, Siskind said that, 'In the course of the history of photography we were [in the 1930s and 1940s] at a period when people were emphasizing the sociological and psychological and things like that, but there was a time before when they made pictures which were metaphors, symbols.' He did not see himself as being revolutionary: 'It was just that I brought some elements of the past forward,' he said.

Aaron Siskind, James Rhem ; 55 Collection, Phaidon, 2003