New York

Image: 8 x 12 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 8 x 12 inches

Print: 12 x 16 inches INV Nbr. SW1502025 Kindly.

Print: 7,6 x 11,5 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,6 x 11,5 inches INV Nbr. SW1502004 Kindly.

Print: 9,5 x 11,8 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 9,5 x 11,8 inches INV Nbr. SW1502013 Kindly.

Print: 7,9 x 11,5 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,9 x 11,5 inches INV Nbr. SW1502012 Kindly.

Image: 8,2 x 11,2 inches

Print: 8,2 x 11,2 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 8,2 x 11,2 inches

Print: 8,2 x 11,2 inches INV Nbr. SW1502011 Kindly.

Print: 7,5 x 11,3 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,5 x 11,3 inches INV Nbr. SW1502015 Kindly.

Print: 7,5 x 11,3 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,5 x 11,3 inches INV Nbr. SW1502010 Kindly.

Print: 7,9 x 11,6 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,9 x 11,6 inches INV Nbr. SW1502006 Kindly.

Print: 8,9 x 11,4 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 8,9 x 11,4 inches INV Nbr. SW1502008 Kindly.

Print: 8,2 x 11,8 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 8,2 x 11,8 inches INV Nbr. SW1502014 Kindly.

Print: 8,7 x 11,2 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 8,7 x 11,2 inches INV Nbr. SW1502009 Kindly.

Print: 7,9 x 11,6 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,9 x 11,6 inches INV Nbr. SW1502002 Kindly.

Print: 7,5 x 11,4 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,5 x 11,4 inches INV Nbr. SW1502001 Kindly.

Image: 9 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artist

Image: 9 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. SW1502024 Kindly.

Print: 7,6 x 11,3 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,6 x 11,3 inches INV Nbr. SW1502019 Kindly.

Print: 7,3 x 11,4 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,3 x 11,4 inches INV Nbr. SW1502005 Kindly.

Print: 9,4 x 11,8 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 9,4 x 11,8 inches INV Nbr. SW1502021 Kindly.

Print: 7,5 x 11,6 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,5 x 11,6 inches INV Nbr. SW1502017 Kindly.

Print: 6,9 x 11,4 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 6,9 x 11,4 inches INV Nbr. SW1502016 Kindly.

Print: 7,5 x 11,3 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,5 x 11,3 inches INV Nbr. SW1502022 Kindly.

Print: 7,3 x 11,4 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,3 x 11,4 inches INV Nbr. SW1502018 Kindly.

Print: 7,5 x 11,1 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,5 x 11,1 inches INV Nbr. SW1502003 Kindly.

Print: 7,4 x 11,3 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 7,4 x 11,3 inches INV Nbr. SW1502023 Kindly.

Print: 8,9 x 11,4 inches

Signed by the artist

Print: 8,9 x 11,4 inches INV Nbr. SW1502007 Kindly.

Image: 9 x 5,4 inches

Print: 8,8 x 7 inches

Artist stamp and notes on verso

Image: 9 x 5,4 inches

Print: 8,8 x 7 inches INV Nbr. RM1502002 Kindly.

Image: 9 x 6 inches

Print: 8 x 10 inches

Signed, numbered and annotated in pencil by the artist and RKM Archive stamp on verso

Image: 9 x 6 inches

Print: 8 x 10 inches INV Nbr. RM1502001 Kindly.

Image: 8,9 x 6,1 inches

Print: 9 x 6 inches mounted on board 11 x 14 inches

Signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,9 x 6,1 inches

Print: 9 x 6 inches mounted on board 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. RM1502003 Kindly.

Image: 8 x 12 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on verso by the artist

Image: 8 x 12 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. AG1512011 Kindly.

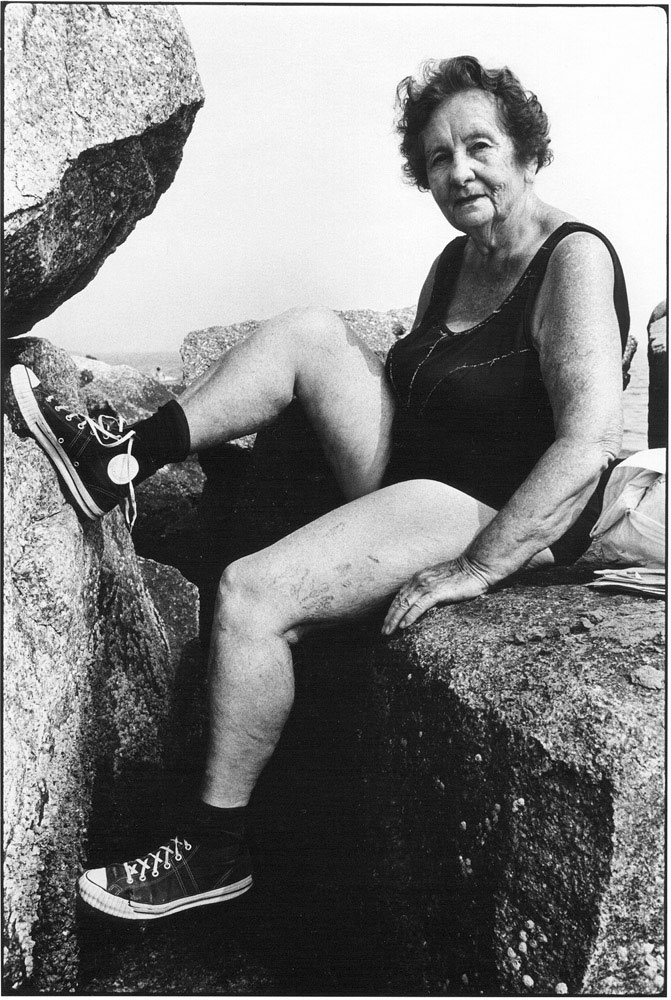

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on verso

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. AG1512010 Kindly.

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on verso by the artist

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. AG1512032 Kindly.

Image: 11,7 x 17,5 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 11,7 x 17,5 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. TA1406097 Kindly.

Image: 11,8 x 17,4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 11,8 x 17,4 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. TA1406092 Kindly.

Image: 8,3 x 12,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,3 x 12,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. TA1406039 Kindly.

Image: 13 x 10 1/2 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, maine on verso

Image: 13 x 10 1/2 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. BA1406006 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil on recto and stamped Abbot, Maine on verso

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. BA1406007 Kindly.

Image: 63,5 x 81,2 Inches

Print: 96,5 x 121,9 Inches

Image: 63,5 x 81,2 Inches

Print: 96,5 x 121,9 Inches INV Nbr. BA1609011 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 18 X 24 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 18 X 24 inches INV Nbr. EH1502003 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 2à x 26 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Frame: 2à x 26 inches INV Nbr. EH1502001 Kindly.

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on verso by the artist

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. AG1512016 Kindly.

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on verso by the artist

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. AG1512026 Kindly.

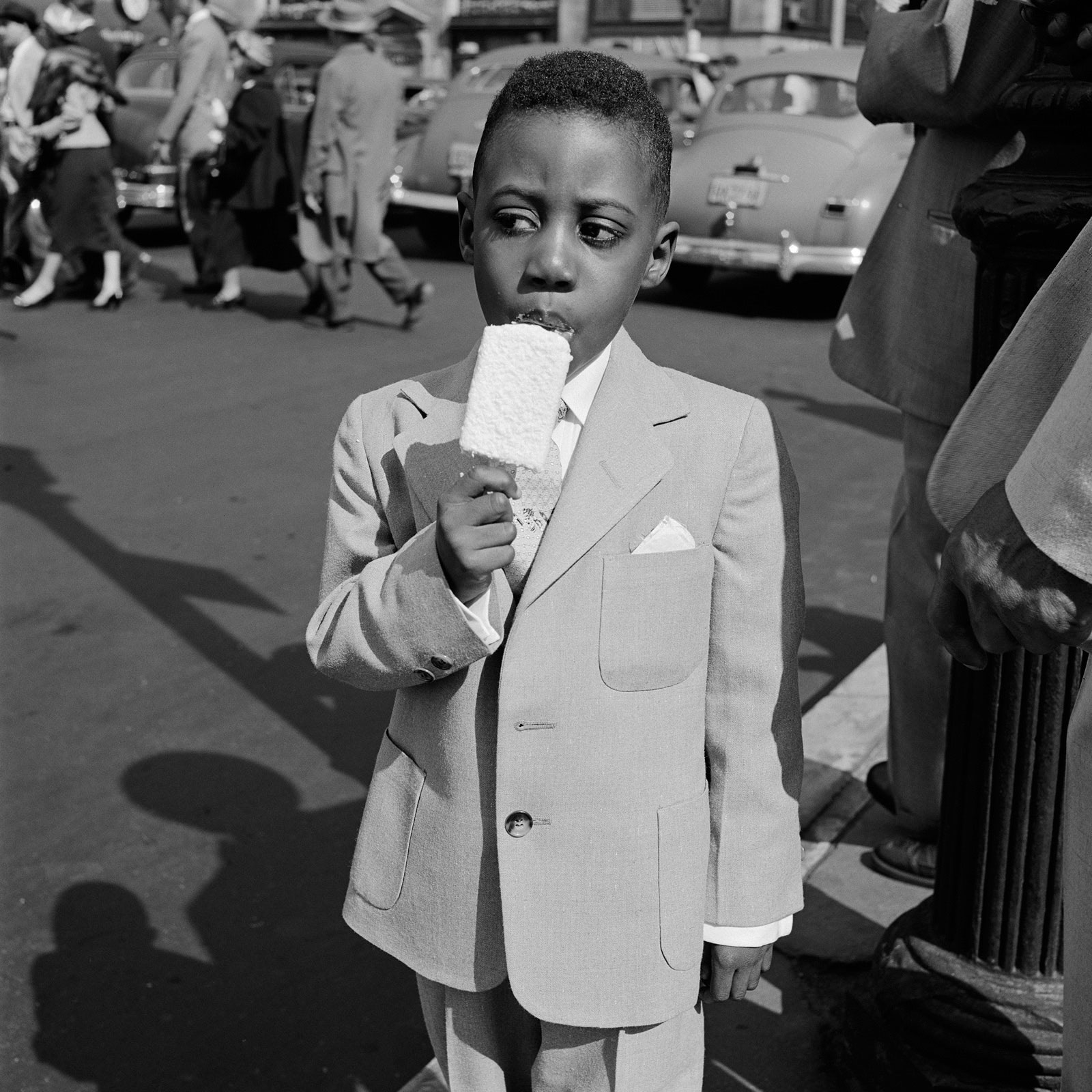

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. VM1501007 Kindly.

