Tom Arndt

Image: 8,2 x 12,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Image: 8,3 x 12,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Image: 7,6 x 11,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Image: 8,1 x 12,2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Image: 8,6 x 12,7 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Image: 7 x 10,3 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 12,2 x 8,3 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,1 x 12,2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 14,5 x 14,5 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8 x 12 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,3 x 12,1 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 7,7 x 11,7inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,9 x 13,5 inches

Print: 14 x 17 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 11,4 x 16,9 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 9,4 x 9,5 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 12 x 17,7 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 11,4 x 15,2 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Image: 8,4 x 5,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Image: 12 x 18 inches

Print: 16 x 20 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 10 x 7 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 4 x 6 inches

Print: 8 x 10 inches

Signed, titled and dated on pencil by the artist

Image: 6,3 x 8,8 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 9,9 x 10,1 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 12 x 8 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,3 x 12,4 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,6 x 12,9 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 7,6 x 11,5 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 7,2 x 10,2 inches

Print: 11 x 14 inches

Titled, dated and signed by the artist on verso

Image: 8,9 x 13,5 inches

Print: 14 x 17 inches

Signed on pencil by the artist on verso

Presentation

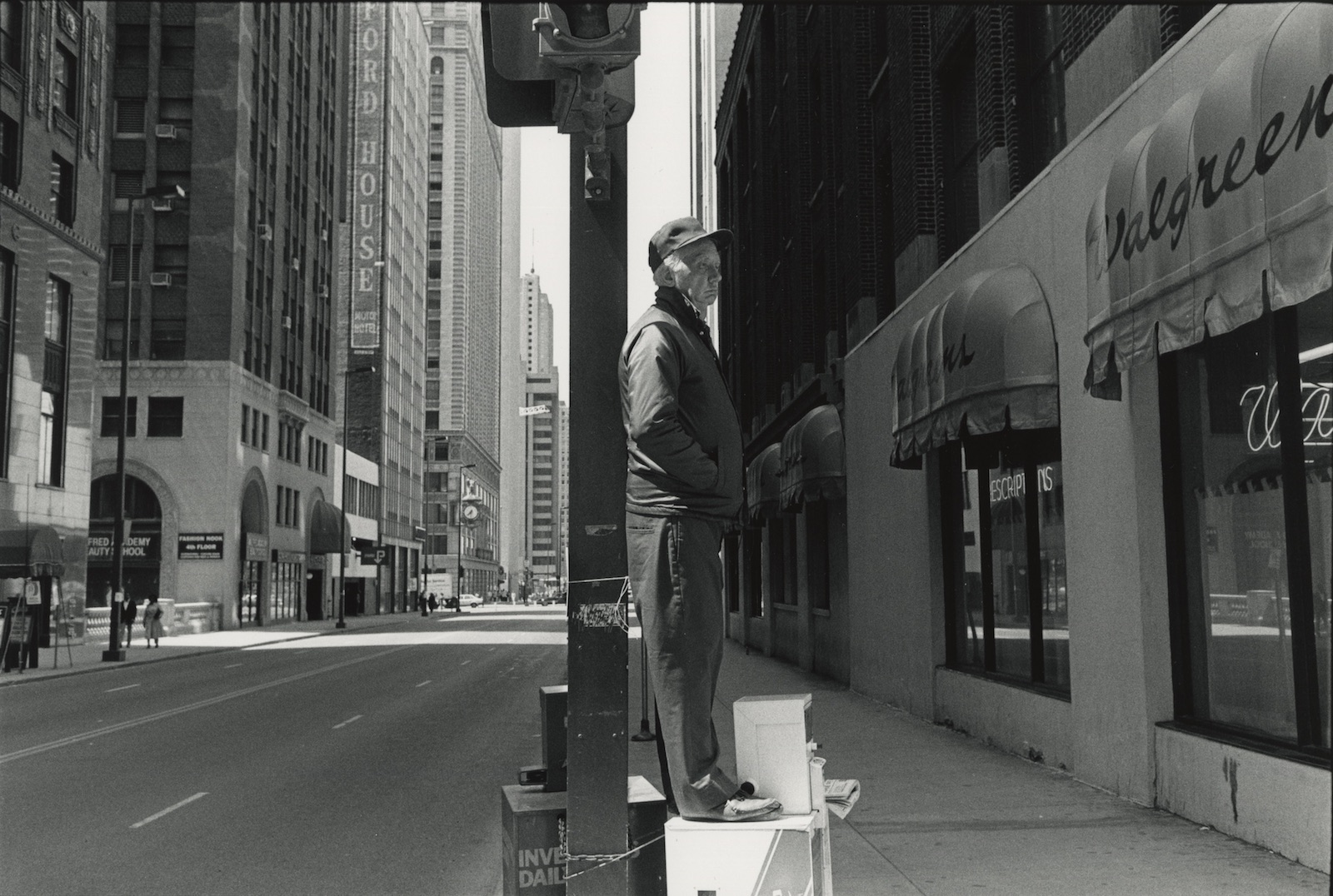

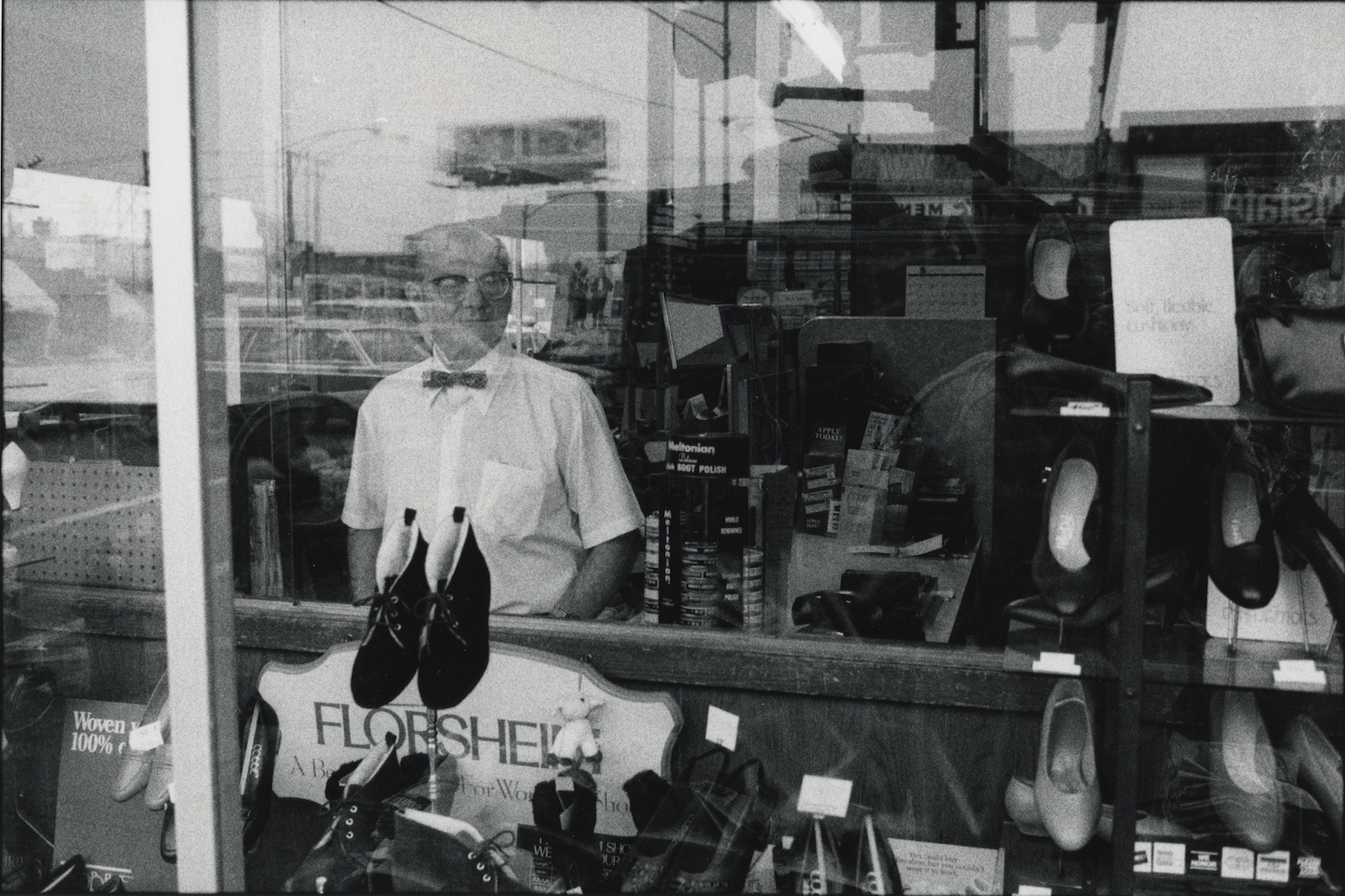

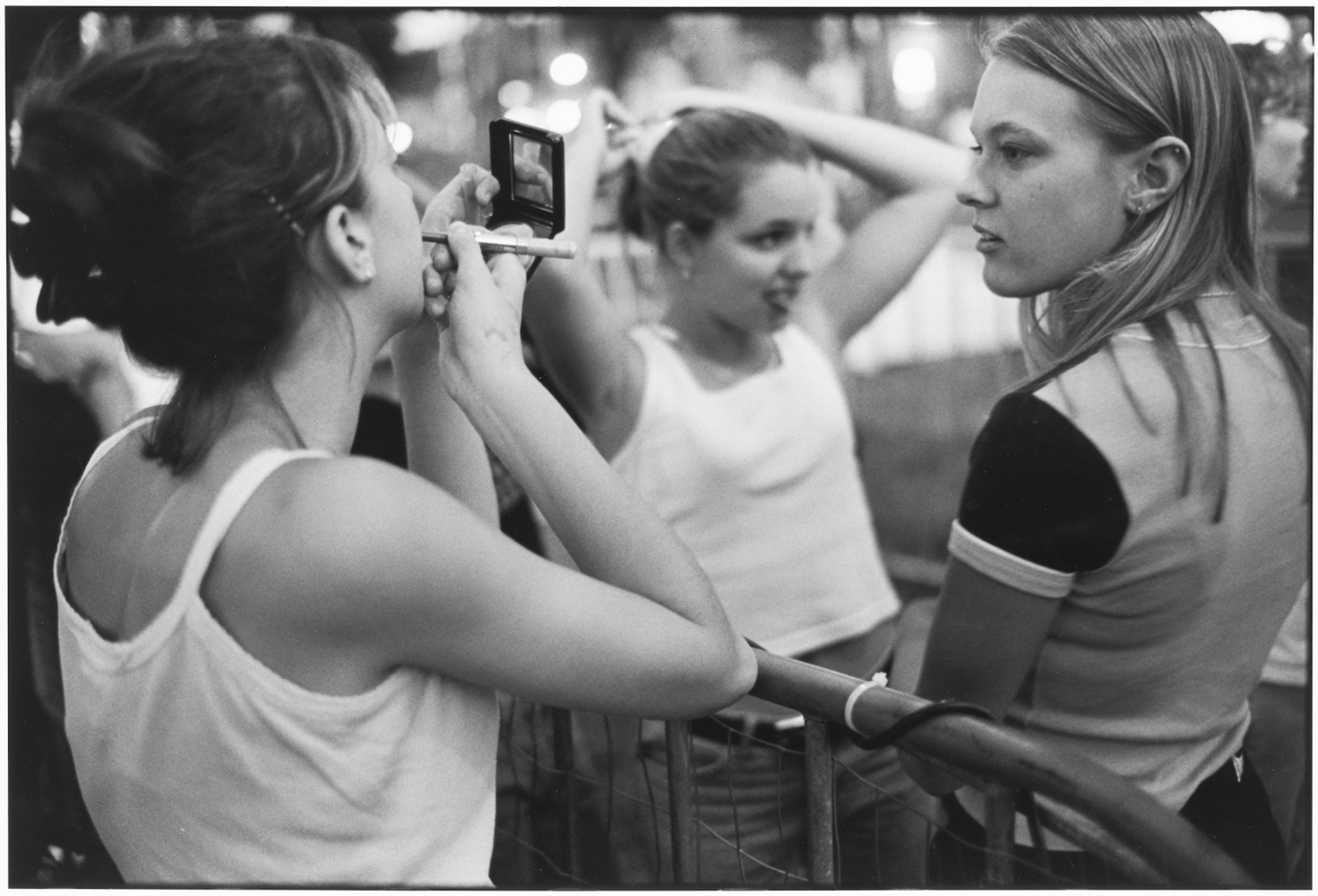

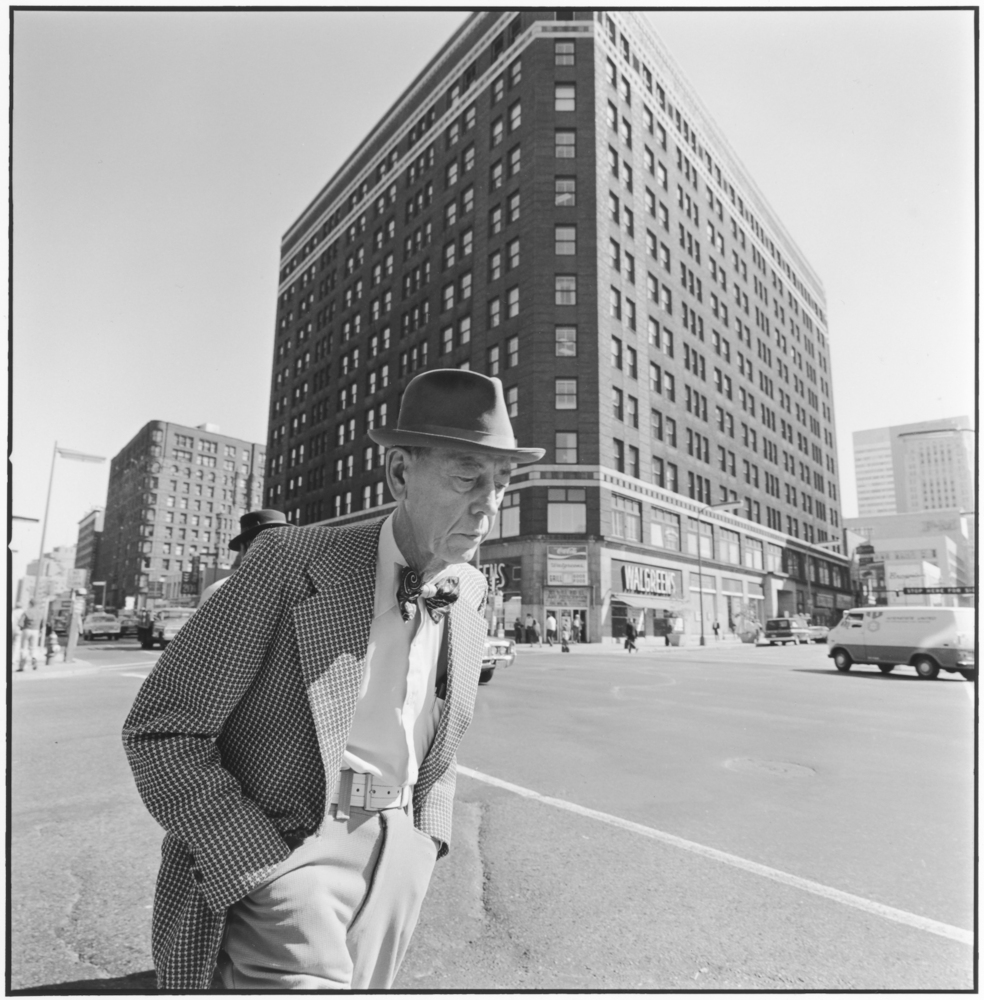

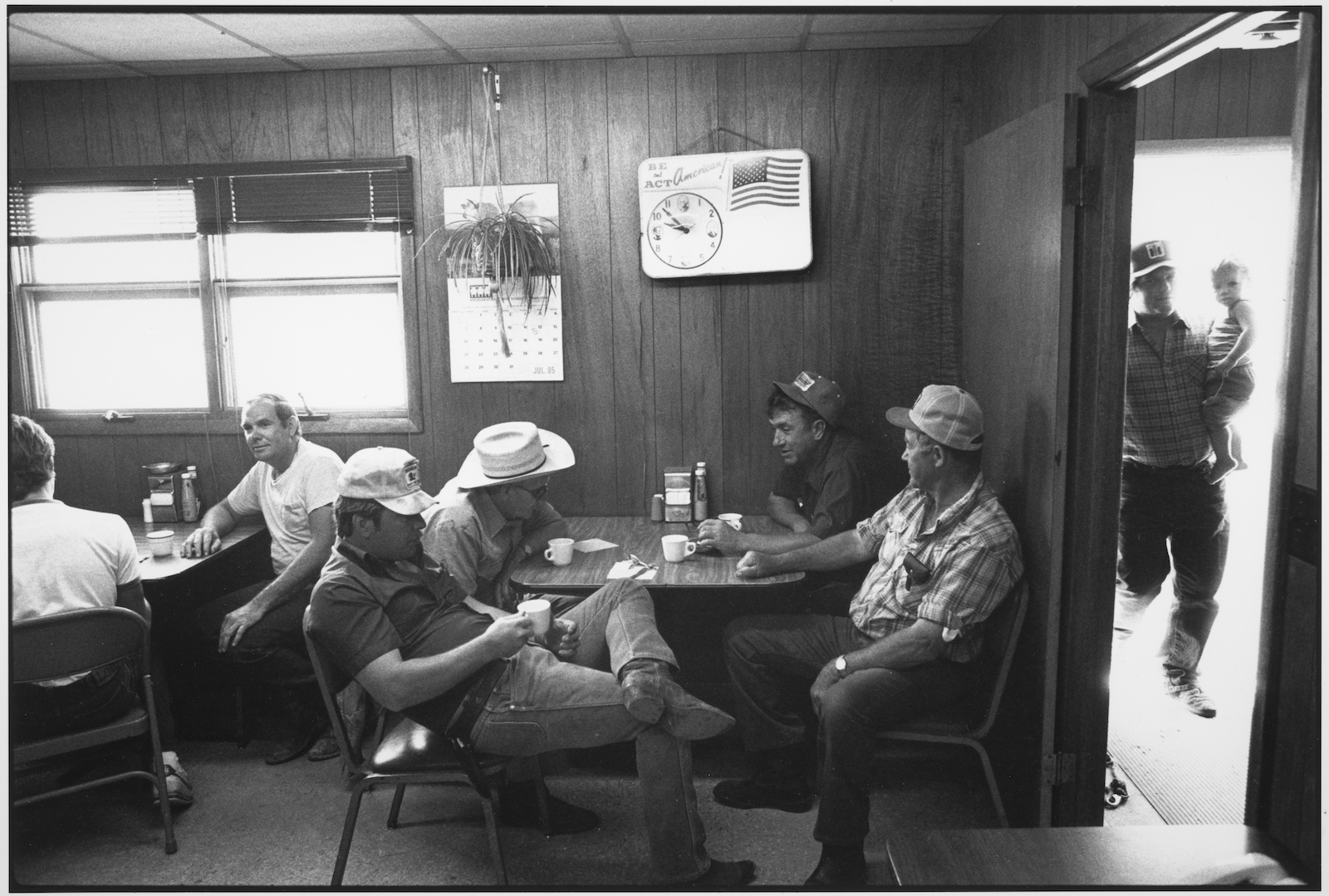

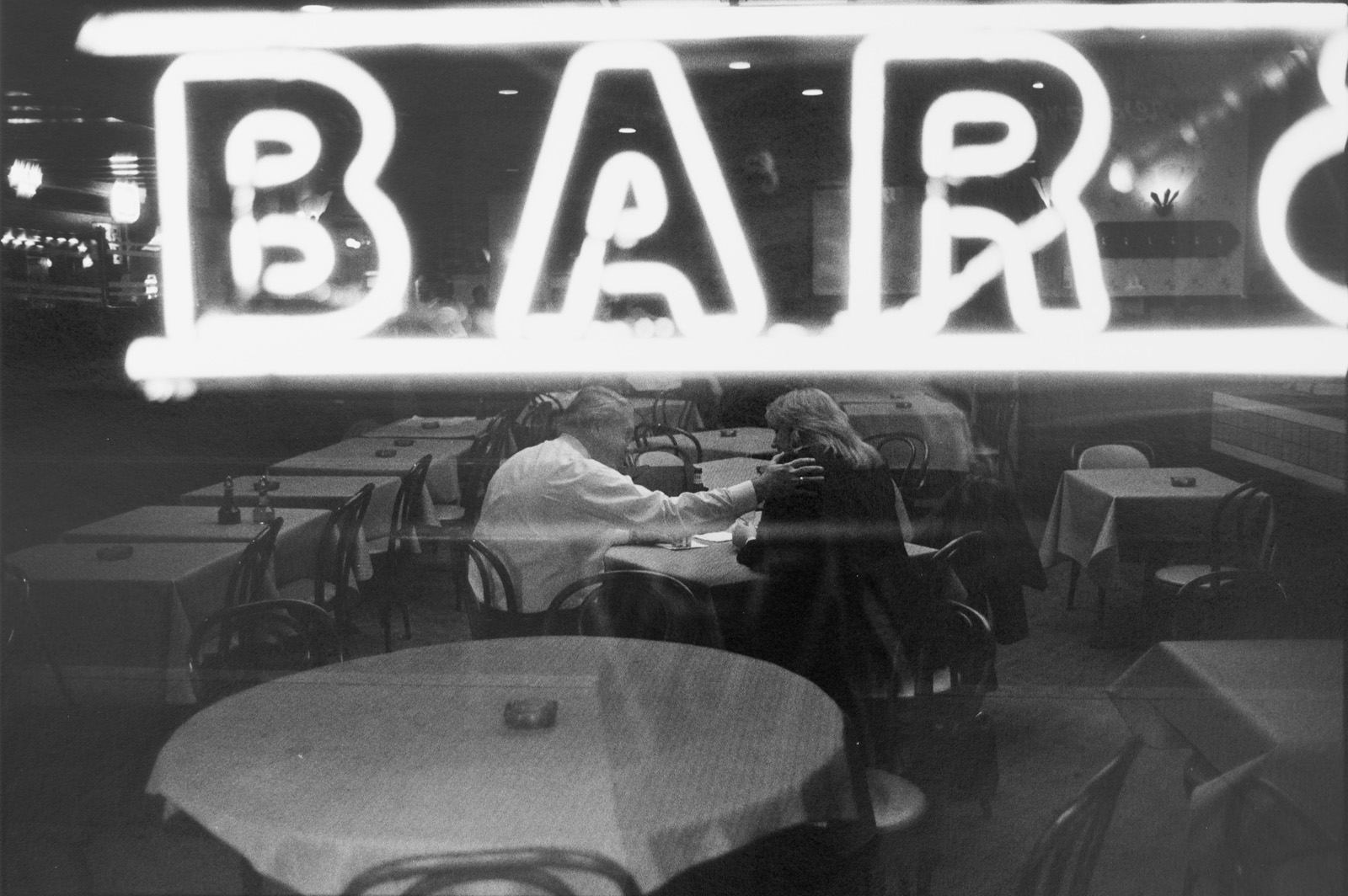

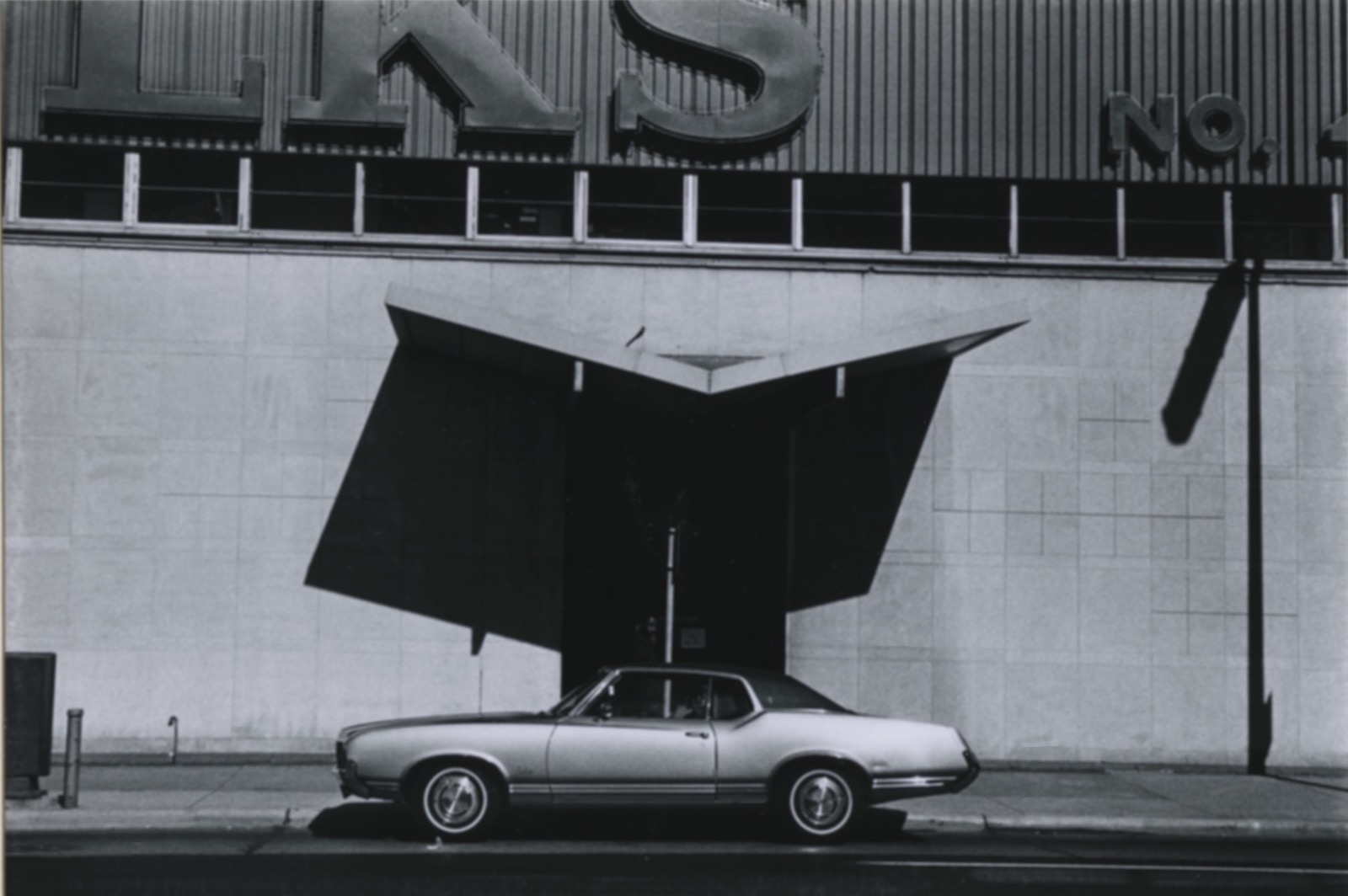

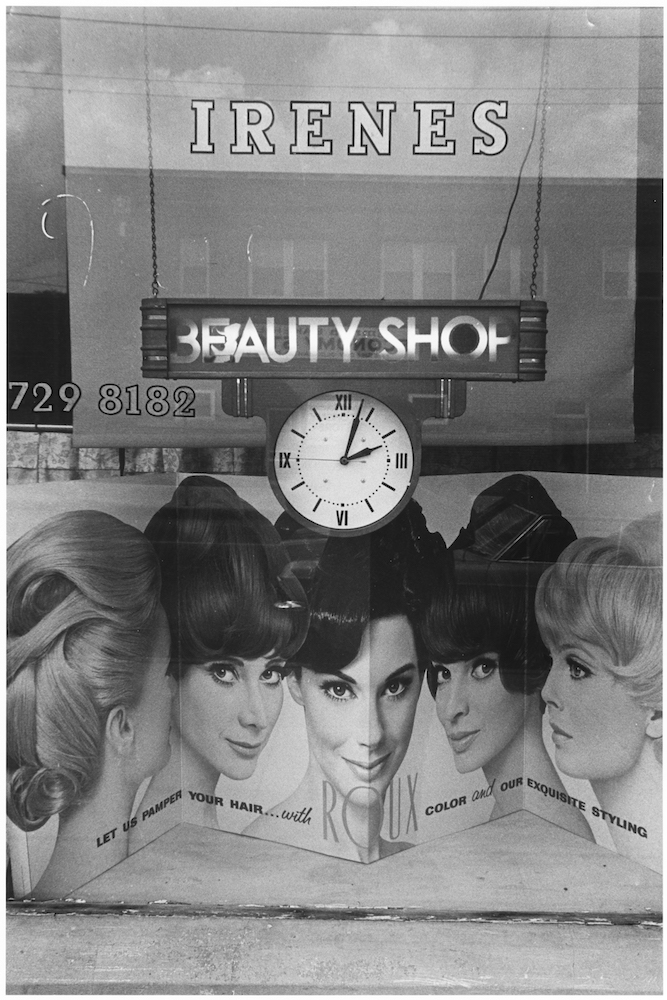

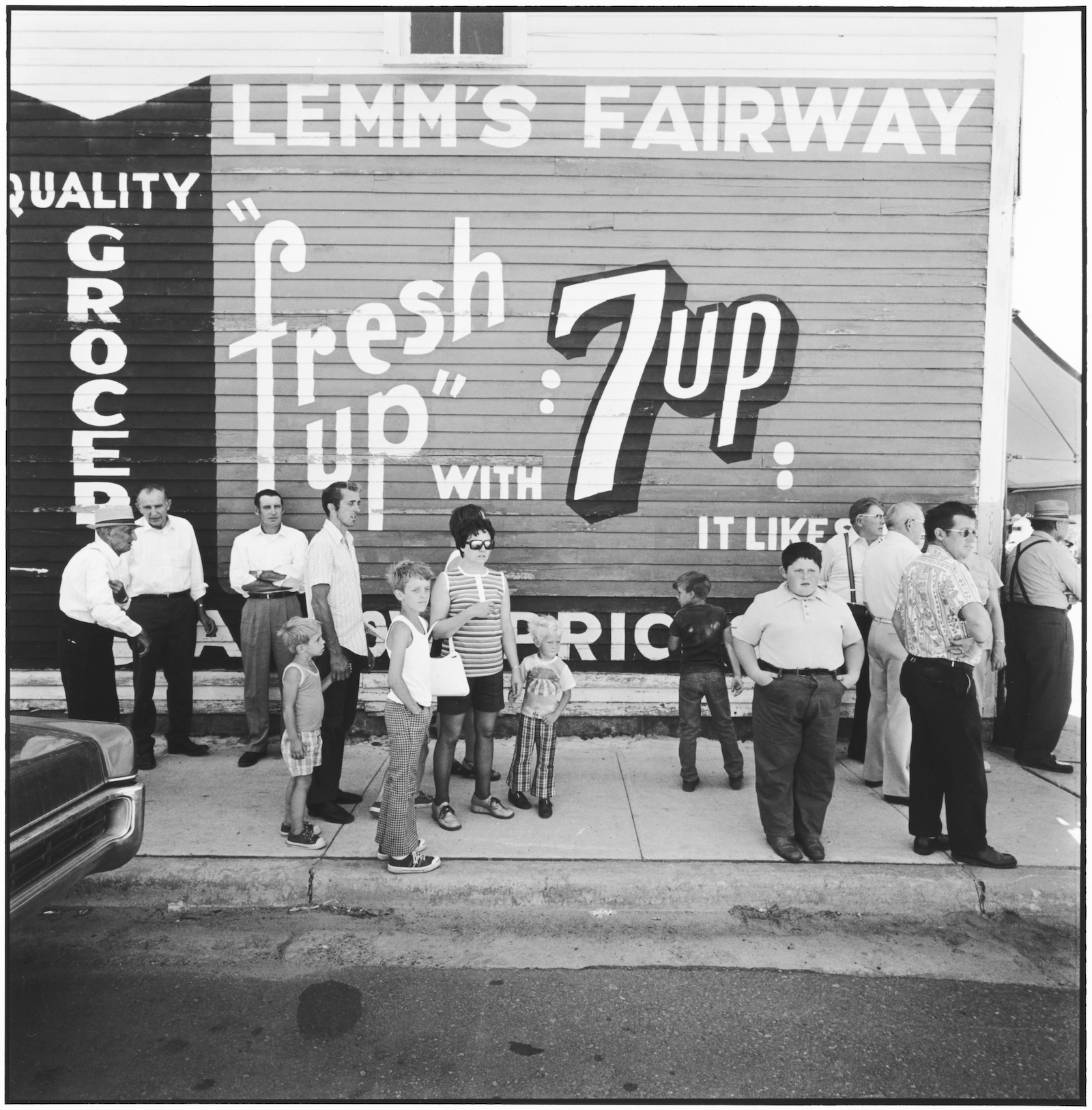

Born in Minneapolis, Tom Arndt's photography focuses on his native Minnesota. Belonging to the grand, classic tradition of American documentary photography, Tom Arndt's body of work offers us a sensitive, empathetic portrayal: a family album of the people who live in his state including their coffee shops and soda fountains, their streets, their shop windows, their parks, the popular state fairs. Pessimism and pity are out of place here. As Arndt's friend and well known writer Garrison Keillor points out, Tom Arndt photographs the DNA of Minnesotan culture: the poor and the left out.

Tom Arndt belongs to the silver print processing tradition; his printing is exceptionally beautiful. He spends at least several hours daily in the darkroom; he really loves the paper print.

Arndt received a BFA from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (1968) and did graduate study at the University of Minnesota (1969-1971). His photographs have been exhibited at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Minneapolis Institute of Art; Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and other venues. His work is held in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Modern Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; George Eastman House, Rochester, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Public collections

Selected permanent collections

Museum of Modern Art, New York ; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art ; Menil Collection, Houston Texas ; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago ; Art Institute of Chicago ; Minneapolis Institute of Art ; George Eastman House ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art ; Walker Art Center ; Hallmark Collection ; Houston Museum of Fine Art ; Margulies Collection, Miami ; General Mills Collection

