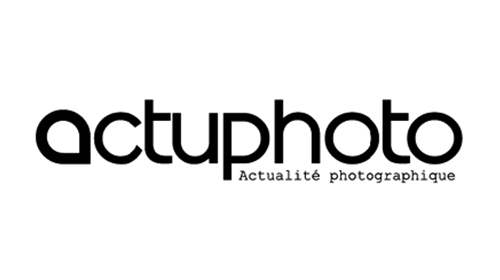

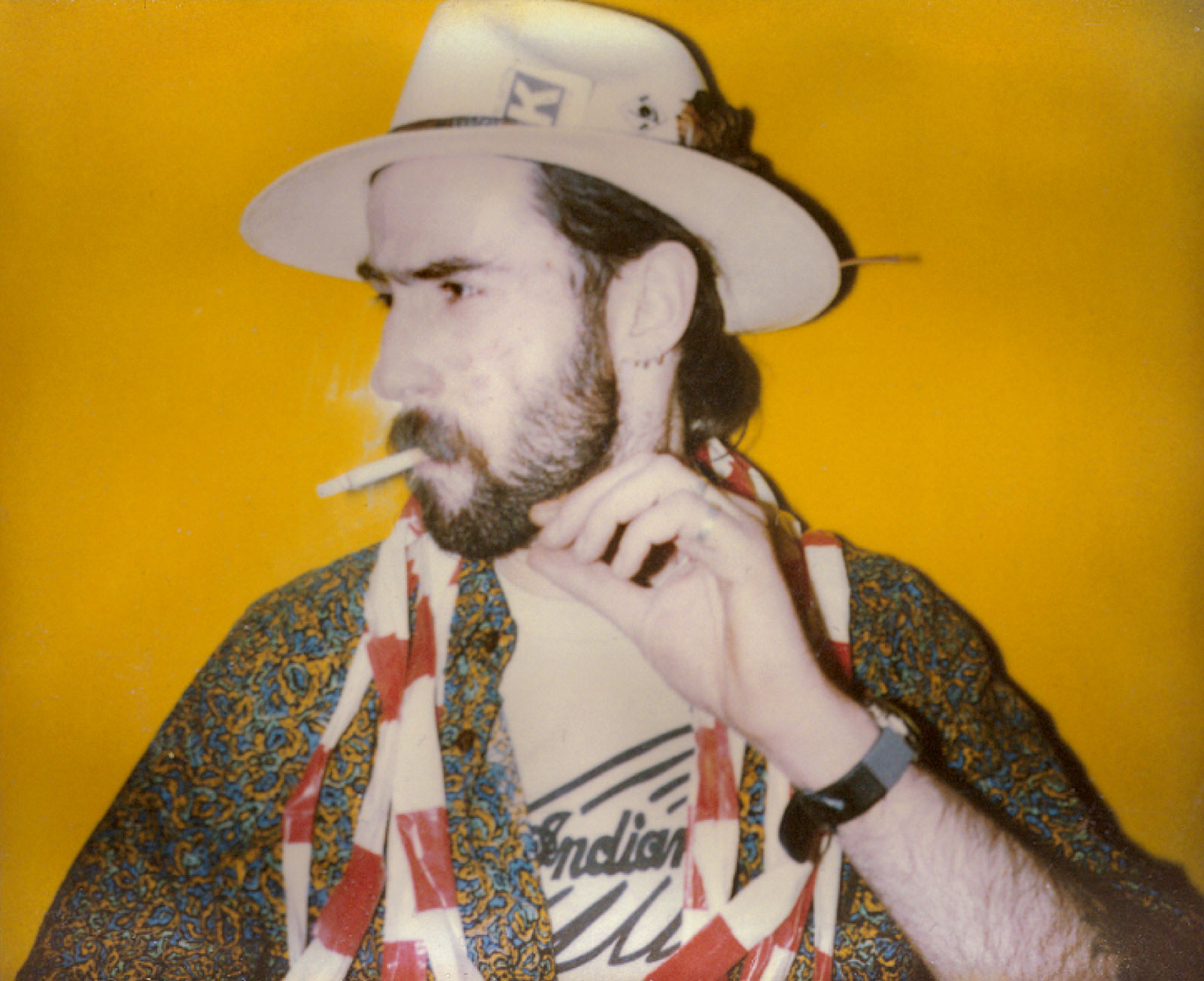

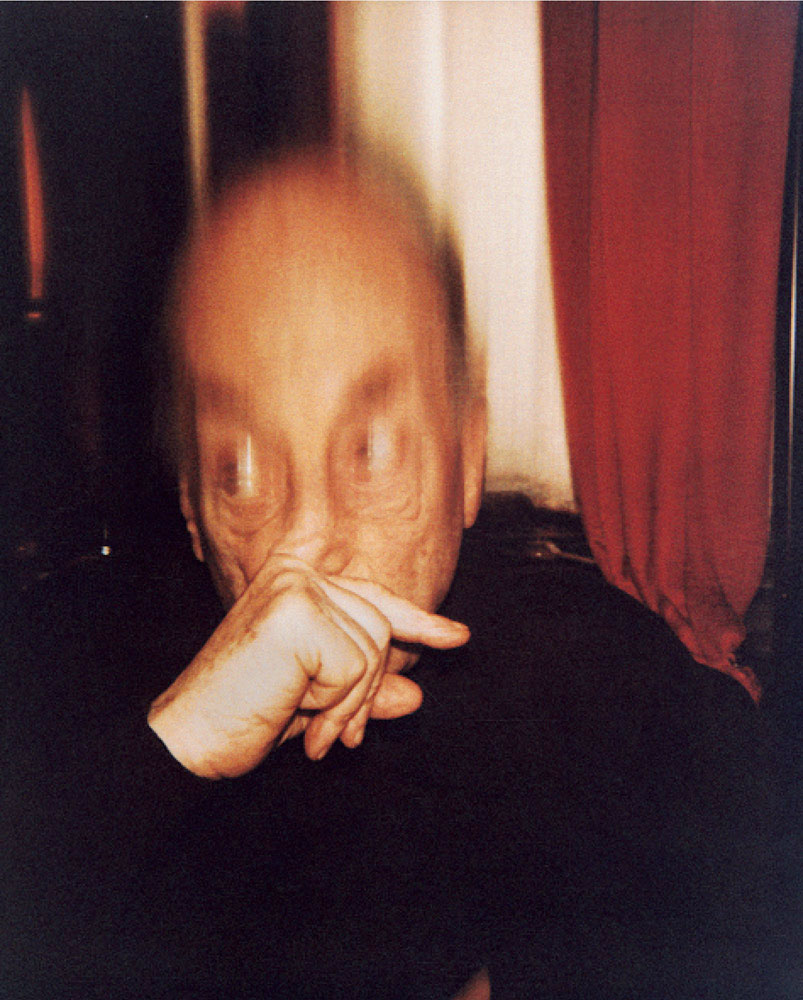

Rodolf Hervé

![Fekete Lyuk [Black Hole], night club, Budapest, 1990](/cspdocs/artwork/images/LDLG_000995.jpg)

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. RH0803014 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. RH0803024 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. RH0803025 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. RH0803033 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. RH0803003 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. RH0803009 Kindly.

Presentation

Dazzling. That's the first word that comes to mind when one thinks of Rodolf Hervé (1957-2000). Dazzling due to the relative brevity of his existence. And especially dazzling in regard to his work. Back at a time?mid-1980s to mid-1990s?when digital photography didn't yet exist, it wasn't by trivial chance that Rodolf Hervé chose the Polaroïd. Out of urgency. Urgency to appropriate and transform his space. Polaroïd on which he could act as a painter on his canvas. For Rodolf Hervé was just as much a painter, musician, or video-maker as a photographer.