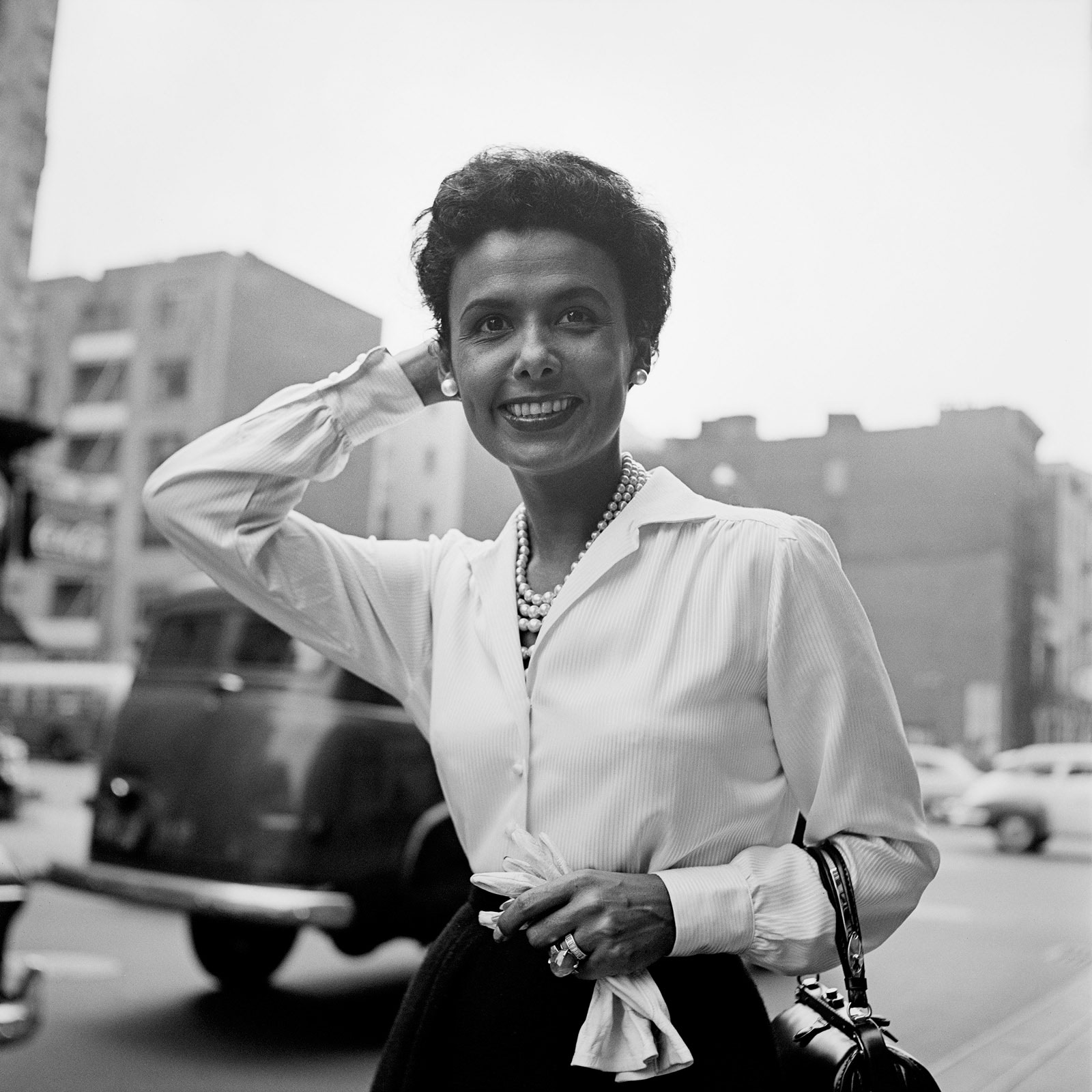

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. VM1401009 Kindly.

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. VM1501006 Kindly.

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed and stamped by John Maloof

Image: 12 x 12 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. VM1501003 Kindly.

Image: 12,5 x 8,5 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed by the artiste

Image: 12,5 x 8,5 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. HL1503005 Kindly.

Image: 9,5 x 14,125 inches

Print: 14,25 x 17,75 inches

Signed by the artiste

Image: 9,5 x 14,125 inches

Print: 14,25 x 17,75 inches INV Nbr. HL1503001 Kindly.

Image: 6,375 x 9,5 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed by the artiste

Image: 6,375 x 9,5 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. HL1503004 Kindly.

Image: 12,25 x 8,375 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed by the artiste

Image: 12,25 x 8,375 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. HL1503002 Kindly.

Image: 9,5 x 14,125 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed by the artiste

Image: 9,5 x 14,125 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. HL1503003 Kindly.

Signed by the artist

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on verso by the artist

Image: 6 x 9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches INV Nbr. AG1512029 Kindly.

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Print authenticated by Alex Haas, moral right holder

Print: 16 x 20 inches INV Nbr. EH1502002 Kindly.

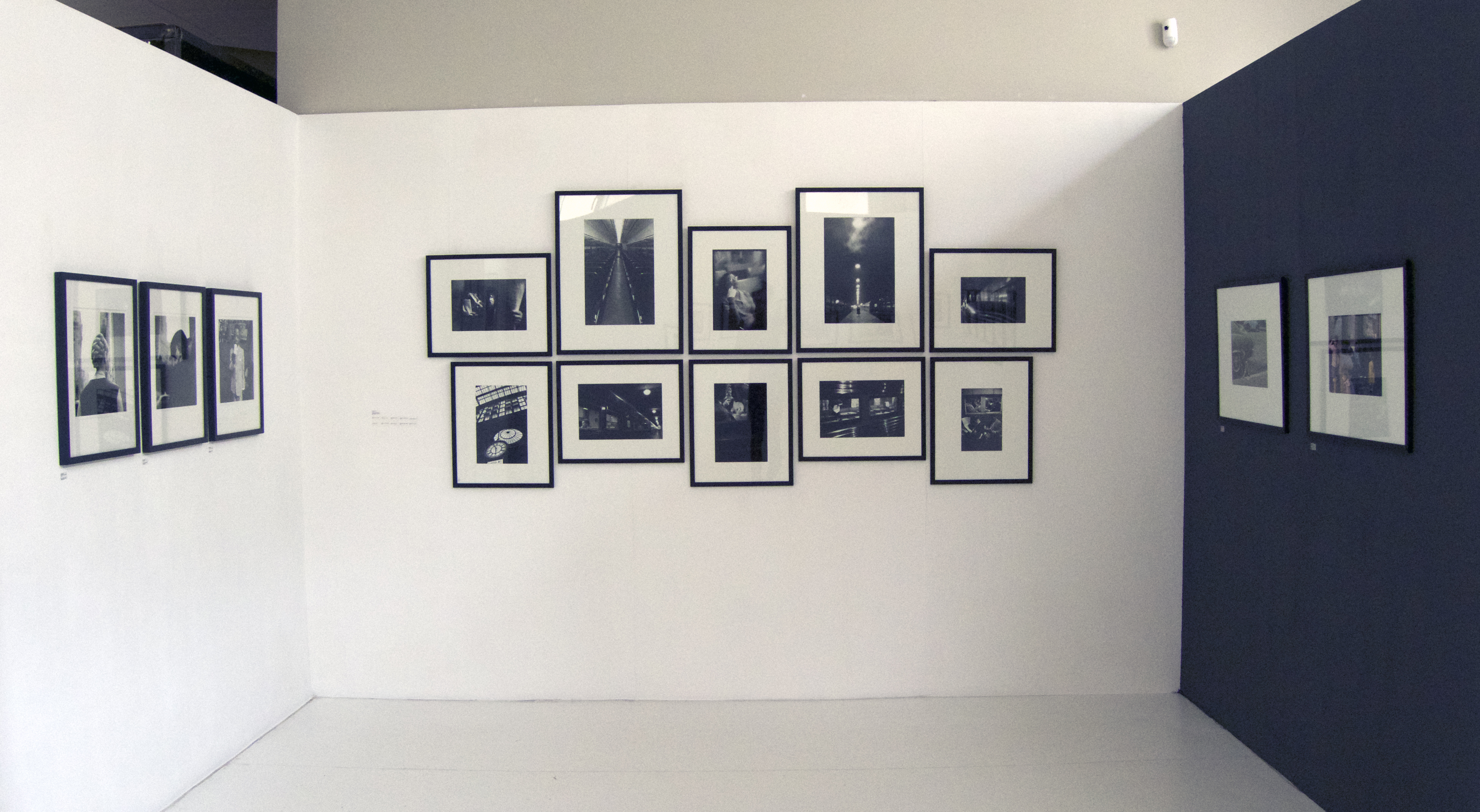

Presentation

We are pleased to announce New York, a group show including Berenice Abbott, Tom Arndt, Arlene Gottfried, Ernst Haas, Helen Levitt, Vivian Maier, Ray Metzker, Louis Stettner, and Sabine Weiss. Through a wide bench of photographs, the exhibition captures the spirit of this most fascinating city, each image possessing its own style. Whether they were born there, grew up there or even just regularly came to visit, each of the artists exhibited has a personal look, focusing on architecture, people, or on the hectic life of New York City.