Press

Texts

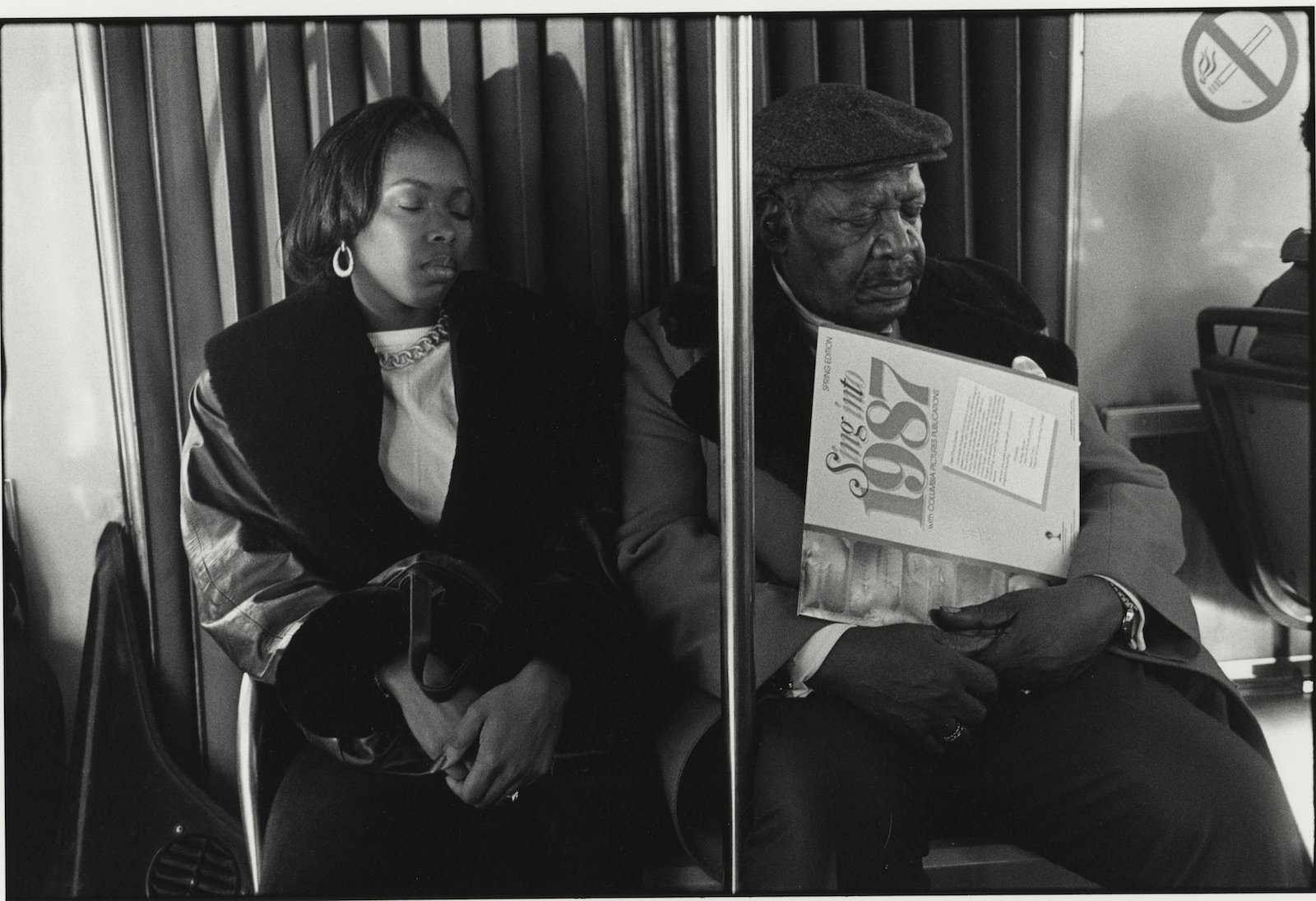

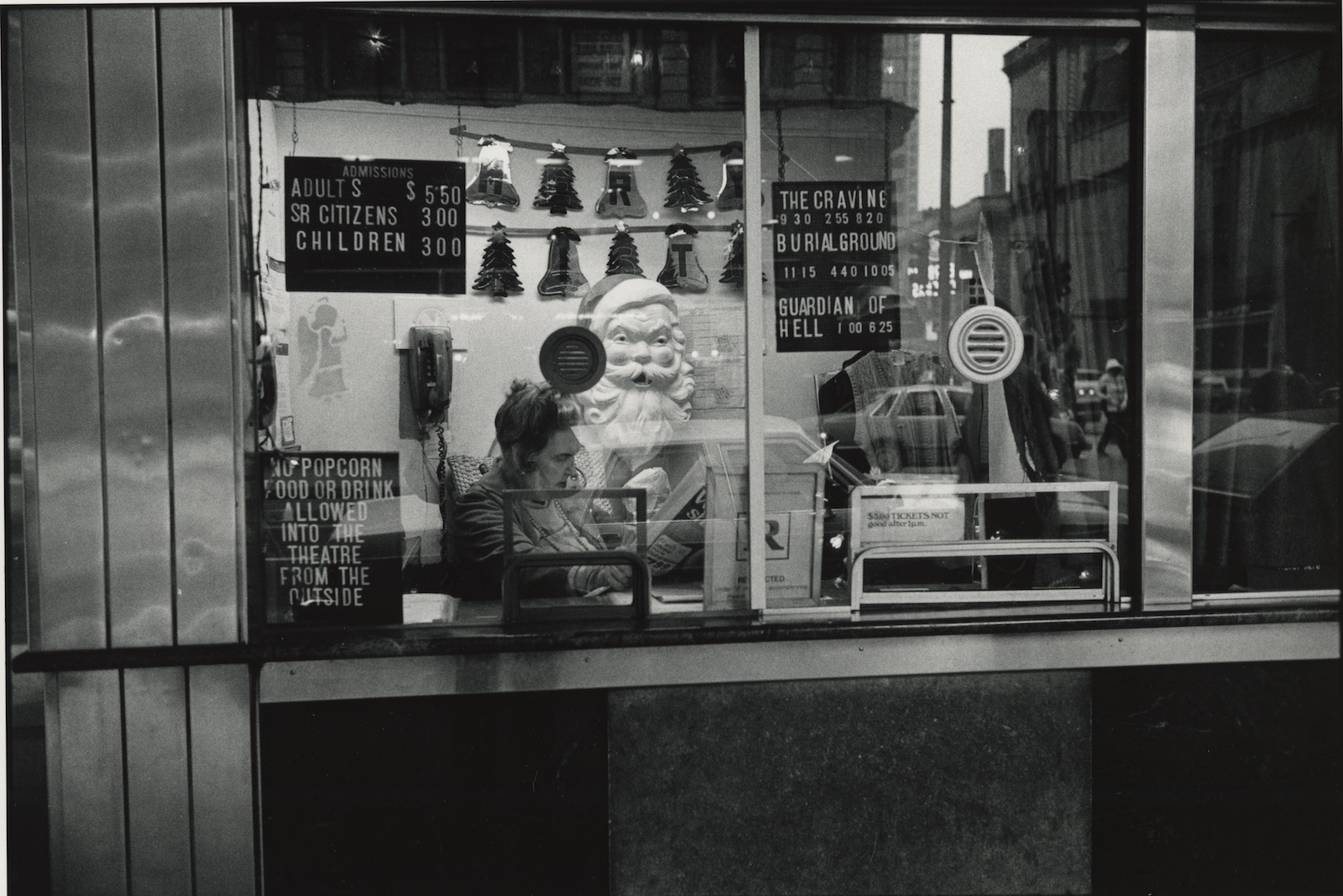

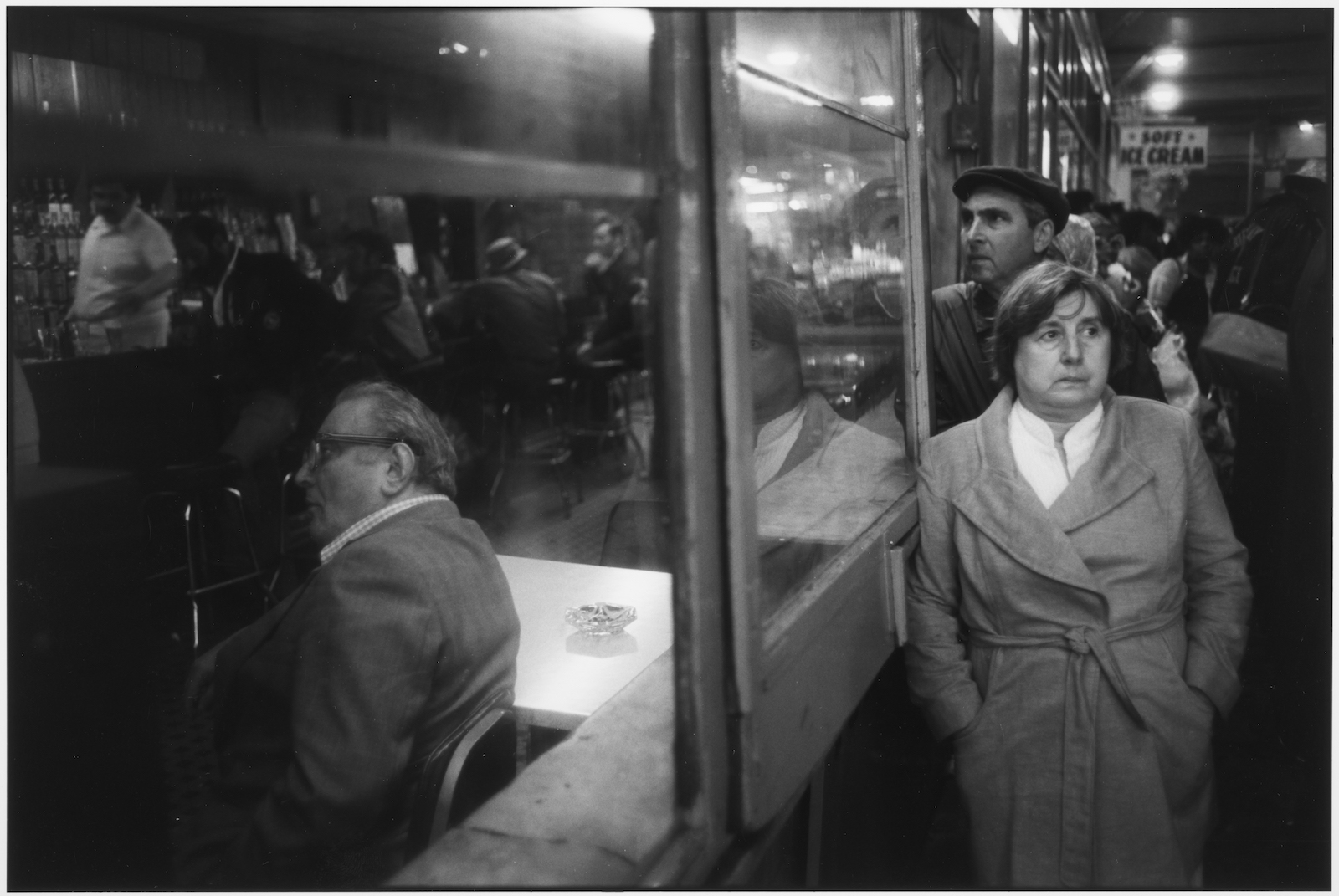

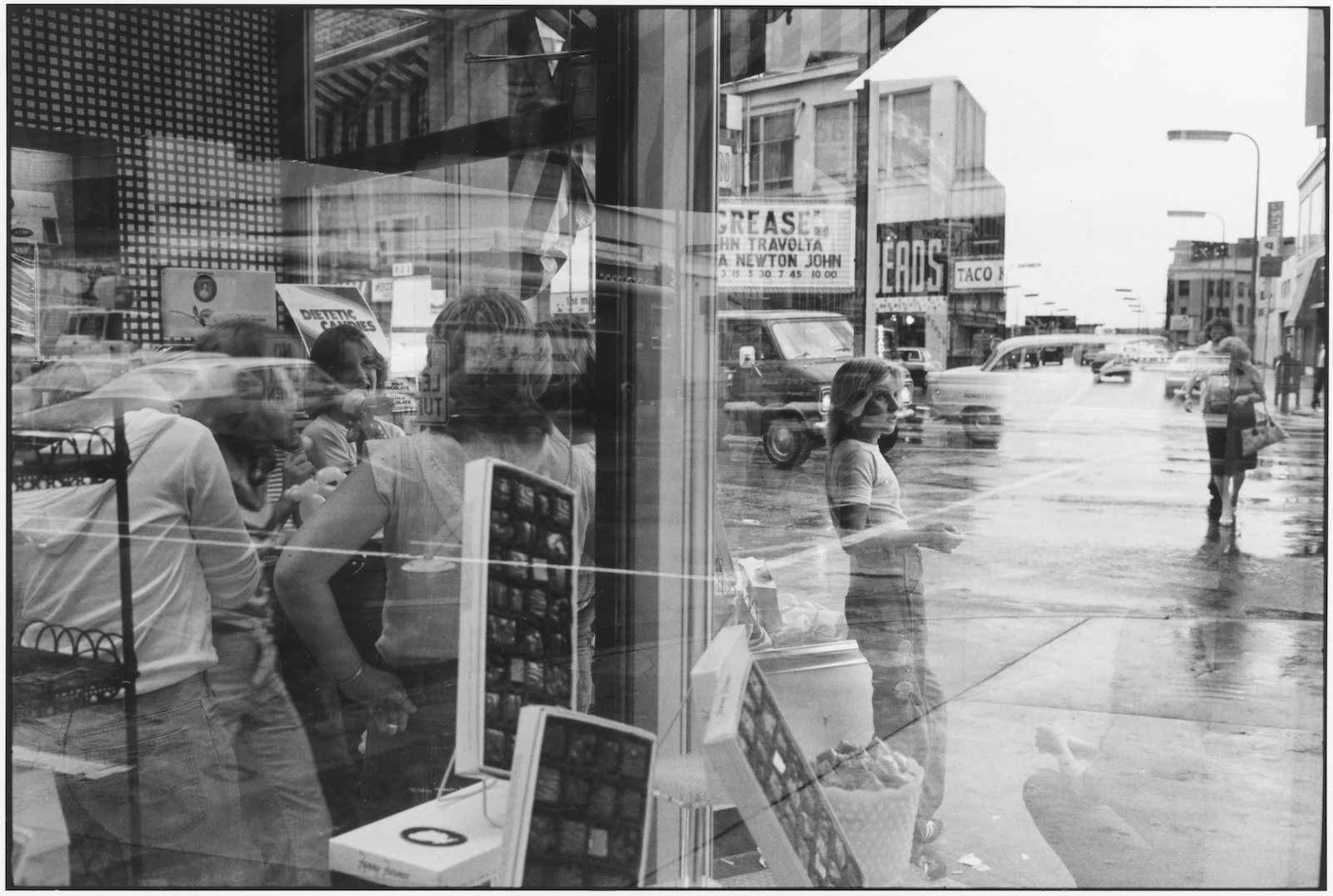

A stalwart Midwestern matron posing with her lawn mower on a tidy sidewalk. A gathering of animated adolescent girls glimpsed through the glare of a downtown candy shop's windows. A pensive man caught in a cigarette machine's mirror as he sits in a ray of sun at a diner counter. These are scenes any of us might encounter at any instant of our lives. While we might apprehend the beauty or poignancy of these fleeting moments, it takes extraordinary skill and reflexes to use a camera to transmute them into art. Minneapolis photographer Tom Arndt, author of these and thousands more frank, heartbreakingly real black-and-white images, is among a select few masters of street photography with the eye, instincts, and technical know-how to spin poetry from everyday sights.

Since the early 1970s, Arndt has dedicated himself to searching for telling images of people and the times and places they inhabit. Using the genre's classic tools, Kodak Tri-X film and a fast, unobtrusive Leica, he has roamed the streets of big cities and small towns in the United States, Europe, and Latin America in search of those elusive and evanescent instances where stories and pictures align. His work connects to an august tradition of humanist street photography?images concerned with life's universal themes. It extends the innovations of the genre's greats, past and present: Henri Cartier-Bresson's intricate instantaneity; Garry Winogrand's offhand timing and humor; Robert Frank's unvarnished take on the American scene. Yet Arndt's sensibility is wholly his own.