Press

Texts

FULGURANCE

Dazzling. That's the first word that comes to mind when one thinks of Rodolf Hervé (1957-2000). Dazzling due to the relative brevity of his existence. And especially dazzling in regard to his work. Back at a time?mid-1980s to mid-1990s?when digital photography didn't yet exist, it wasn't by trivial chance that Rodolf Hervé chose the Polaroïd. Out of urgency. Urgency to appropriate and transform his space. Polaroïd on which he could act as a painter on his canvas. For Rodolf Hervé was just as much a painter, musician, or video-maker as a photographer. There's also another reason that justifies his use or the Polaroïd, as he explained in a text that appeared in Hungary in 1991: "Being the only son of Lucien Hervé, I followed in his wake, in collaboration with him, through him... And although through several of my works I had already liberated myself from the statue of the Commendatore it's worth mentioning to what degree the Polaroïd helped me break with the paternal style (to the point of damning house spirit)." In Rodolf Hervé the individual and the work are closely tied. Infinite violence and infinite tenderness. A body of work amazingly built, a body of work amazingly broken. Unique work that couldn't be related to any other. All due to his culture, at the same time man of Enlightenment and notable figure in the underground, fascinated by Surrealism and by Constructivism. If he scratches and deforms reality, it's because reality wounds him and drives him to deform himself. In an interview in the Hungarian magazine "Kurir" in 1991, Rodolf Hervé made very clear his vision of photography: "I don't want to tell anything with my photographs, I fight against the anecdotal. I just try to make them successes. They perhaps aren't beautiful, but what's beautiful isn't necessarily good. I try to take photographs that are true". And in that same interview he concluded in answer to a question about depression: "I like being sad, I like being happy. I am not categorically sad, although I like depression, for it's like a wave, after the depths comes the crest." When people complimented Schubert for "Death and the Maiden", he would answer back: "No matter how extended my musical knowledge, I couldn't have written that piece because I've expressed my sadness therein... in my case I learned early on that infinity, eternity don't exist. Men disappear for different reasons, because they die or because they go away. While the world gets bigger, it doesn't cease to get smaller. Eternity is what I'm now living, it is just there where I am at this moment... " The "Polas" by Rodolf Hervé ? he said Pola ? reverberate like gunshot in the middle of a celebration.

Olivier Beer

Far from well known and having disappeared long before able to aspire to true recognition during his lifetime, Rudolf Hervé is one of those artists who, to paraphrase Bergson, belongs to the future. This series of Polaroids, taken between 1986 and 1993 is a veritable manifesto. Twisting, swelling, superimposing, scratching?all those means of notation are at the disposal of a quest: to abandon the figurative, reveal presences, forces, that go beyond representation. Free of all constraint and turned completely towards an incarnation of thought in action, this way of apprehending the visible makes Rodolf Hervé astoundingly modern and seems to throw new light on a whole area of photography over the past ten years. Simultaneously hallucinatory, verging on surrealism and conceptual, this body of work seems to me to be premonitory of all of the problematics of contemporary photography. For today, photography is undergoing an unprecedented mutation. Whereas the visible universe is almost entirely documented, contemporary photography invents postures, trajectories between reality and fiction. It is becoming a fluctuating medium that artists each take on in their own way. In rereading Rodolf Hervé's photographs, we experience almost physically that urgency to prove, to provoke sensations, to experiment with life in all its aspects, to take on one's own body as the first experimenting ground. It is just this that is echoed in Bacon's phrase (as quoted by Deleuze): « rapportée au corps, la sensation cesse d'être représentative, elle devient réelle » (in regard to the body, sensation ceases to be representative, and becomes real).

Stéphane Couturier

ON THE GROUND

Rodolf Hervé spent the early 1990s living and working in Budapest where he felt he belonged, in a society that had lost its bearings after the fall of Communism and had to start from scratch. The future was completely unpredictable. What has happened since is unfortunately another story! Rodolf Hervé had a habit of turning things upside down, but in Paris at that time, the world had become rigid and materialistic. It was in Budapest he felt the most free. In all his pictures ? maybe I should use the word "images" here, as in holy images, except that these would be unholy images ? one gets a sense of partying, even though desperation is never far away. We should remind ourselves when viewing these pictures that they pre-date those of Martin Parr or Antoine d'Agata. The pictures seem to emerge rather than appear. They reveal a meteor unable to halt its journey. Even though Rodolf was particularly fond of Lautréamont, he reminds me of Rimbaud and I read every one of his pictures as if it were a poem. His work is never superficial; it is corrosive and passionate ? as well as festive and funny. The subject matter is serious but not taken seriously. Rodolf Hervé knew where he came from and had a rich cultural background. He was a child of Auschwitz, a child of Communism, a child of art. But at the same time, Rodolf knew he was going nowhere and he was going there fast. Too fast. This incandescent outburst is what's left of him.

Olivier Beer

Exhibitions

Paris Photo 2018

Group show

8 - 11 November 2018

Soon Art Fair

Group show

11 - 13 December 2015

On the Ground

January 21 - March 5 2015

Soon Art Fair

Group show

11 - 14 December 2014

Autoportraits

Group show

November 7 2014 - January 10 2015

Portfolios #3

Group show

September 16 - October 29 2011

Fulgurance

April 11 - June 5 2008

News

Expérience Photographique

February 13 - April 12 2018