Press

PRESS RELEASE

“There are roughly three New Yorks. There is, first, the New York of the man or woman who was born there, who takes the city for granted and accepts its size and its turbulence as natural and inevitable. Second, there is the New York of the commuter – the city that is devoured by locusts each day and spat out each night. Third, there is the New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something.”

E.B. White, Here is New York, 1949.

New York was arguably the most photogenic city of the 20th century, or at least the city that most inspired this new art form. Photography was born and blossomed here, firstly in a purely artistic form using the modern city as its subject, just as a landscape might be celebrated by painters. It is the place where Alfred Stieglitz’s pictorialism originated, in a time before the easel tradition had become anchored in academicism or as part of the new impressionism, fauvism or cubism. Documentary photography however (whose evolution we can observe here in its infancy with Berenice Abbott or in its contemporary forms with Arlene Gottfried) came about against an altogether different backdrop.

New York, a city of immigrants and tensions between ethnic communities (Black, Jewish, Italian, Puerto Rican, Hispanic, White Protestant, Tamil…) scattered throughout the various neighborhoods of its five boroughs, has inspired its young people, often happier in the streets than at school, to learn the trade of photographer armed with just a simple Kodak box camera, capturing on film images from their own neighborhoods and from passers-by of various origins, all looking so different. They were often themselves the children of immigrants, who were born or grew up in one of these boroughs: Helen Levitt, Louis Stettner and Arlene Gottfried in Brooklyn, Weegee, born Arthur Fellig in one of the Jewish areas and Vivian Maier, the most European of all, in the Bronx.

In the context of the Great Depression and the poverty that New York experienced between 1930 and 1940, some of its young amateur photographers became politicized and joined the Photo League, a group who organized the New York photography scene, involving exhibitions, publications, a school and genuine documentary projects about the city in crisis, its streets and many neighborhoods such as Midtown Tunnel Queens, Pitt Street, Lower East Side, Chelsea, Park Avenue and especially Harlem which had become a black ghetto. Such itineraries around the city were thus created and followed up by several generations of photographers including the ones presented here. Four of them (Berenice Abbott, Helen Levitt, Weegee and Louis Stettner) belonged to this group for some time before going their own way to pursue more personal projects. Berenice Abbott stands out because of her artistic and cultural background (she met Eugene Atget in Paris and taught photography) and her project to create an architectural inventory of an ever-changing New York.

With the newfound prosperity of 1941, the recognition of photography as a profession, the huge market of illustrated magazines and great museums embracing this new art form, New York photographers and foreigners who had come to New York gave a personal touch to their portraits of the city. Many photographers were involved, such was the appeal of a city which, since the early 20th century, had become iconic for the audacity of its architecture and the intense public life of its streets swarming with various communities resulting from incessant immigration.

It was first and foremost the architecture of a both immutable and ever-changing New York that inspired the photographers to make landmark pictures of iconic sights:

Penn Station

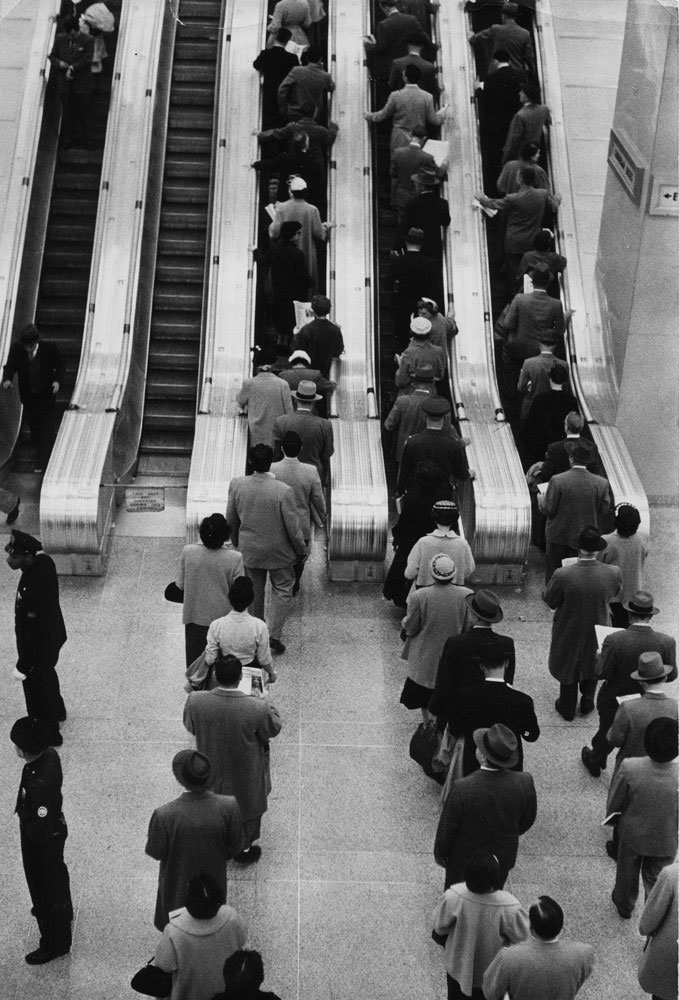

Every morning, hundreds of thousands of commuters would arrive at one of New York’s main train stations. For a long time, their eyes would be drawn to the massive clock at the center of the dark hall under the extensive glass ceiling of Penn Station, the glorious structure built in 1903, modeled after the Roman Baths of Caracalla and shamelessly torn down in 1963. Were Louis Stettner and Sabine Weiss aware of the fact that they were capturing – following in the footsteps of Berenice Abbott in 1930 and shortly before its demolition – this travelers’ interchange and its clock, whose refined Roman numerals emerged against the chiaroscuro of the stained-glass skylight? Berenice Abbott wanted to capture the railway track leading to Penn Station from the commuters’ starting point, on the other side of Hudson River: « I had had this spot in my mind for a long time. I’d often study a location for some while before I’d take a photograph. This was Hoboken and the skyline was purposely up the way it was. I wanted to show transportation coming into the city and later I took the other side - the yards of Penn Station - but the photograph was not nearly as good ».

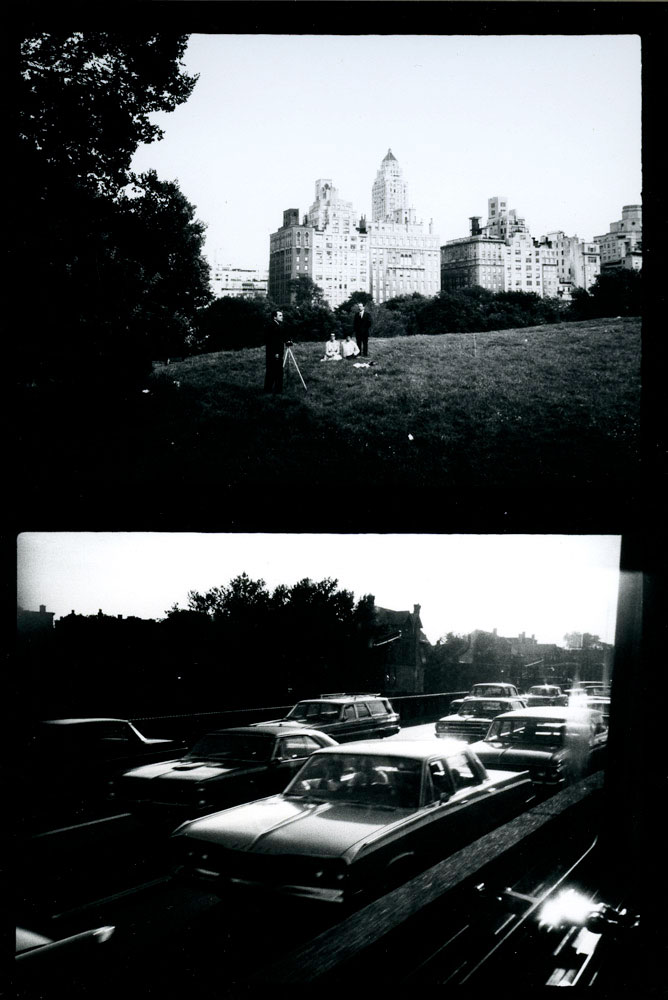

Louis Stettner, who was familiar with depicting factory workers, was also drawn to Penn Station and the diversity of these commuters:“the commuter is the queerest bird of all… works in New York, discovers nothing much about the city except the time of arrival of trains and buses, and the path to a quick lunch” (E.B White, Here is New York, 1949). All of them are frozen and keeping themselves busy on the train before the race through the city starts. The driver of a massive, abstract locomotive is focusing on getting them safe and sound to their destination. Empty carriages or departing trains are captured in the semi-darkness of underground tracks located six meters underneath the big hall and lit by large stained-glass windows.