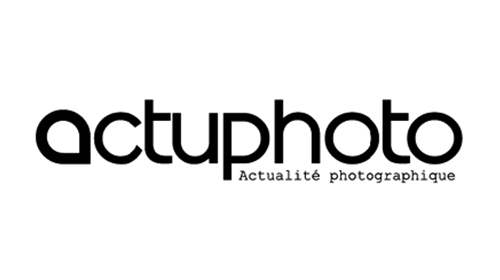

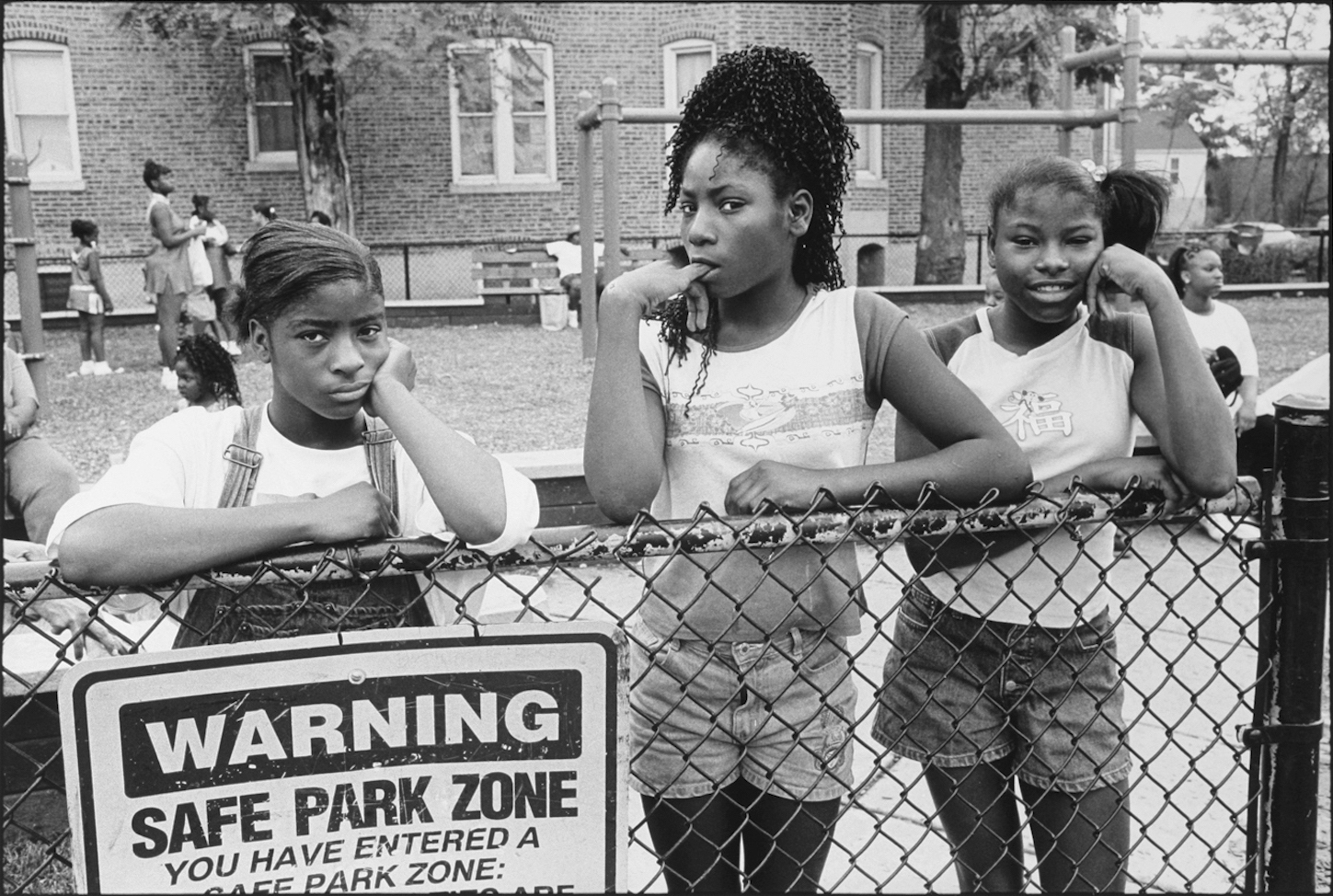

There is something more gentle and less brittle about Arndt's work than that of these predecessors and many of the genre's greats. He is less concerned with capturing Cartier-Bresson's "decisive moment" of compositional and symbolic perfection than stretching time a tiny bit to suggest its flow. Whether he's depicting a conversation, a trip, or even the act of waiting around, you feel Arndt's appreciation for the rare psychic state of absorption. Catching the quotidian reveries that occur in taverns, on busses, or on front steps is one of Arndt's specialties. His compositions are often casual, as if the photographer were part of the scene rather than a razor-eyed, detached observer. Most strikingly, though, his humanism has a different tenor than that of most street photographers who work candidly or without directly engaging their subjects. While Arndt makes many pictures that catch his subjects unaware, he just as often lets us see that his subjects see themselves being seen.

Arndt is never dispassionate. He has committed himself to depicting his fellow humans with care. "I'm interested in what it means to be alive. My subjects are people trying to get through today, and I'm with 'em," he says. "I want to make sure the people I photograph are fairly portrayed and in a respectful way." Poverty, loneliness, and the slog of it all are regular themes in his work, but the cynical "gotcha" edge that animates many street photographs is never present. As demonstrated by his images of spectators bunched together on bleachers at a small-town tractor pull in 2013, a man peering at a menu posted in a restaurant window in 1982, and an empty phone booth in a bar in St. Paul taken in 1971, the desire for connection is always a subtext.

In this sense, Arndt's nearest peers are Helen Levitt and Jerome Liebling, the latter of whom was his professor at the University of Minnesota in 1969 and 1970. Both Levitt and Liebling share his habit of turning photographic encounters into amicable mini-collaborations. Arndt also has their ability to engage people of different ages and races. One of the greatest compliments he ever received, Arndt says, was from an African-American television executive who told him that his photographs of Black Chicagoans were the first in which she couldn't tell whether the photographer was white. Arndt's photographs of groups of young people of color posing in Minneapolis and Chicago from the late 1990s and early 2000s (along with his pictures of beauty-shop windows, storefronts, and doorways) are images worthy of the great, socially engaged documentarians of the Depression era Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. They trace the changing demographics of regions long known for their white majorities.