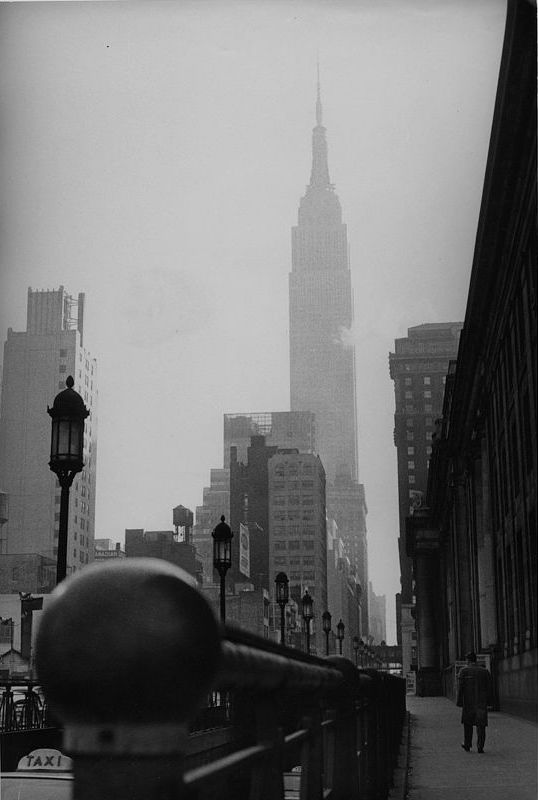

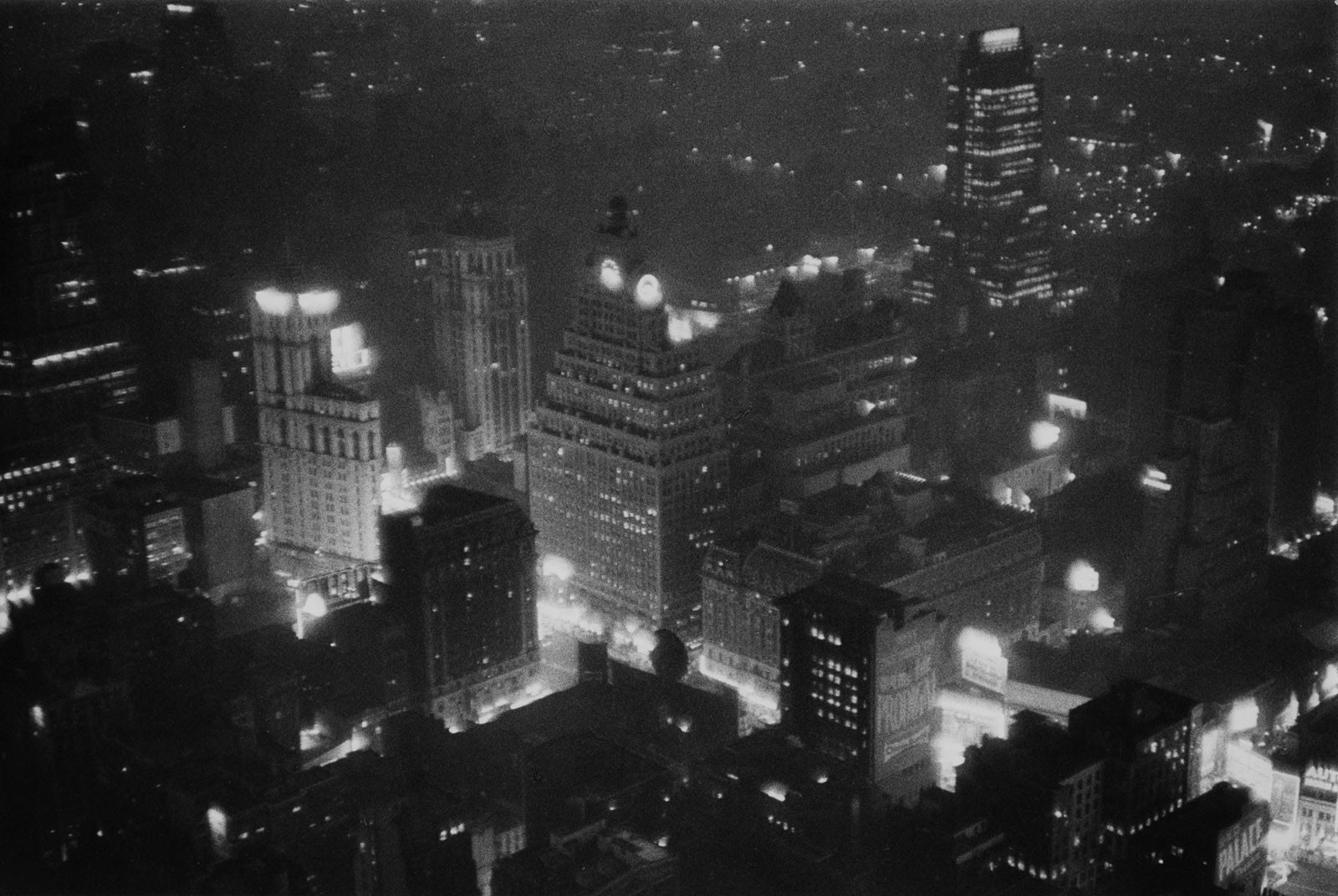

The Empire State Building

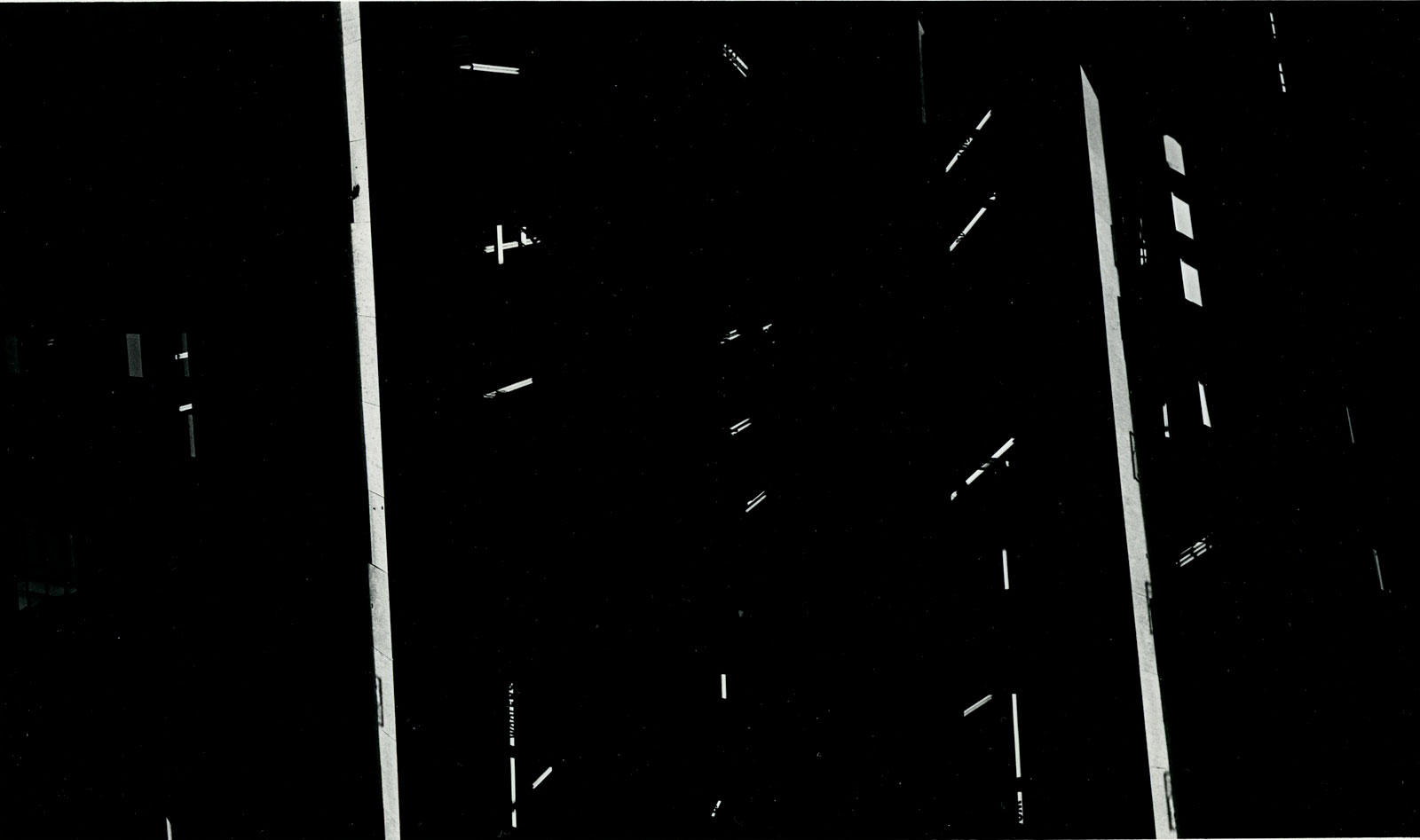

The iconic skyscraper built in 1931 on Fifth Avenue and Midtown was for a long time the roof of the urban world, offering the largest viewpoint of Manhattan. Photographers took possession of this watchtower, as have tourists of yesteryear and today alike. Lewis Hine was the pioneer as he was hoisted up to the 100th floor in a kind of basket on November 25th, 1930, in order to document men working at height. All photographers mentioned here must have remembered Lewis Hine for this feat as well as his work on the city’s slums. Berenice Abbott crept up the building at nightfall in order to capture Manhattan lit by offices at the end of a working day: “I had done a good deal of prior planning of the photograph, going so far as to devise a special soft developer for the negative. This was a fifteen-minute exposure… I was at a window, not the top of the building… They always thought you wanted to commit suicide…” She placed her large camera, a Century Universal 8x10, and took the picture. Sabine Weiss created her own picture of the Empire State Building by finding a perspective from a taxi rank on a side street, hence emphasizing the massive silhouette of the skyscraper and the verticality of New York. But she also went up one of the skyscrapers to capture Manhattan by night – creating an impression of flying over the city, which is technically forbidden.

The Flatiron Building

Another site had already featured in the imagery of photographers, the Flatiron Building, whose audacity as the first skyscraper had made it very controversial upon its construction in 1902 and which Alfred Stieglitz captured first hand in the bleak light of a rainy day – which suited his taste for blurring. After him came Edward Steichen, and the list was to become longer. It took Berenice Abbott two attempts: “… this is the better version; there is no doubt in my mind that this building looks better from the street level and I was careful in picking the precise location to set my camera.”

Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Bridge

You won’t see New York’s ultimate icon, the Brooklyn Bridge. Instead, the young black guy who is sat on a bench in Brooklyn Heights, the favorite promenade for lovers in the city, beholds Manhattan and the bridge for you. Louis Stettner disclosed this view through the eyes of a local guy or a visitor to Brooklyn, the place for New York’s ethnic and cultural vibrancy where three of our photographers were born: Louis Stettner himself, Helen Levitt and Arlene Gottfried.

In 1930, a young photographer, Walker Evans, armed with a simple single-lens bellows camera, captured the gigantic iron and stone silhouette of the black deck of the Brooklyn Bridge across the East River, hence participating in the emergence of modern cityscape photography.

Crowds in the streets, the rise of street photography in New York

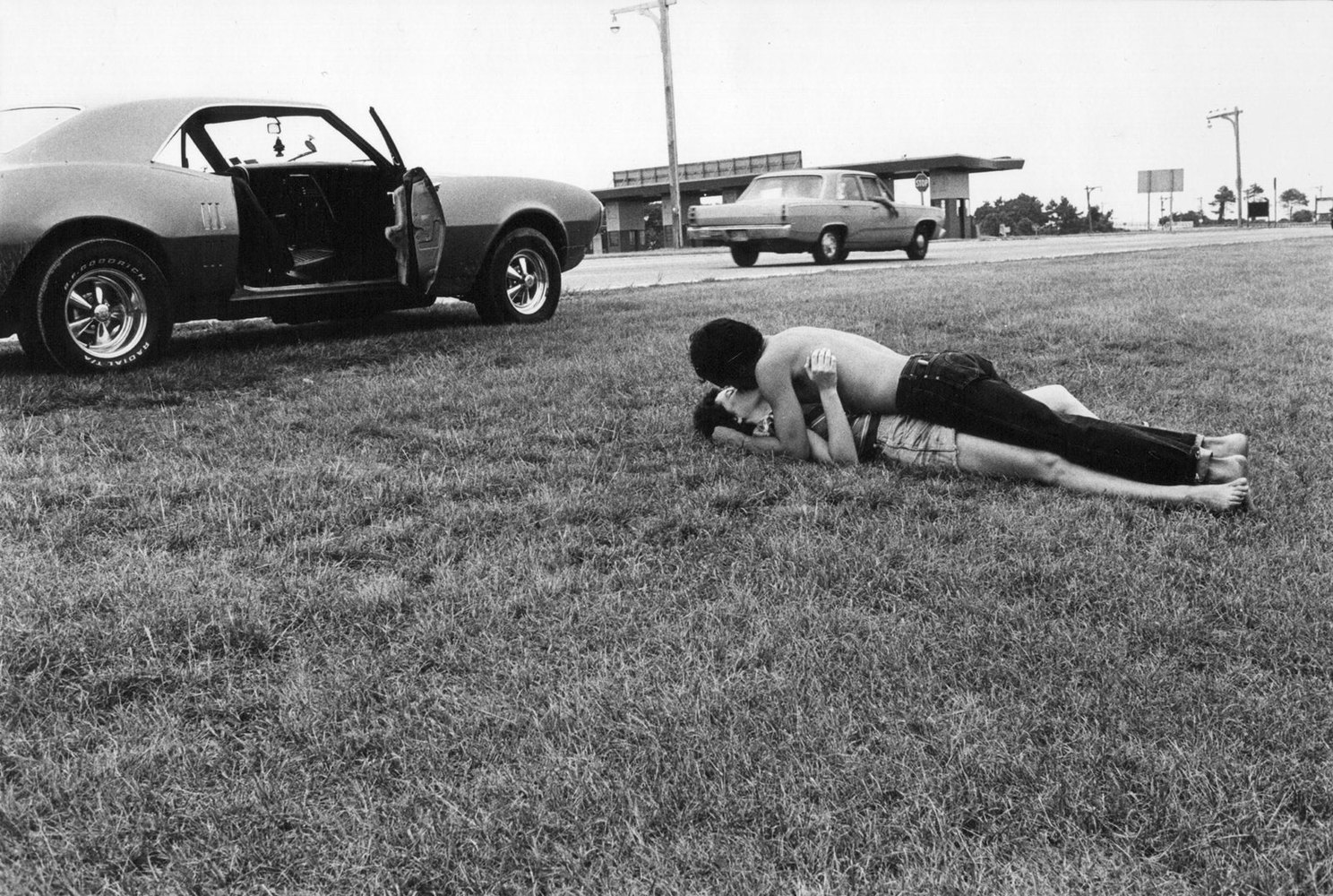

In spite of the change from prosperity between the 1940s and 1960s to the financial and social crisis of the 1970s and 1980s, and the vanishing of the old ordnance of streets and avenues “that filled up city blocks to near solidity” (New York 1960, collective), streets and neighborhoods are still swarming with life.

Capturing the street on film? : “It is any public place where a photographer could take pictures of subjects who were unknown to him and, whenever possible, unconscious of his presence.

“At the same time that street, as subject matter, is dealt with almost as if it had its own personality, imposing it self upon (or perhaps seducing) any photographer who confronts it. The sensibilities of the photographers themselves are also too varied for their individuality to be denied.”

(Colin Westerbeck & Joel Meyerowitz, Bystander, A History of Street Photography).

Each artist had their own project and their own perspective on the street: Helen Levitt, armed with a Leica ensuring swiftness and flexibility, would improvise: “I would go out and shoot, follow my eyes – what they noticed, I tried to capture with my camera, for others to see.” A great contribution from women!

Ethnologists, like photographers, have understood that a woman is better accepted than a man when observing other people’s natural behaviors. There is less suspicion, less holding back on one side, and seemingly more attention and interest for the individual’s uniqueness on the other. Such seemed to be the operation mode of Berenice Abbott, Helen Levitt, Vivian Maier, Sabine Weiss or Arlene Gottfried – whether from New York or not.

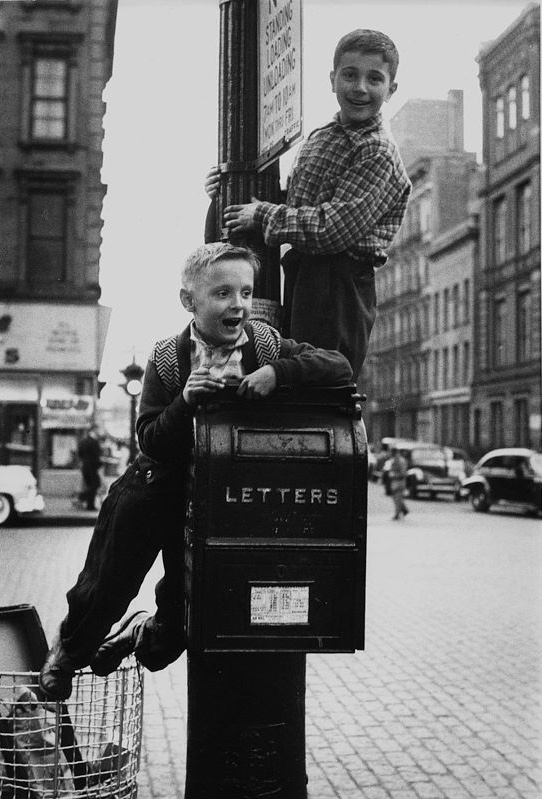

Children were the most welcoming subjects, even in neighborhoods with tensions between communities. The street is their own territory, they play in a place where other people would be running to work, away from the photographer. They are not afraid, they are not wondering why anyone would want to photograph them, they do not see it as intrusive or rude but may hope for a reward. Their families would be less keen, especially if you tried to get into their homes. No picture taken indoors here, which would have allowed Sabine Weiss to ask the subjects to strike the pose again, as she may have wished, in the style of Robert Doisneau. As a photographer of Parisian children too, she owned up to her cunning method: “Obviously I have a playful connection with children, I like to challenge them into doing something, laugh with them… You can’t do that with adults.”

Helen Levitt approached the world of children as a world of play (she was keen on chalk drawing) and laughter. It was a unique world, especially when the street belonged to everyone: “The neighborhoods are different. They’re not full of children anymore. In the 1930s there were plenty of kids playing on the street. The streets were crowded with all kinds of things going on, not just children. Everything was going on in the street in the summertime. They didn’t have air conditioning. Everybody was out on the stoops, sitting outside, on chairs.”

Both contributed to the pacifist and humanistic project Family of Man in the 1950s, in which children are omnipresent, in particular on a double-page spread of the best-selling exhibition book featuring images by both Helen Levitt and Sabine Weiss.

Chance encounters and the unclassifiable

Once again, Vivian Maier fascinates us with her portraits captured in the streets. The most striking feature is not the good will of that black kid in his Sunday best, probably after a church service, but the reassuring image he gives of his own community. The artist’s most remarkable feat was the shot of Lena Horne, who seems to surrender so gracefully to the camera! Was she unexpectedly posing as a film star? Born in Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, this dazzlingly beautiful upper-class half-cast film star would soon end up blacklisted and banned from performing because of her stand against racism. In another street, we see the back of a white woman, her hair sophisticatedly done, who may not have noticed the presence of the photographer.