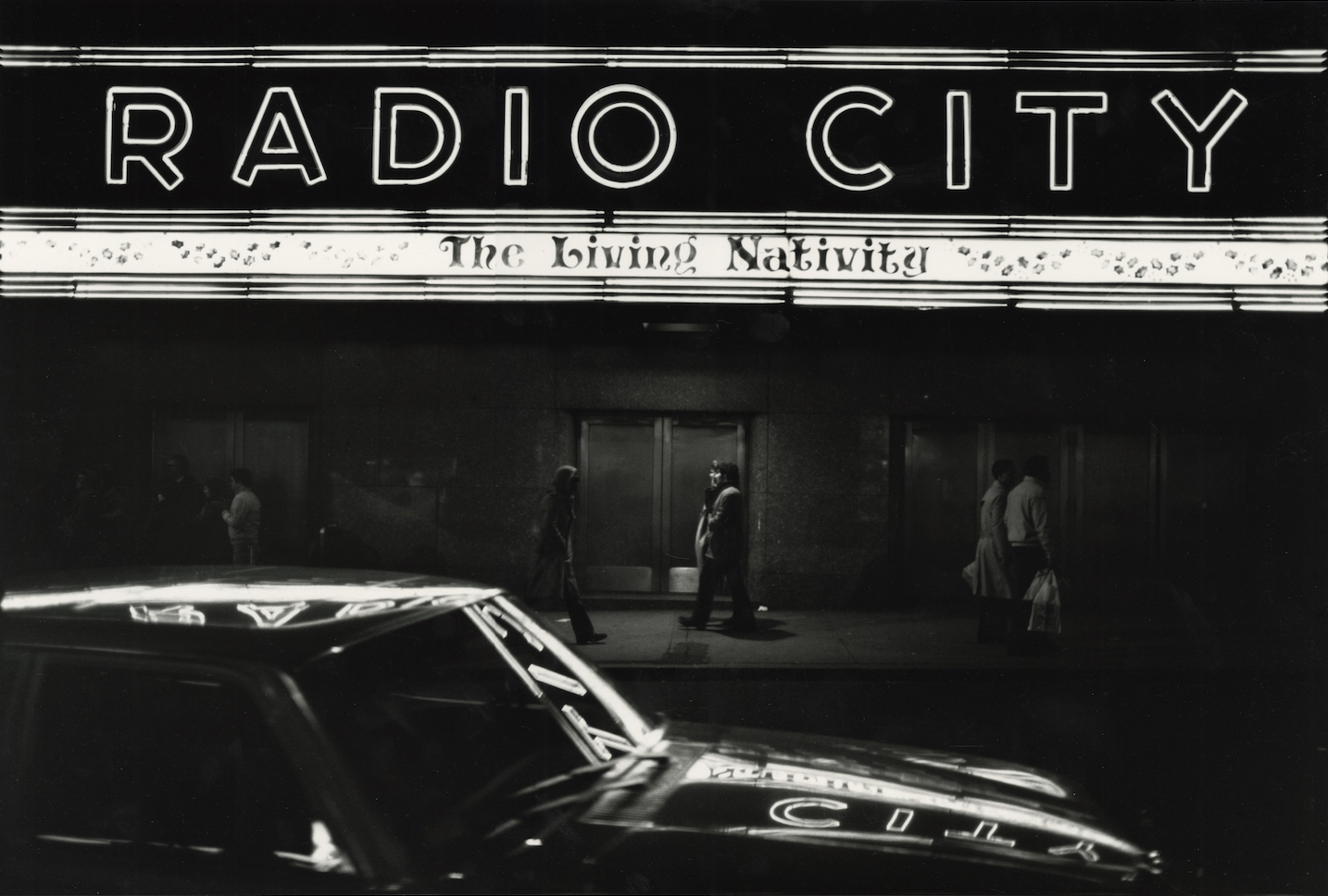

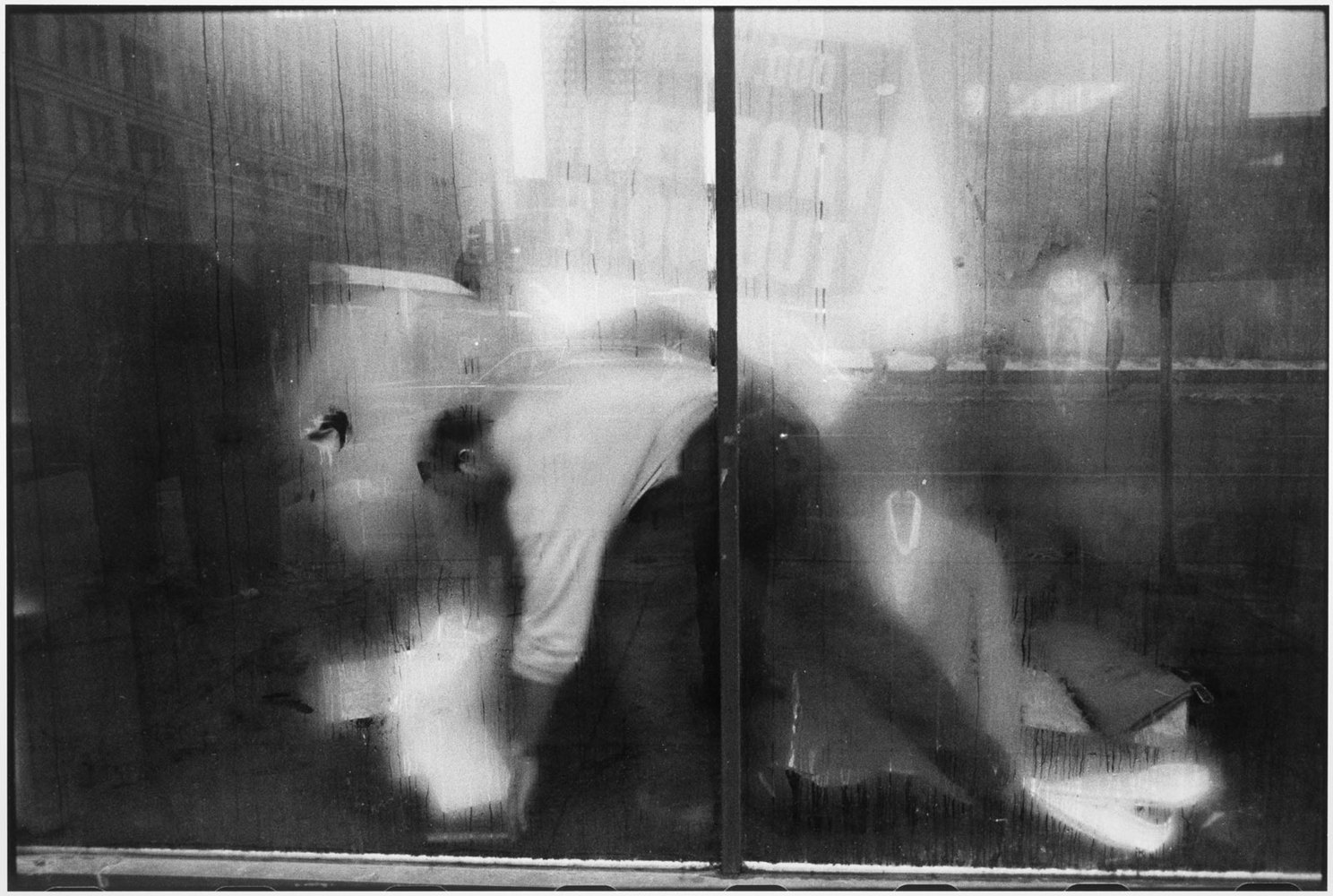

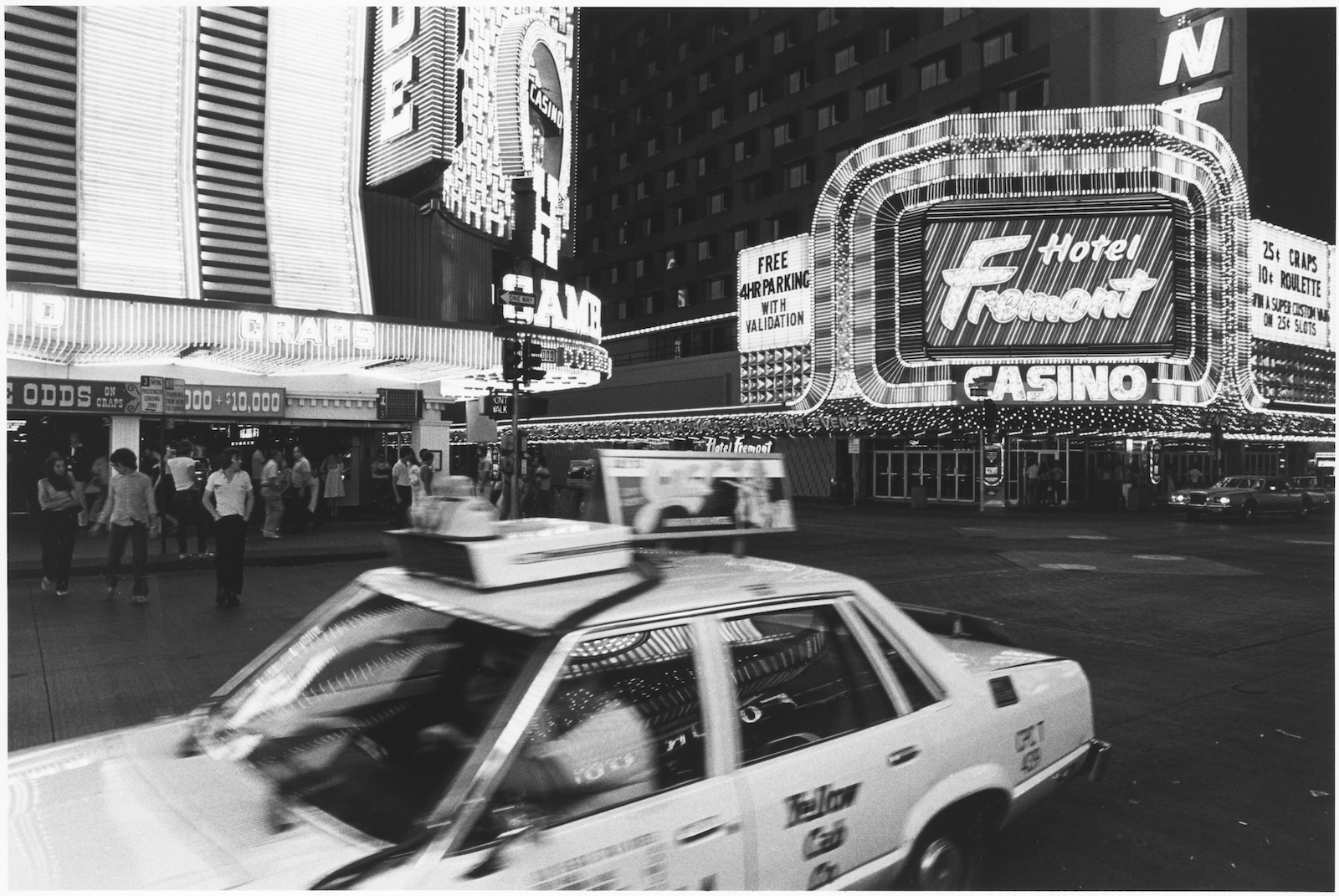

Looking at Arndt's photographs, one always gets the feeling he is at home in the world. His patience, curiosity, and passion for the tragicomedy of life shows in his images of three passengers in various states of self-possession on a bus traversing a neon-lit Las Vegas strip at night (Was it Umberto Eco's chronicle of American spectacles Travels in Hyperreality that, like the artist, lingered in a bar in St. Paul, Minnesota?); a man behind a fogged-up clothing store window in Chicago (the masculine plight is the subject of Arndt's 1994 book Men in America); and in a brilliant series of nocturnal shots of neighborhood 4th-of-July fireworks bacchanal in a New York neighborhood (is it Vietnam or Little Italy?). "The streets," Arndt has said, "are the common denominator of all of us. The streets contain our history. The streets are where the revolutions are made, where political statements are made, where the change is born."

Although his range is worldwide, Arndt is a true denizen of the Upper Midwest. Manhattan, that nirvana for street photographers where he has worked since the beginning of his career, has become "Disneyland" of late, he believes. Chicago, on the other hand, where he lived in worked for years, using the darkroom and compiling and extensive archive of his work at the city's Art Institute, still has a vibrant texture. The city's blunt charm shines through in his shots of a boy strutting with a cane and bowler hat, a Ukrainian couple posing in front of their brick apartment building, and a customer leaving with takeout from a restaurant advertising "soul by the pound."

Arndt's native state of Minnesota, however, is his most evergreen subject. This northern territory can be tough for a street photographer. Its long, cold winters and short, hot summers, constrain public, communal life. Additionally, as radio host and humorist Garrison Keillor, a close friend of Arndt, has so often remarked, its residents are not known for their expressive dress or behavior. But these mostly down-to-earth folks are Arndt's people, and he finds ways to reveal sides of their characters. His affection for and understanding of them shows through in picture after picture.