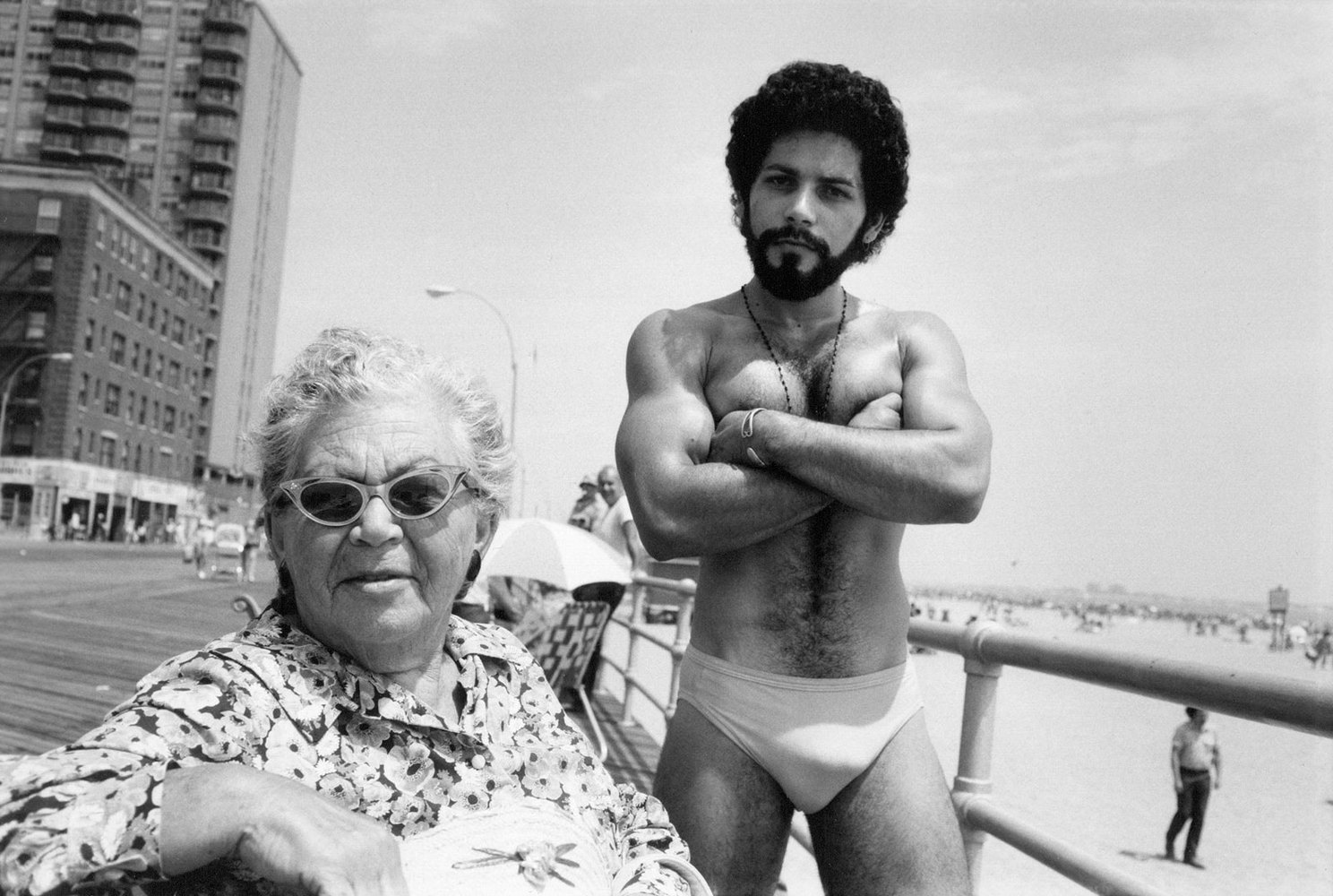

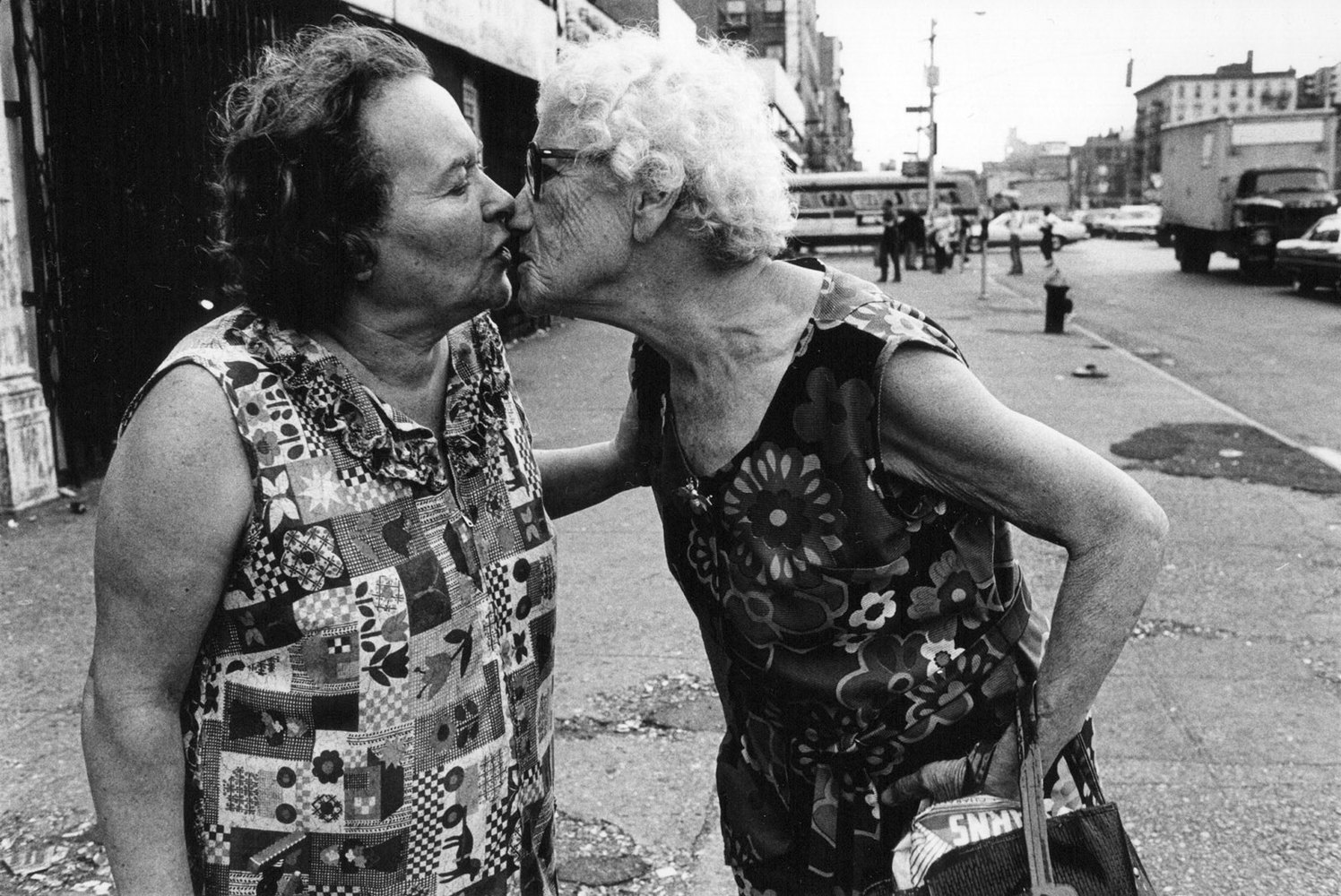

Arlene Gottfried made encounters of a different kind. She would relentlessly explore the city’s working-class areas, Lower East Side, Brooklyn, Queens, and photograph people she did not know, with special attention to those who had been pushed away by gentrification. She tried to show the uniqueness of ordinary people, especially older women, who are free from expected kinds of behavior or styles of clothing. They went out in the streets or on beaches brazenly, sometimes in unlikely company. We discover typical places of working-class entertainment, from Coney Island, a place very dear to Weegee, to the Russian quarter nearby with its bars and restaurants often visited by Tom Arndt.

Overwhelmed by the intensity of urban street life, Gottfried claimed to be “a quiet defender of the grimily vibrant denizens of an older New York that’s disappearing daily”.