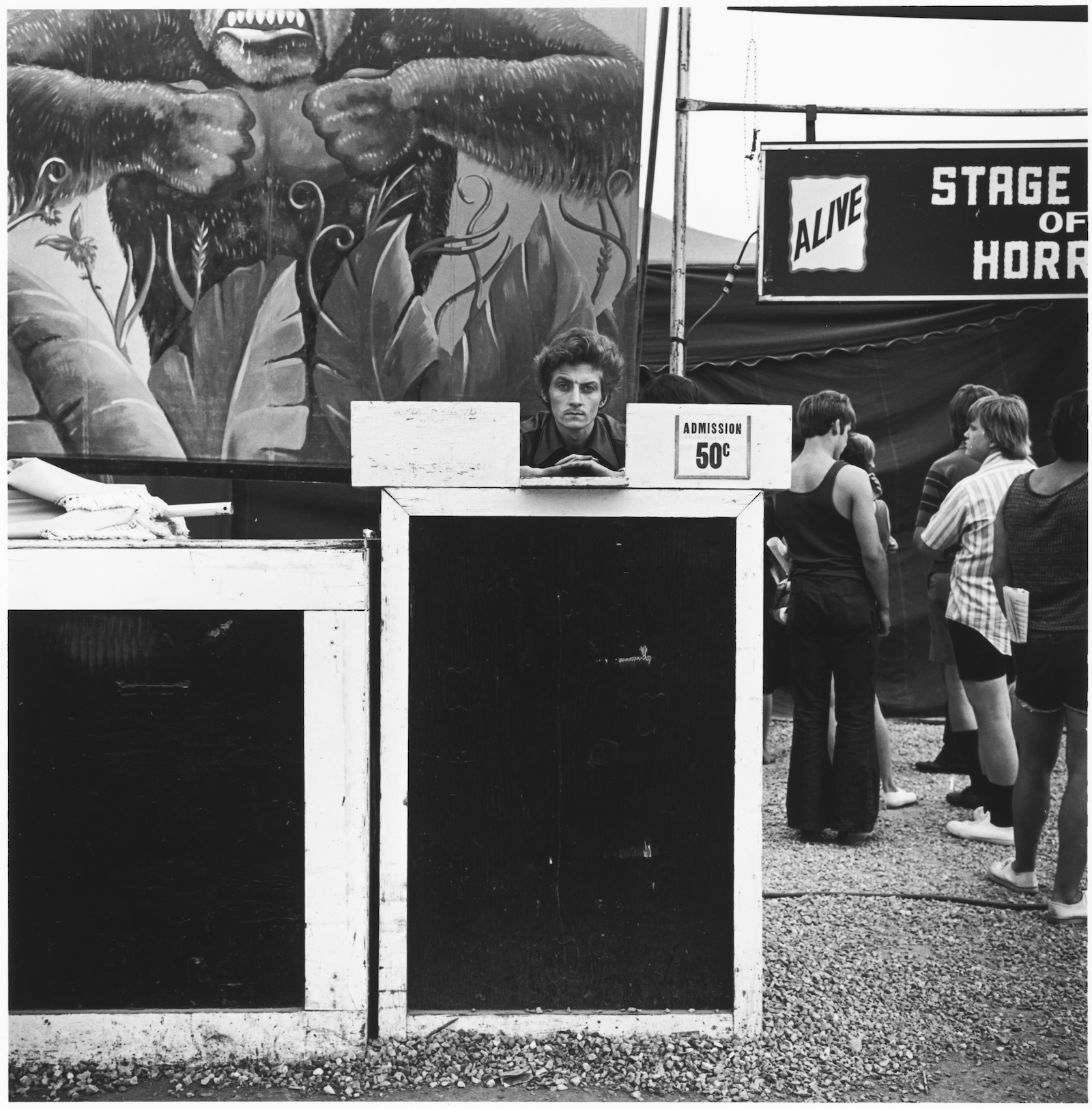

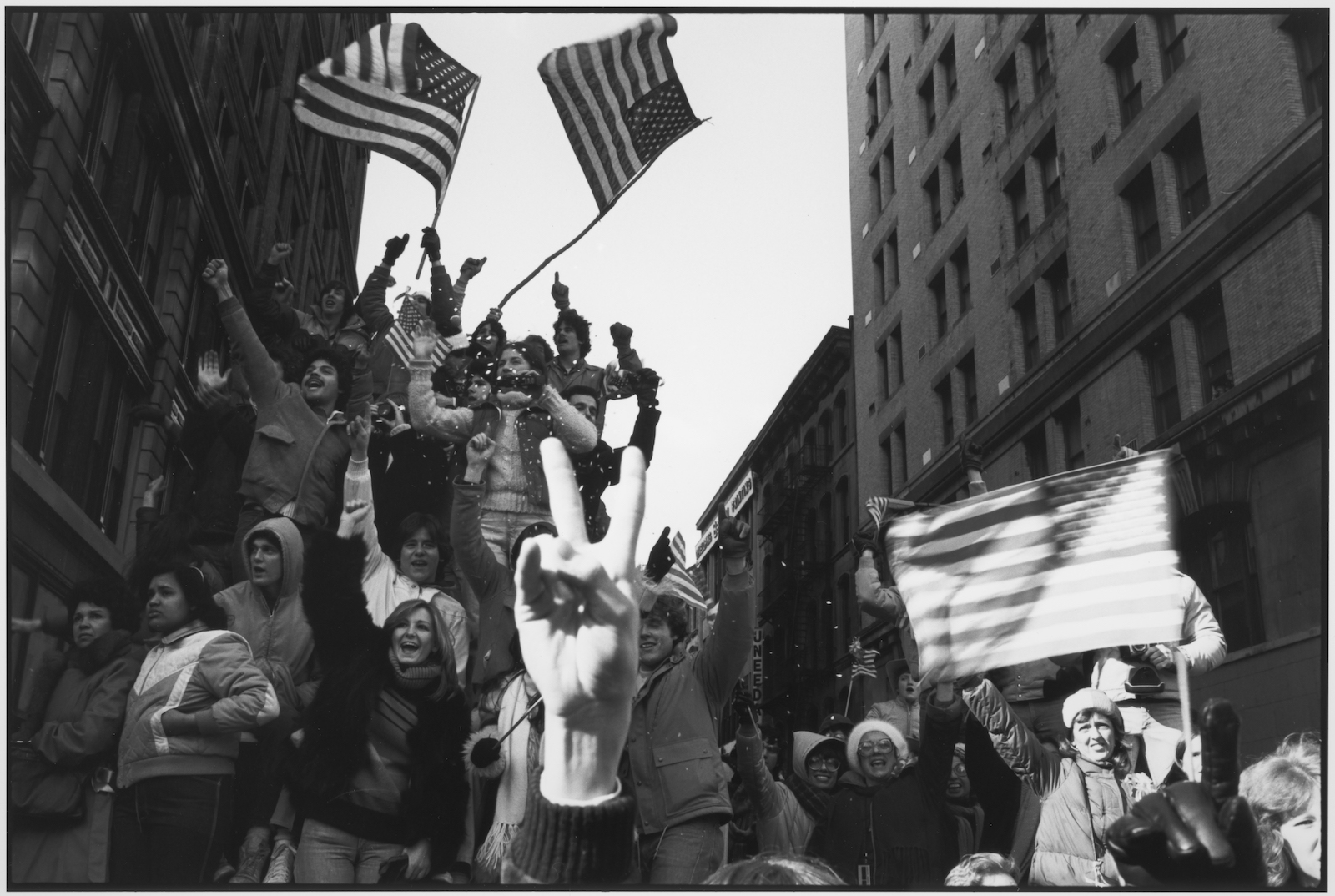

All corners of Minnesota provide subjects for Arndt: his Aunt Fud's bedroom and its beatific portrait of Jesus in the small town of Fergus Falls, guileless elderly trailer campers in the southern part of the state, and weatherbeaten pedestrians on Hennepin Avenue, Minneapolis's main thoroughfare. But in this exhibition's selection of photographs, Arndt's work from the state is most alive in photographs taken at state and county fairs, parades, and other communal celebrations. At these gatherings, where distractions abound and spirits are high, he can work quickly and blend into the rhythms of the event. A 1983 documentary video produced by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts shows Arndt in his element at the Minnesota State fair. He works fluidly, with palpable excitement and uses his trademark phrase "don't mind me" to disarm his subjects. In Two Women and the Flag, Payne Avenue, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1982, an image of two female spectators watching a color-guard parade from a second-story window, he succinctly captures America's distinctive brand of watchful patriotism. This and other flag-filled images in the exhibition call to mind Robert Frank's 1958 unromanticized study of folkways in the United States, The Americans. (Might Arndt be our own new, home-grown de Tocqueville?) Caramel Corn, Minnesota State Fair, St. Paul, Minnesota and Ticket Taker, Minnesota State Fair, St. Paul, Minnesota, two images of young people manning fairground stands taken in 1973, illustrate the peculiar mix of boredom and anticipation that is teenage life. And, perhaps the crescendo of the exhibition, the extraordinary photograph, Minnesota State Fair, 1976, which depicts a group of freshly-scrubbed young women gathering at dusk under an illuminated banner reading "American" induces a Pavlovian response in any good Midwestern boy?your author included?because it so perfectly summarizes the promise of a summer night in the Heartland. Of course, it's understandable why a state fair, with its agricultural competitions, nostalgic Americana, and fried food, has such appeal for an artist like Arndt. In a sense, it does what his photographs do: it miniaturizes the world and creates space for different views of ourselves.

Whether made at a Minnesota fair, a New Orleans bus stop, or on an empty road in Western Montana, Tom Arndt's photographs are an invaluable form of art. Plucked from the real world, his images break the engulfing experience of visual perception into crystalline fragments and grant us rare leverage on the incessant flow of time and consciousness. Like any carefully observed portrait or cityscape, they reveal everyday life's telling patterns and moods. As is typical of the genre, Arndt's street photographs leave the big questions unanswered: who are his subjects, where are they going, and what are they thinking? Yet his photographs of lives being lived distinguish themselves by their generous spirit. In their intimacy, sincerity, and openness, they convey the palpable sense that the photographer is right there with us on our journeys.

Toby Kamps

Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art The Menil Collection, Houston

Exhibitions

Paris Photo 2019

Group show

7 - 10 November 2019

Les coups de coeur de l'équipe

Group show

June 20 - July 27 2019

Paris Photo 2018

Group show

8 - 11 November 2018

AIPAD 2018

Group show

5 - 8 April 2018

Paris Photo 2017

Group show

9 - 12 November 2017

Black Chicago

Group show

October 28 2017 - January 13 2018

Paris Photo 2016

Group show

10 - 13 November 2016

Chicago Eyes

Raeburn Flerlage,

Vivian Maier

October 16 - November 27 2015

Photo London

Group show

21 - 24 May 2015

New York

Group show

March 20 - June 13 2015

Home

November 7 2014 - January 10 2015

News

Chicago intime / My Chicago

October 27 - December 23 2018

Where I live

May 25 - July 7 2017

L'ombre et l'angle

Berenice Abbott,

Luc Boegly,

Stéphane Couturier

7 - 29 April 2017

Chicago Eyes with Henri Peretz

Raeburn Flerlage,

Vivian Maier

October 18, 2015