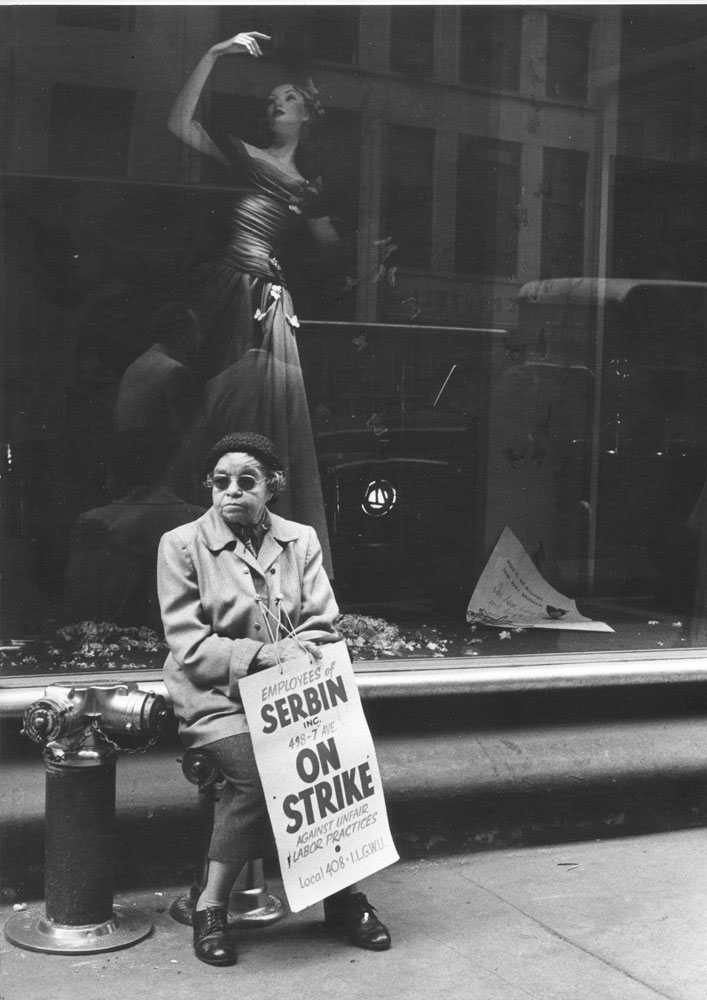

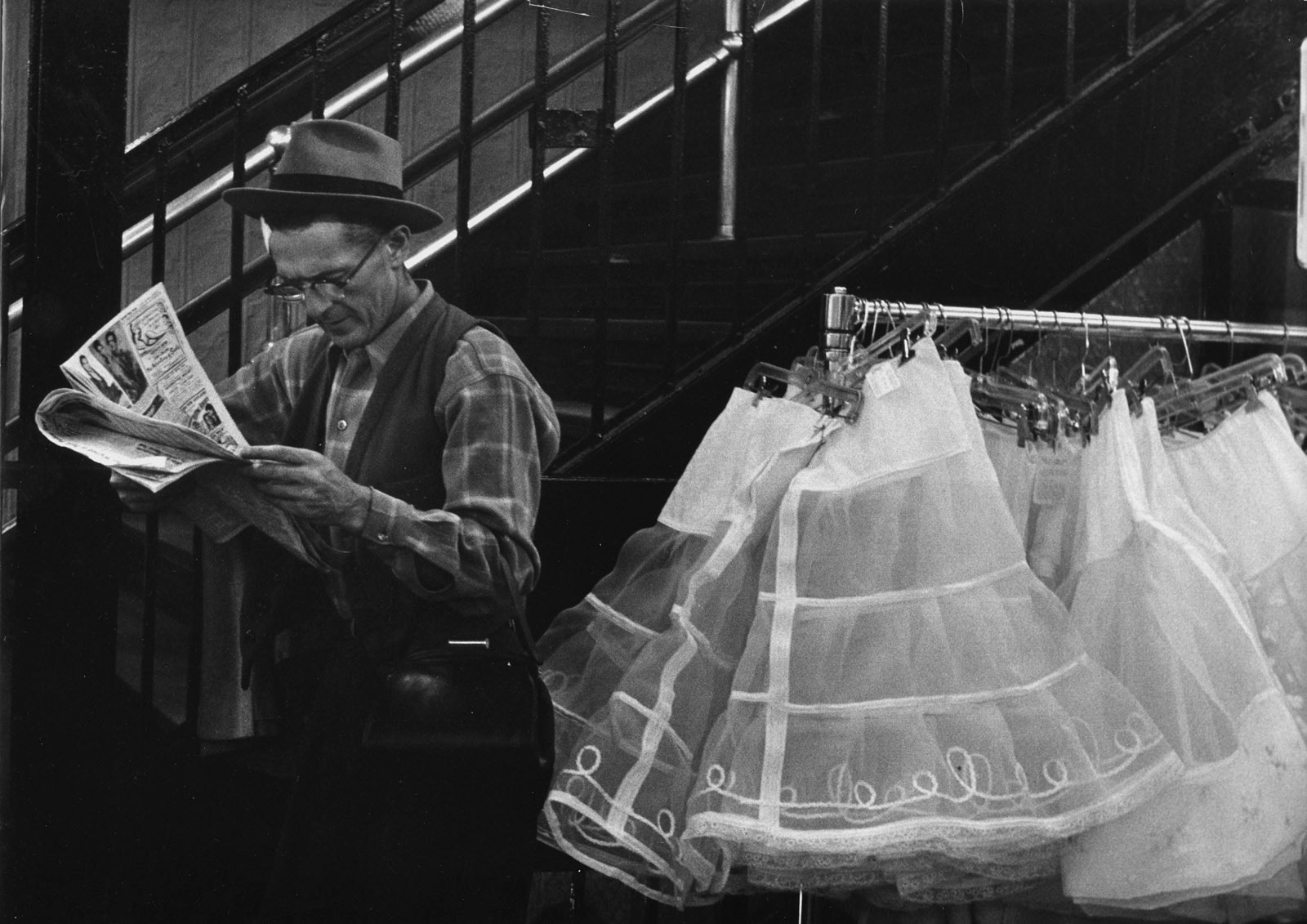

Small trades and garment making

Wandering around streets and neighborhoods, each with its own character, Sabine Weiss observed various small trades, and more specifically the second biggest industry after consumer staples – garment making. A black woman on strike in the Garment District (the Sentier of New York), looking impassive and determined, with a beautiful model wearing an evening dress in the background… Other garment workers carrying racks of white evening dresses around Manhattan… In Little Italy or Orchard Street, the former street of Jewish immigrants, the “bargain district” for children’s clothes… We can almost hear what’s being said.

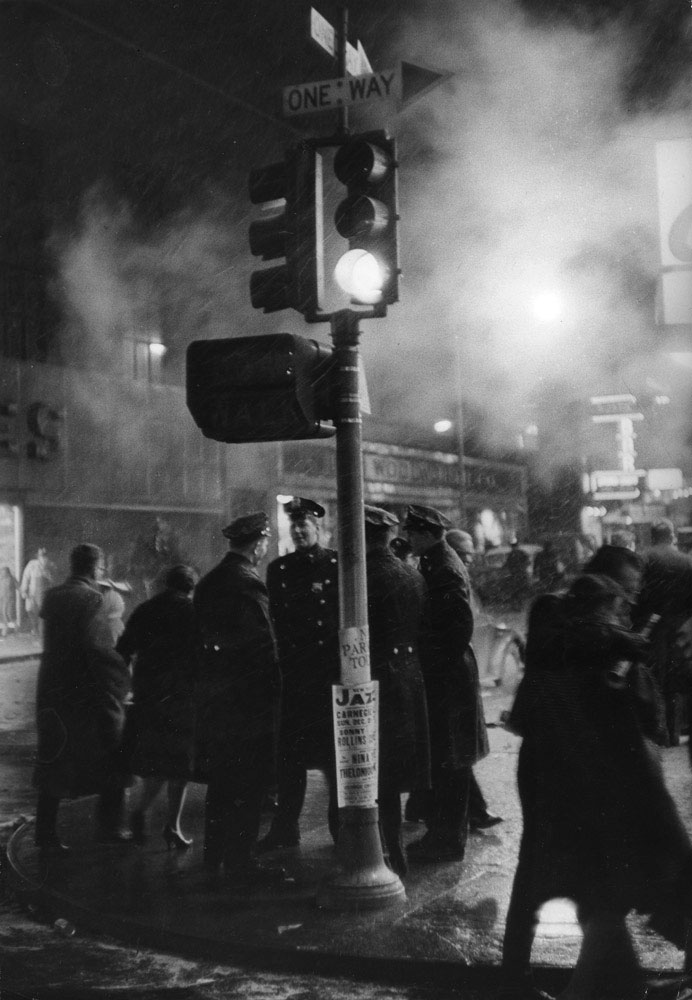

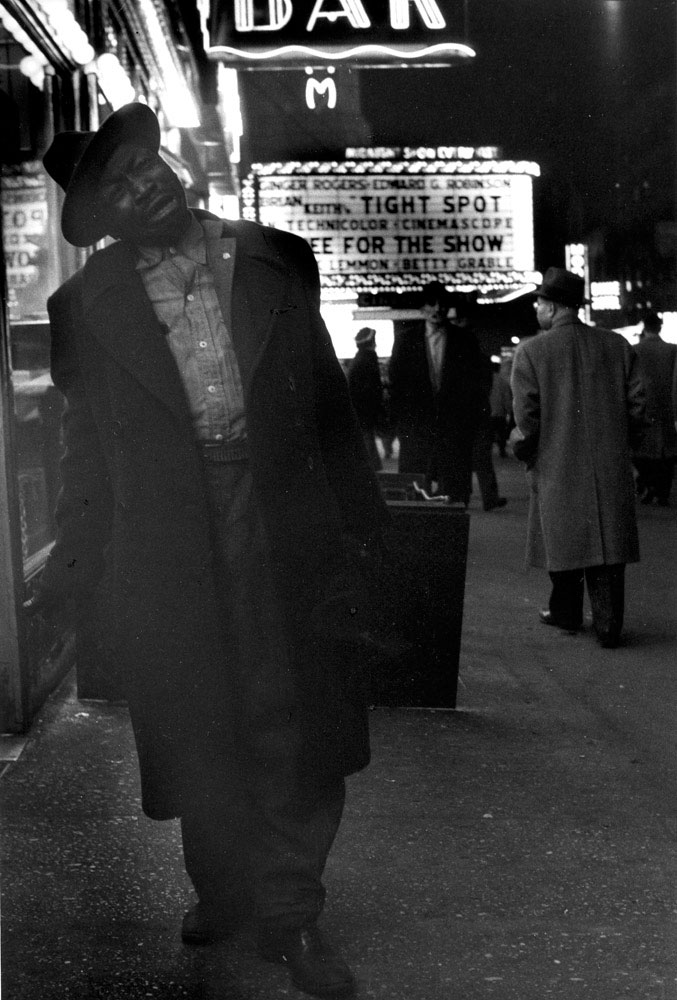

Nighttime

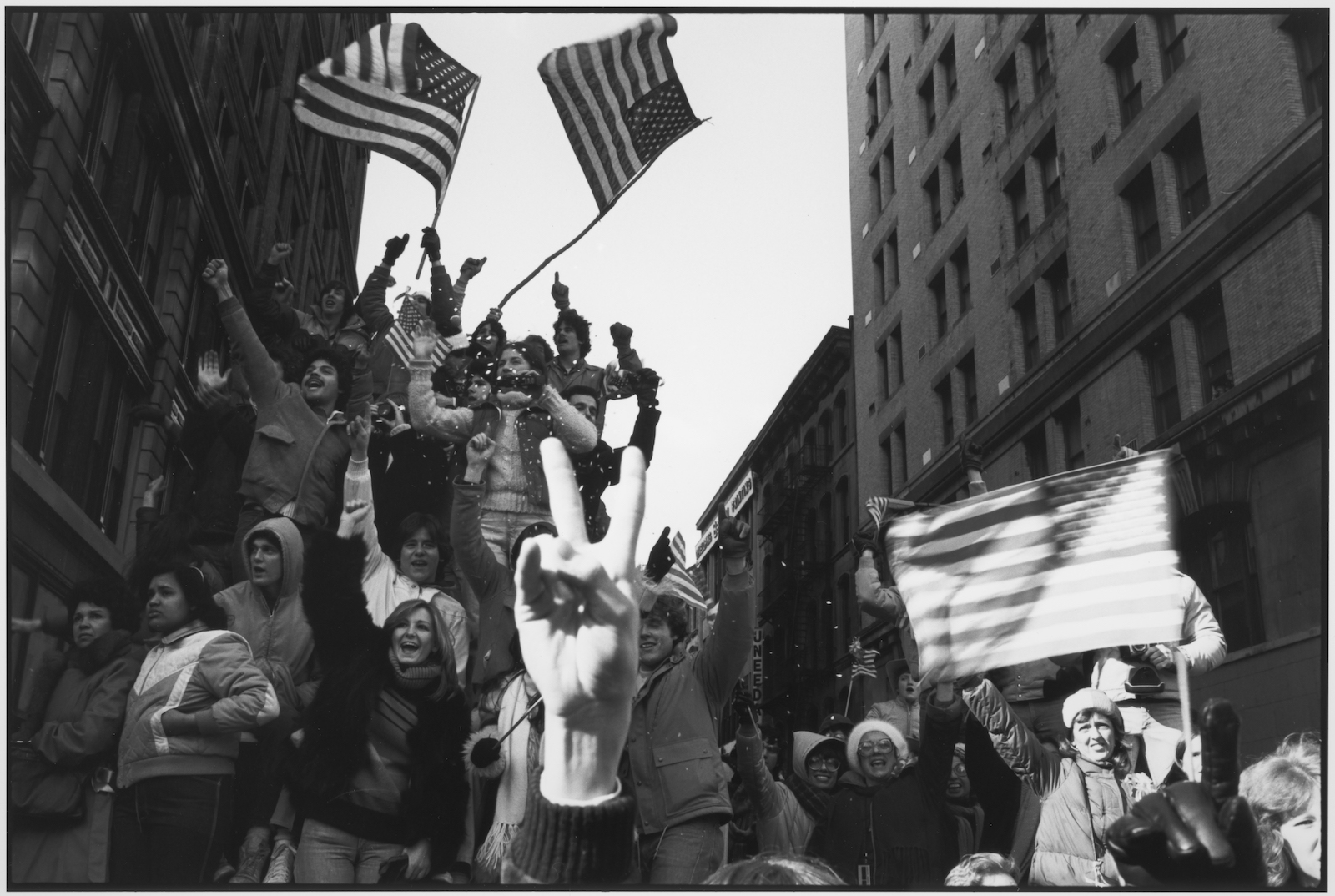

New York is awake 24 hours a day, as if shifts took over from each other to ensure that the night doesn’t disrupt life: “I stood the other night looking North from Forty Second Street into his narrowing cañon... The Broadway signs are our folk art writ in fire in the sky... When I turn into Broadway by night and am bathed in its Babylonic radiance, I want to shout with joy, it is so gay and beautiful. I melt into the river of pleasure-seekers.” (Broadway, Atlantic Review, June 1920) Sabine Weiss is indeed melting into the teeming crowds of Times Square, amongst the silhouettes of those who have come from all over the world and feel at home here “in the real New York”, as modern New York wanderer William Helmreich put it. Debonair policemen are watching, they are not yet on the job like those that Weegee would follow every night. Meanwhile, Tom Arndt was following other night workers, those who do “the dirty job”, cleaning up the mess left behind by July 4th (National Day) revelers.

A visual world of shapes

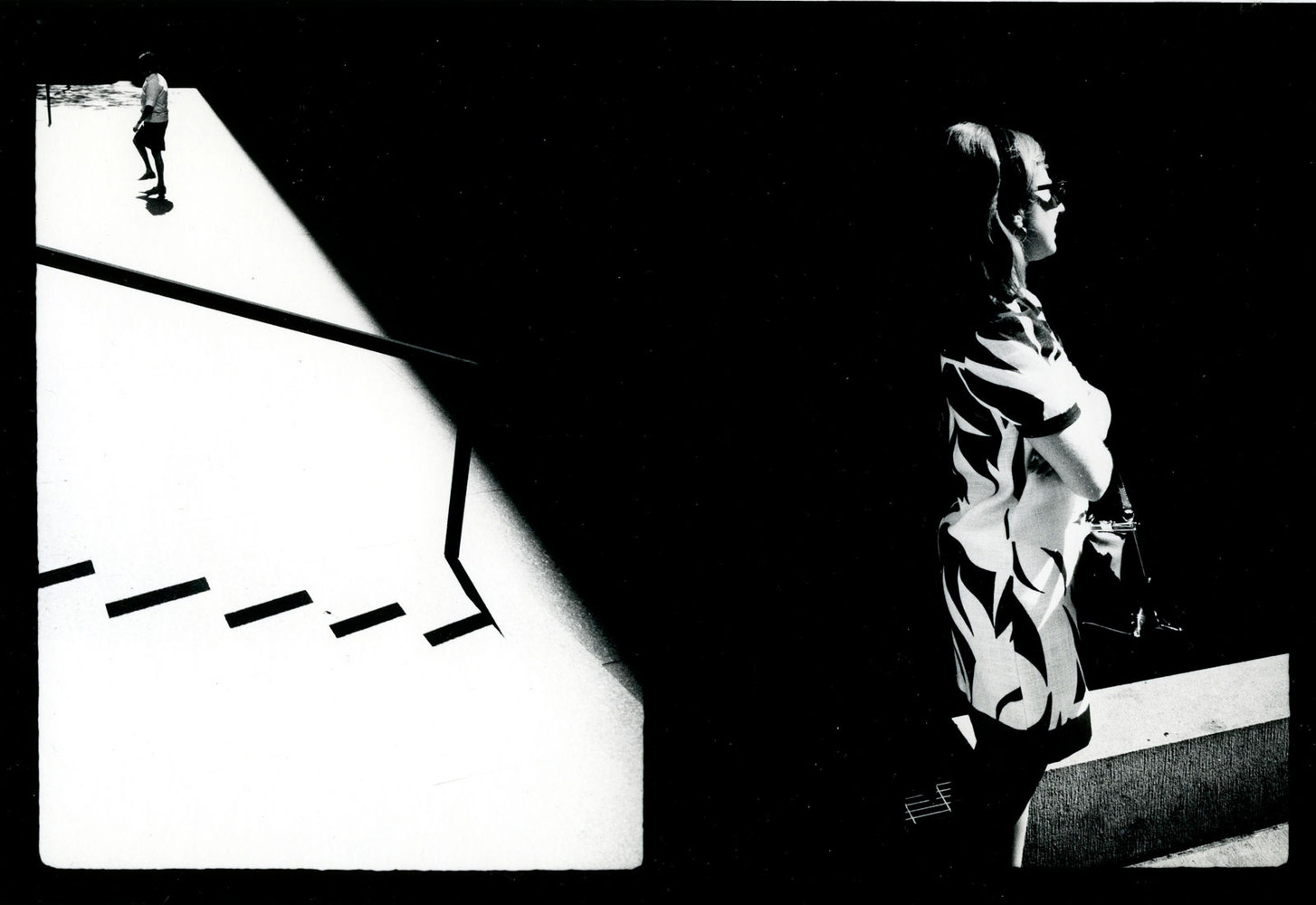

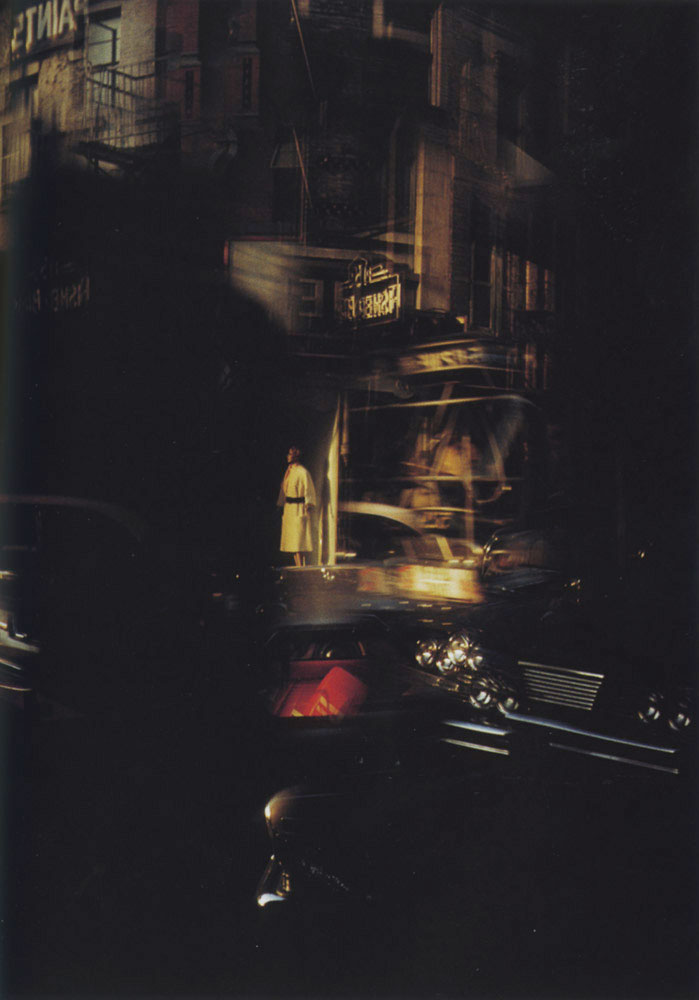

The street has ceased to be an obvious reality of shapes easily identified by the passer-by; it has become a construction of moving shapes. Ray K. Metzker, trained to rigorous artistic discipline at the Chicago Institute of Design (Bauhaus transferred to the United States), wanted to use his camera and the streets of New York – after Chicago – to explore “the visual possibilities of blur, focus, vantage point, framing and light” (Lloyd C. Engelbrecht, Taken by Design, Educating The Eye, 2002). A formal project rather than a documentary.

Another immigrant mesmerized by the beauty of New York, Ernst Haas opted for color: the street is no longer a mere public space for interactions between people but a geometry of shapes seen through a kaleidoscope: a car’s windshield, signs with basic graphics, another car emerging from the fumes of urban heating.

To conclude, let’s quote John Szarkowski, the famous curator who ruled the department of photography of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for over thirty years. In 1967, in the preface for his “New Documents” exhibition, he wrote:

“Most of those who were called documentary photographers a generation ago, when the label was new, made their pictures in the service of a social cause. It was their aim to show what was wrong with the world, and to persuade their fellows to take action and make it right.

“In the past decade a new generation of photographers has directed the documentary approach toward more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life, but to know it. Their work betrays a sympathy almost an affection for the imperfections and frailties of society. They like the real world, in spite of its terrors, as the source of all wonder and fascination and value no less precious for being irrational…”

Henri Peretz

Sociology professor at University Paris VIII

Historian of photography

Senior fellow Yale University